|

|

Animated depiction of developing rip current from orthogonal (perpendicular) flow of water and waves. In this case, water converges at the beach and feeds back out through the gap in the sandbar. |

|

| What are Rip/Longshore Currents? | |

|

Rip Currents Rip currents can range from 10 to 20 feet wide to as large as 100 to 200 feet wide. The length of the rip current usually begins to diminish beyond the breaking waves, but can sometimes extend hundreds of feet beyond the surf zone. Rip currents can be found almost every day at many beaches, especially at low spots or breaks in the sandbars. They frequently occur near structures such as jetties and piers. Along the Lower Texas Gulf Coast, common rip current locations are at the South Padre Island/Boca Chica jetties, and at the Port Mansfield jetties. Rip current indicators include differences in water color, a break in the incoming wave pattern, a channel of churning and choppy water, or a line of foam, seaweed, or other debris moving steadily seaward. Often, these indicators will not be noticeable. Swimmers should always proceed with caution if planning to enter the surf, particularly near jetties and piers. On South Padre Island, rip currents become most dangerous during a long period swell from the east. These are most common in October and November, when the first broad high pressure systems of autumn can set up across the southeastern United States. These systems build a long period swell perpendicular to the shoreline, intensifying rip currents between sandbar breaks but especially along and just north of the Isla Blanca and Boca Chica jetties. The second most common period for rip currents is between June and September, when a weaker but persistent ridge of high pressure sets up from Bermuda through the southeastern United States. The ridge may combine with waves or cyclones moving from east to west through the deep tropics, enhancing easterly flow and building the long period swell. Summer rip currents are most dangerous, as hot temperatures on the beach draw more swimmers of all ability into the water. Moderate rip current mid summer days in past years have resulted in dozens of water rescues – per day! Longshore Currents Larger waves create faster longshore currents. The angle of wave approach when breaking also affects the speed of the current. Peak currents occur when the wave approaches from 45°. Higher or lower angles produce slower currents. Waves breaking parallel to the shoreline will have no longshore current generated by the wave angle. Like rip currents, longshore currents are subtle but can be seen or felt while standing in the surf zone. Longshore currents will always be present with rip currents as part of the nearshore circulation system. Large scale currents moving at slower speeds in the surf zone can also be generated from persistent moderate to strong winds as opposed to locally breaking waves. Longshore currents are particularly dangerous to beachgoers north of the Isla Blanca jetty, especially in the vicinity of the public beach access points from Andy Bowie Park northward. Deeper water, usually near or above the typical height of a person, between the sandbars can cause the longshore or rip currents to move swimmers along and away from the shore more efficiently. Longshore currents can also enhance the intensity of rip currents where they increase the feeder source in the vicinity of the barrier. |

|

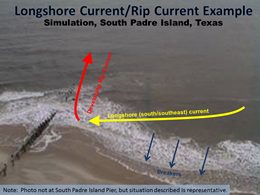

Simulation of current and wave activity along the south side of the Boca Chica jetty in persistent south/southeast longshore current. Breakers still occur at an angle to the coast; the strength of the current and angle of breakers increases the feeder source, and can intensify the neck and head of a rip current in the vicinity. |

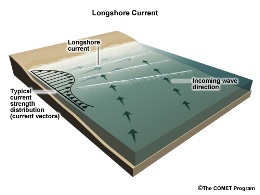

General depiction of longshore current. Current strength peaks in the middle of the surf zone, shown by arrows and curve at left of image. |

| Return to Index | |