|

2022 National Hydrologic Assessment

Released on March 17th, 2022

View the PDF version of the 2022 National Hydrologic Assessment

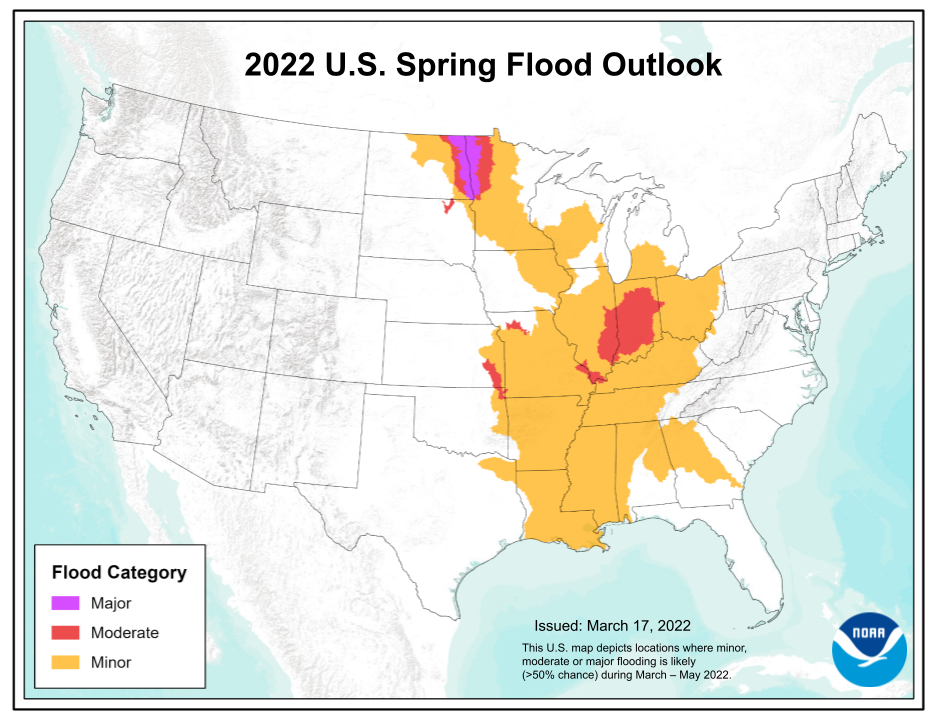

Figure 1: National Spring Flood Risk defined by risk of exceeding Minor, Moderate, and Major Flood Levels. Figure 1: National Spring Flood Risk defined by risk of exceeding Minor, Moderate, and Major Flood Levels.

Download the shapefile | Download the layer file (right click and save as) | Download the KMZ file

For an interactive look at the Spring Flood Outlook, please visit the 2022 Spring Flood Outlook Story Map Journal

Executive Summary

The 2022 National Hydrologic Assessment offers an analysis of flood risk, water supply, and ice break-up and jam flooding for spring 2022 based on late summer, fall, and winter precipitation, frost depth, soil saturation levels, snowpack, current streamflow, and projected spring weather. NOAA's network of 122 Weather Forecast Offices, 13 River Forecast Centers, National Water Center, and other national centers nationwide assess this risk, summarized here at the national scale.

This spring season, approximately 80 million people are at risk for flooding in their communities, with nearly 6 million at risk for moderate flooding and a half a million at risk for major flooding.

Late fall precipitation, along with above normal winter snowfall and below normal winter temperatures have led to an above normal risk of major flooding along the Red River of the North basin and moderate flooding along the James River in South Dakota. Above normal winter precipitation has led to ongoing minor flooding for portions of the Ohio River Basin, the mainstem Ohio River, and portions of the mainstem Lower Mississippi River. This wet pattern is expected to continue across these regions, with above normal precipitation predicted through early spring. As a result, there is an above normal risk of minor to isolated moderate flooding is predicted for the Ohio and Tennessee River Basins.

Current water supply forecasts in the western United States generally indicate below to much below normal water supply conditions due to dry fall and winter, coupled with ongoing widespread drought. Exceptions include portions of the northern Northwest, where near to slightly above normal water supply is forecast, driven by near to much above normal snowpack.

In Alaska, spring ice breakup and snowmelt flood potential is forecasted to be above normal for the majority of the state. The flood potential is expected to be well above normal for the Yukon, Tanana, Koyukuk, Kuskokwim and Susitna basins.

Based on the expected spring flood outlook, average hypoxia zones are expected for the Gulf of America and for the Chesapeake Bay.

Heavy, Convective Rainfall and Flooding

The information presented in this report focuses on spring flood potential, using evaluation methods analyzed on the timescale of weeks to months, not days or hours. Heavy rainfall at any time can lead to flooding, even in areas where the overall risk is considered low. Rainfall intensity and location can only be accurately forecast days in the future, therefore flood risk can change rapidly. Stay current with flood risk in your area with the latest official watches and warnings at weather.gov For detailed hydrologic conditions and forecasts, go to water.weather.gov.

NOAA’s Experimental Long Range River Flood Risk Assessment

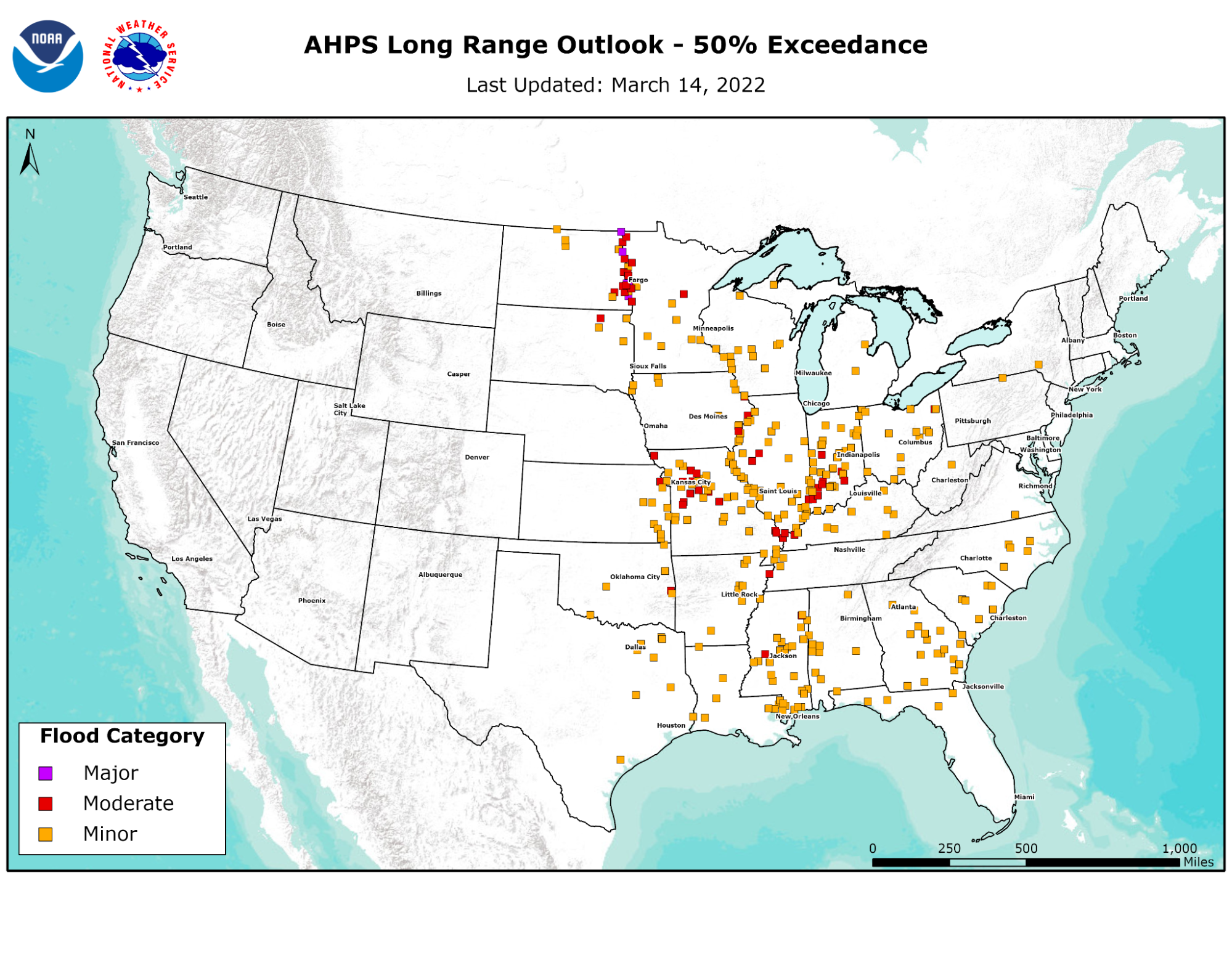

Figure 2: Greater than 50% chance of exceeding minor, moderate, and major river flood levels during Spring Figure 2: Greater than 50% chance of exceeding minor, moderate, and major river flood levels during Spring

At the request of national partners, including the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) continues its improved decision support services with the "Long Range River Flood Risk" web page available at https://water.weather.gov/ahps/long_range.php. Here, stakeholders can access a single, nationally consistent map depicting the 3-month risk of minor, moderate, and major river flooding as shown in Figure 2. This risk information is based on NOAA’s Ensemble Streamflow Prediction (ESP) forecasts which are generated for approximately 2,600 river and stream forecast locations across the nation. With this capability, stakeholders can quickly view flood risk predicted to affect their specific area of concern. The Long-Range River Flood Risk improves the value of the National Hydrologic Assessment by clearly and objectively communicating flood risk at the local level.

The sections below quantify river flood risk based on the river location having a 50% or more likelihood of exceeding minor, moderate, or major flood levels. The National Weather Service (NWS), in coordination with local officials, defines flood levels for each of its river forecast locations, based on the impact over a given area. The flood categories are defined as follows:

- Minor Flooding: Minimal or no property damage, but possibly some public threat (e.g., inundation of roads).

- Moderate Flooding: Some inundation of structures and roads near streams. Some evacuations of people and/or transfer of property to higher elevations.

- Major Flooding: Extensive inundation of structures and roads. Significant evacuations of people and/or transfer of property to higher elevations.

- Record Flooding: Flooding which equals or exceeds the highest stage or discharge observed at a given site during the period of record. The highest stage on record is not necessarily above the other three flood categories – it may be within any of them or even less than the lowest, particularly if the period of record is short (e.g., a few years).

Upper Mississippi River, the Red River of the North Basins, and the Great Lakes Region

The risk of spring snowmelt flooding is above normal across the Red River of the North basin and its tributaries with moderate to major flooding predicted, while the risk is generally near normal for much of the Upper Mississippi River Basin and the Great Lakes Region. Late fall rainfall reduced drought conditions over portions of the Red River of the North Basin and increased soil moisture content to normal and above normal levels before the winter freeze up. Colder than normal temperatures this winter increased frost depth to above normal throughout this region, allowing for moisture to remain stored within the soil and making the soil impervious to runoff from snowmelt. Combined with above normal snow water equivalent, as well as near normal streamflow, there is an increased threat of spring flooding.

A potential for minor flooding exists along portions Souris, Minnesota, and Wisconsin River basins. Minor to isolated moderate flooding is possible along portions of the Illinois and Upper Mississippi Rivers basins. Additionally, there is a risk of exceeding minor flooding along many of the rivers in the Great Lakes Region. Due to the below normal temperatures this winter, spring ice jams remain possible in areas of North Dakota and northern Minnesota.

Ohio, Cumberland, and Tennessee River Valleys

Minor flooding is currently occurring on portions of the Lower Ohio River as well as tributary basins through the region due to rainfall and snowmelt during February and early March. The potential for additional minor to moderate river flooding will be above normal this spring for much of the Ohio, Cumberland, and Tennessee River basins. Specifically, the potential for moderate flooding exists over portions of the Wabash River basin in Illinois and the White River Basin in Indiana. Isolated major flooding cannot be ruled out in the Ohio Valley this spring. The above normal precipitation over February into early March is a result of a typical La Niña pattern, and it is predicted to continue through the remainder of at least May. Typically, convective storms are the main drivers of spring flooding in the area.

Missouri River Basin

Overall, the potential for spring flooding in the Missouri River Basin is below normal. However, moderate flooding over portions of the James River in South Dakota is possible due to spring snowmelt runoff. The Lower Missouri River tributaries in Missouri have the potential for minor to moderate spring flooding, with the possibility of minor flooding along the Lower Missouri River mainstem in Missouri. Flooding in this portion of the basin is mainly driven by springtime thunderstorm activity. Mountain snowpack in the upper portion of the basin is generally below normal; therefore, widespread significant flooding in the mountainous west of the basin is not likely due to mountain snowmelt alone.

An overall reduced risk is mainly driven by dry conditions that have been dominant over most of the Missouri Basin over the past 12 months or more, with drought firmly entrenched over much of the basin. Temperatures have remained above normal through the winter across most of the basin, which when combined with the dry conditions, has allowed for a reduced threat of ice jam and breakup flooding driven by snowmelt runoff.

Arkansas and Red River Basins

The potential for spring flooding is near normal across most of the Arkansas and Red River basins. Flood events in the Arkansas River headwaters are driven by rapid snowpack runoff or isolated, high-intensity rainfall events, whereas in the remainder of the basin, the spring flood potential in this region is driven by convective rainfall. Snowpack in the Rocky Mountain headwater region of the Arkansas River basin is generally below normal. Widespread drought is currently impacting 85% of the area except for basins in eastern Oklahoma, southeastern Kansas, southwestern Missouri, and central Arkansas. As such, streamflows are generally experiencing normal to below normal flows.

Moderate flooding may be possible over the lower Neosho River in Kansas and Oklahoma. Minor flooding may be possible in the Poteau and Illinois River basins in eastern Oklahoma. Ultimately the spring flood potential in this region is driven by convective rainfall.

Lower Mississippi River Basin and its Tributaries

Normal spring flood potential with minor to isolated moderate flooding exists along the mainstem Lower Mississippi River this spring with an above normal flood potential on tributary basins in southern Missouri, extreme southwestern Illinois, and western Kentucky. This is based on the current near to above normal soil moisture and streamflows, along with predicted precipitation patterns. Meanwhile, near normal spring flood potential exists on the tributaries of the Lower Mississippi River in southern Arkansas, Mississippi, and Louisiana with minor flooding ongoing over this area. Drought is prevalent over the region due to below normal precipitation through the winter.

Texas and Southwest Louisiana

Below normal spring flood potential exists over Texas and southwest Louisiana. Widespread drought persists and has resulted in normal to below normal soil moisture and streamflows across the region, except in portions of south Texas, which received near normal winter precipitation. In this area, soil moisture is near normal, but streamflows remain below normal.

Southeastern United States

Minor flooding is possible over portions of the Oconee and Coosa River basins in Georgia and Alabama as well as the Tombigbee River in northeast Mississippi and western Alabama this spring. While recent rainfall has led to ongoing and minor flooding forecasts, elsewhere, normal spring flood potential exists over the southeastern United States. Winter precipitation has been below normal for most of the region with the exception of central through northern Alabama and northern Georgia. Soil moisture values are below normal over the coastal areas but increase to near normal inland to above normal over portions of the Southern Appalachians into the Southern Piedmont. Streamflow values are generally normal and follow soil moisture trends with areas of above to much above normal streamflows exist in areas with above normal soil moisture.

Northeast

Normal river flood potential exists across the Northeast this spring. The potential for flooding due to ice jams is normal, except in Maine where the potential in western and northern Maine is currently near normal but will increase to above normal during late March based on temperature and precipitation forecasts. This will be a result of predicted warming temperatures along with runoff from snowmelt and precipitation. Elsewhere across the region, the potential for flooding relating to ice jams is either below normal or has passed for the season.

Winter precipitation has ranged from near normal across western portions of New York and coastal portions of southern New England to below normal elsewhere. Most rivers across the northern half of New England have near normal ice coverage as of mid-March. Ice-free rivers are experiencing near to above normal flows. Soil moisture levels remain wet in areas of New York and New England that have experienced recent melt.

Middle Atlantic Region: Virginia, Maryland, Washington D.C., Pennsylvania, Delaware, and south-central New York

Normal river flood potential exists this spring across the Mid-Atlantic region. Winter precipitation has been below normal for much of the region, which has led to normal to below normal streamflows especially across the Chesapeake, Delaware, and Hudson River basins. Soil moisture values remain near normal in snow-free basins from southeastern Pennsylvania and New Jersey south through eastern Virginia. Minor river flooding across northern portions of the Susquehanna and Delaware River basins cannot be completely ruled out; however, with a lack of snowpack, observed spring flooding should remain within the normal range.

Western U.S.

Mid-March is usually too early to determine spring flooding potential across the western United States due to snowmelt, since snowpacks at higher elevations may continue to build over the next several months.

Water Supply

Western U.S.

Water supply forecasts are produced by the River Forecast Centers in the western United States. Forecasts are impacted by current and antecedent hydrologic conditions including snowpack, soil moisture, weather forecasts, and climate information. As these conditions change, especially over the next couple months, forecasts will be updated to reflect these changes at the Western Water Supply Forecasts For detailed information on current drought conditions, please see the US Drought Monitor website. Drought outlook information can be found on the NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center’s website.

Northwest

The northern portions of the Northwest are forecast to experience normal to above normal water supply through September due to overall above normal snowpack and near normal precipitation. Southern portions of the region are forecast to experience below normal water supply through the remainder of the water year resulting from below normal snowpack and precipitation combined with ongoing drought. Mountain snowpack is generally near normal from the central through northern Cascades in Washington and Oregon into northern Idaho and western Montana. From southwestern and eastern Oregon into southern Idaho and southwestern Montana, snowpack is below normal. Water supply forecasts for April through September runoff volume across the Northwest are summarized below:

- Upper Columbia basin: 85 to 120% of normal

- Snake River basin: 55 to 90% of normal

- Columbia River at The Dalles (a good index of conditions across the Columbia Basin): 95% of normal

- Northeast Oregon basins: 65 to 85% of normal

- Northwest Oregon basins: 80 to 90% of normal

- Southern and central Oregon basins: 15 to 65% of normal

- Northwestern Washington basins: 90 to 100% of normal

- Southwestern Washington basins: 80 to 95% of normal

- Eastern Washington, northern Idaho, and western Montana basins: 85 to 105% of normal

California

Below to much below normal water supply runoff volumes are forecast in California for April through July this year. Mountain snowpack is below normal throughout the state, with northern areas at 55% of normal, the central Sierra Mountains at 65% of normal, and the southern Sierra Mountains at 60% of normal. A multi-year, statewide meteorological drought continues. Precipitation totals since the beginning of the water year are 25% to 75% of normal across northern and southern California. Across central California, precipitation has been near normal. Precipitation outlooks for the next six months suggest a continuance of the overall drier than normal conditions statewide. Runoff volumes are forecast for April through July throughout the state as summarized below:

- Lower Klamath River Basin: 25 to 35% of normal

- Sacramento River Basin: 45 to 55% of normal

- San Joaquin River Basin: 30 to 60% of normal

- Northern California Coast: 25 to 60% of normal

Nevada

Below to much below normal water supply runoff volumes are forecast for April through July in Nevada due to below normal snowpack. Snowpack across the state ranges from 70 to 80% of normal along the lee side of the Sierra Nevada to 50 to 70% of normal in the higher elevations across central and eastern Nevada, including the Ruby Mountains. Entering the spring snowmelt season, below normal streamflows continue all basins in the presence of the ongoing statewide, long-term drought. The April through September runoff forecasts in Nevada are as follows:

- Rivers and streams of the eastern Sierra: 35 to 45% of normal

- Humboldt Basin: 5 to 35% of normal

Colorado River and Great Basin

Below normal water supply runoff volumes are expected across the region. Water year precipitation to date has been below normal, especially from the Four Corners south into southern Arizona and southeastern New Mexico. Ongoing drought conditions combined with successive dry fall seasons have led to drier than normal soil conditions entering spring across the northern Colorado River Basin. Broadly, snow water equivalent is below normal as well, ranging from 60 to 100% of normal. The April through July water supply forecasts for the Upper Colorado River Basin are listed below:

- Yampa and White Basin: 70 to 95% of normal

- Upper Colorado Mainstem: 70 to 95% of normal

- Gunnison Basin: 55 to 105% of normal

- Upper Green Basin: 45 to 75% of normal

- Dolores and San Miguel Basin: 60 to 70% of normal

- San Juan Basin: 70 to 85% of normal

Unregulated seasonal inflow forecasts between April and July for some of the major reservoirs in the Upper Colorado River Basin include the following:

- Flaming Gorge: 55% of normal

- Blue Mesa Reservoir: 90% of normal

- McPhee Reservoir: 65% of normal

- Navajo Reservoir: 70% of normal

- Lake Powell: 70% of normal

Snow water equivalent generally ranges from 70 to 90% of normal across the eastern Great Basin into north central Arizona but decreases to 40 to 60% of normal moving southeast along the Mogollon Rim. The April through July water supply forecasts for the eastern Great Basin and the January through May forecasts for the Lower Colorado River basins, which includes the January through June water supply forecast for the Little Colorado basin, are listed below:

- Eastern Great Basin

- Bear: 35 to 80% of normal

- Weber: 35 to 75% of normal

- Six Creeks: 50 to 85% of normal

- Provo/Utah Lake: 55 to 80% of normal

- Virgin: 55 to 60% of normal

- Sevier: 65 to 85% of normal

- Lower Colorado River Basin

- Little Colorado and Upper Gila: 15 to 25% of normal

- Salt: 10 to 25% of normal

- Verde: 25% of normal

Water Resources East of the Rockies

Seasonal temperature outlooks favor a chance for overall warmer than normal conditions across the eastern Rockies and Great Plains into the eastern states through the spring. Precipitation outlooks suggest normal to below normal conditions are more likely to occur except across the Ohio River Basin and Great Lakes states where the chances for above normal precipitation exist. Across the eastern Rockies into the Southern Great Plains, ongoing drier than normal conditions through the winter, along with potential drier than normal conditions, is expected to lead to drought persistence and expansion.

Upper Missouri River Basin

Below normal water supply runoff volumes are forecast across the Upper Missouri River Basin through September due to a combination of below normal snowpack and below normal soil moisture resulting from ongoing drought conditions which are predicted to persist through the spring. The April through September water supply runoff forecasts for the Upper Missouri River Basin are listed below:

- Upper Missouri River Basin

- St. Mary River: 50 to 65% of normal

- Upper Missouri Basin above Fort Peck, Montana: 60 to 70% of normal

- Yellowstone Basin

- Yellowstone River above Sidney, Montana: 55 to 85% of normal

- Tongue Basin: 60% of normal

- Powder River: 45 to 50% of normal

- Platte Basin

- North Platte River at Seminoe Reservoir: 110% of normal

- South Platte Basin at South Platte: 65% of normal

- Remainder of the South Platte Basin: 55 to 115% of normal

Upper Arkansas River Basin

Normal to below normal water supply runoff volumes are forecast across the headwaters of the Upper Arkansas River Basin due to below normal winter precipitation. Ongoing, widespread drought is predicted to persist across the area through spring. With increased chances for normal to below normal precipitation predicted to continue through the spring and summer, little improvement is expected. The April through September water supply runoff forecasts for the Upper Arkansas River Basin are listed below:

- Arkansas River at Salida: 65% of normal

- Arkansas River above Pueblo Reservoir: 72% of normal

- Cucharas River near La Veta: 60% of normal

- Huerfano River near Redwing: 60% of normal

- Purgatoire River at Trinidad: 40% of normal

Upper Rio Grande Basin

Below normal water supply runoff volumes are forecast for the Upper Rio Grande Basin headwaters. Snowpack, streamflows, and soil moisture conditions remain below normal amid the ongoing, widespread drought which is predicted to persist through the spring. Selected seasonal water supply forecasts from April through September are listed below:

- Rio Grande Headwaters: 45 to 60% of normal

- Pecos River near Santa Rosa: 60% of normal

Northeast

No widespread water supply issues are predicted over the Northeast this spring. However, localized water supply issues may develop across northern portions of New York, Vermont, and New Hampshire as well as western Maine due to dry antecedent conditions. Reservoir and groundwater levels are generally near to above normal across the region except in portions of Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine that are impacted by abnormally dry and drought conditions. Above normal precipitation in February, along with early snowmelt, has provided reservoirs and streams with recharge; hence, no widespread water supply shortage is predicted this spring.

Mid-Atlantic

Water supply shortages are not predicted this spring in most locations. Abnormally dry to moderate drought conditions persist across portions of the Catskill region of New York, central through eastern Pennsylvania, northwest and southern New Jersey, and much of Virginia. Reservoir storage is near normal across the region (including the Delaware River Basin that supplies New York City water) except in southern areas where below normal reservoir levels are being observed. With near to above normal precipitation predicted over the next few months, only southeastern areas may develop potential water supply shortages.

Alaska Spring Ice Breakup Outlook

The Alaska spring ice breakup and snowmelt flood potential is forecasted to be above normal for the majority of the state. Specifically, the Yukon, Tanana, Koyukuk, Kuskokwim and Susitna basins are above normal while the Copper Basin and North Slope are near normal. This outlook is based on observed snowpack, ice thickness reports, and seasonal temperature outlooks. It is important to remember that while Alaska has experienced mostly mild winters for the past decade, “normal” is defined over a longer period and normal flood potential may be higher than in recent memory.

River Ice

March ice thickness data are available for a limited number of observing sites in Alaska. Late February and early March measurements indicate that ice thickness is near normal across the state with an exception being at the Yukon River near Galena, which is below normal as well as reports of above normal ice thickness along the middle Kuskokwim River due to a mid winter breakup.

Cumulative freezing degree days (FDD), which can serve as an indicator of ice thickness, are generally above normal statewide from a marginally colder than normal winter. FDD are 150 to 200% of normal for the coastal sites along the Gulf of Alaska (Sitka to Homer); 90 to 110% of normal for Southcentral, the Interior, and the North Slope; and 110 to 130% of normal for the West Coast.

Snowpack

Analysis of the March 1st snowpack by the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) indicates an above normal snowpack for the majority of the state. The snowpack for the Upper Yukon (largely in Canada) is well above normal, with the 34 sites within this basin reporting 160% of normal. Of these 34 sites, 16 are reporting record maximums. The Central Yukon Basin, which includes Eagle, Circle and Fort Yukon, is reporting 190% of normal from a massively snowy December and higher than normal accumulation in February. The Tanana Basin, which includes Fairbanks and Delta Junction, is reporting 220% of normal, with 8 of 28 stations reporting record maximums, and all sites reporting greater than 120% of normal. The Koyukuk Basin is estimated to be at 150% of normal with two sites reporting the highest snow water equivalent in the 16-year record. The Lower Yukon Basin, which includes the villages of Tanana, Ruby, Galena, and Anvik, is estimated to be at 150% of normal snowpack.

The Kuskokwim Basin in southwest Alaska has only three reporting sites. Telaquana Lake, in the upper basin, is reporting 6 inches of snow water equivalent, slightly less than the 6.5 inches reported in March 2021. McGrath snowpack is estimated to be 180% of normal. The Lower Kuskokwim Basin received copious precipitation in February, but not all of it as snow.

For the Arctic, the four stations along the Dalton Highway are reporting near normal snowpack.

In Southcentral Alaska, the Copper Basin has a varied snowpack. It is mostly above normal (150 to200% of normal) for the northern part of the basin, and below normal for the southern portion, near Thompson Pass. The Matanuska and Susitna basins are reporting well above normal snowpack with a basin approximation of 145% of normal. Stations in the Kenai Basin are reporting a range of values, with the inland sites reporting slightly below normal snow water equivalent, with the highest snowpacks reported at the southern extent of the basin. The basin-wide snowpack can be approximated at 115% of normal.

Climate Outlook

The most important factor determining the severity of ice breakup remains the weather during April and May. Dynamic breakups with a high potential for ice jam flooding typically require cooler than normal temperatures for most of April followed by an abrupt transition to warm, summer-like temperatures in late April to early May.

NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center outlook for March suggests an increased chance of above normal temperatures for most of Southcentral, Western and Northern Alaska. The Copper Basin and Eastern Alaska Range have equal chances for above and below normal temperatures and Southeast Alaska has increased chances for below normal temperatures. The longer, 3-month outlook, which includes April, May, and June, indicates equal chances for above and below normal temperatures for most of the state, but an increased chance of below normal temperatures for Southeast and eastern Southcentral Alaska.

Spring Flood Outlook and Implications for Gulf of America and Chesapeake Bay Hypoxia

In the northern Gulf of America, a large area of low-oxygen forms in the bottom waters during the summer months, often reaching in excess of 5,000 square miles. This area of low-oxygen, otherwise known as the “dead zone”, is strongly influenced by precipitation patterns in the Mississippi-Atchafalaya River Basin (MARB), which drains over 41% of the contiguous United States. Changes in precipitation influence river discharges into the Gulf, which carry the majority of nutrients fueling the annual dead zone, so examining spring flood risk in the basin can provide a useful indicator of the possible size of the dead zone during the summer.

The predicted spring flood risk across the MARB will likely lead to average or normal hypoxic conditions in the northern Gulf of America this summer. Large portions of the basin are not predicted to have an elevated flood risk or having near normal risk of minor flooding this spring. Absent major flooding, normal springtime discharges of nutrients and freshwater from the Mississippi River are predicted.

In the Chesapeake Bay, recurring summer hypoxia has also been linked to nutrient loading and river discharge, especially from the Susquehanna and Potomac rivers. The spring flood outlook for these basins does not indicate a risk of flooding. As a result, an average hypoxia zone for the Chesapeake Bay under typical summer conditions is expected.

Flood conditions, should they occur in the Mississippi-Atchafalaya, Susquehanna, and Potomac rivers, may lead to higher than normal springtime discharges and promote formation of a larger hypoxia area. This cause and effect relationship can be confounded by weather events, such as tropical storms and hurricanes, which can locally disrupt hypoxia formation and maintenance, like what has happened in previous years in the Gulf of America.

The spring flood outlook provides an important first look at some of the major drivers influencing summer hypoxia in the Gulf of America and Chesapeake Bay. In early June, measured river discharge amounts and corresponding nutrient concentrations will be available from the U.S. Geological Survey. This information will be used by NOAA and others to release annual dead zone forecasts for the Gulf of America and Chesapeake Bay. In the summer, the dead zone sizes will be measured and compared against the predictions. Hypoxia forecast models will evaluate the size of the dead zone based on causative factors such as watershed nutrient loading and deliver this critical information to the Gulf of America/Mississippi River Watershed Nutrient Task Force and Chesapeake Bay Program to assess the effectiveness of watershed nutrient reduction efforts to reduce the size of their respective dead zones. The National Weather Service and Ocean Service continue to work with States to develop new tools to forecast runoff risk which help limit nutrient runoff to the Gulf of America, Chesapeake Bay, Great Lakes and other regions by identifying the optimal times for fertilizer application within these watersheds.

NOAA’s Role in Flood Awareness and Public Safety

Floods kill an average of 90 people each year in the US. The majority of these cases could have been easily prevented by staying informed of the flood threat and following the direction of local emergency management officials.

To help people and communities prepare, NOAA offers the following flood safety tips:

NOAA's National Weather Service is the primary source of weather data, forecasts and warnings for the United States and its territories. It operates the most advanced weather and flood warning and forecast system in the world, helping to protect lives and property and enhance the national economy. Visit us online or on Facebook Twitter.

NOAA's mission is to understand and predict changes in the Earth's environment, from the depths of the ocean to the surface of the sun, and to conserve and manage our coastal and marine resources. Visit us online or on Facebook and Twitter.

About This Product

The National Hydrologic Assessment is a report issued each spring by the NWS that provides an outlook on U.S. spring flood potential, river ice jam flood potential, and water supply. Analysis of flood risk integrates late summer, fall, and winter precipitation, frost depth, soil saturation levels, streamflow, snowpack, temperatures and rate of snowmelt. A network of 122 Weather Forecast Offices and 13 River Forecast Centers nationwide assess the risk summarized here at the national scale. The National Hydrologic Assessment depicts flood risk over large areas, and is not intended to be used for any specific location. Moreover, this assessment displays river and overland flood threat on the scale of weeks or months. Flash flooding or debris flow, which accounts for the majority of flood deaths, is a different phenomenon associated with weather patterns that are only predictable days in advance. To stay current on flood risk in your area, go to water.weather.gov for the latest local forecasts, warnings, and weather information 24 hours a day.

|