On this page you learn what types of flooding are typical in Alaska and how to you protect yourself, your family and your home. You will also find out more about significant Alaska floods. Finally, you'll find links to NWS offices that provide forecast and safety information for Alaska, as well as links to our partners who play a significant role in keeping you safe.

|

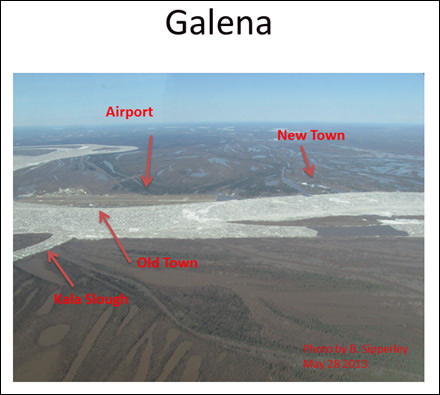

| May 28, 2003 looking north, showing the ice-clogged Yukon River. The dike-protected airport is clearly visible |

Photo courtesy of Alaska Division of Community & Regional Affairs |

|

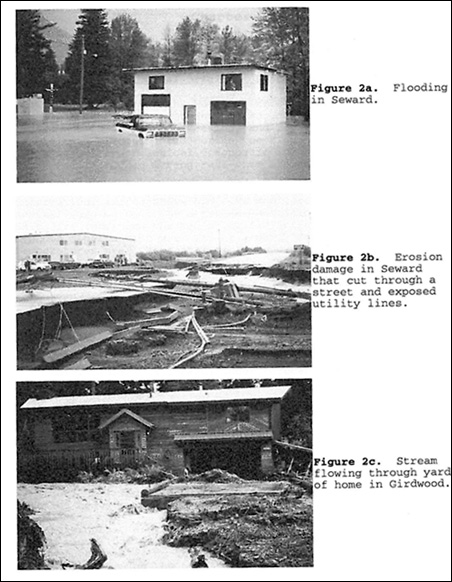

| National Weather Service Flood Report: South Central Alaska Floods Sep 19- October 2, 1995 |

One location famous for destructive flood events is on the Knik River near Palmer. From 1918-1963, Lake George formed behind the Knik glacier and annually emptied in July or August and then refilled. At the time, Lake George was the largest glacier dammed lake in Alaska and the regular release turned into such a spectacle that the area was designated as a Natural Landmark by the National Park Service. Something changed in the mid 1960s and after 1966, the lake stopped forming (Post and Mayo, 1971).

Another dramatic glacier dam release occurred from a lake on the Skilak Glacier above Skilak Lake on the Kenai River in 1969. The volume of the release was relatively small, causing less than a foot rise on Skilak Lake, but the timing of the release, in January, caused a breakup of the river ice which moved downstream and jammed the river causing flooded roads, homes and businesses in the middle of the winter and then freezing in place. Glacier dammed lakes on the Snow and Skilak glaciers release regularly on the Kenai River, typically every 2 years and cause a 2-4 foot rise on the river, which can result in flooding depending on the river level at the time of the release.

A final example of glacier dammed lakes is the one formed by the Hubbard Glacier in Russell Fiord. Hubbard glacier (upper left of the map) has threatened to close the gap entirely, preventing Russell Fiord from flowing into the Gulf of Alaska through Disenchantment Bay. In 2002, the glacier actually closed the gap sufficiently that the inflows to Russell Fiord exceeded the outflows through the restricted space by a considerable margin, raising the level of Russell Lake by 61 feet above sea level over a 2½ month period. When the lake started to erode through the glacial blockage, the outflow increased significantly, eventually releasing about 0.9 cubic miles of water. The peak outflow exceeded the peak historic flow of the Mississippi River at Baton Rouge by about 30%. The Hubbard Glacier continues to surge and eventually is likely to close off the gap entirely. Several federal agencies continue to monitor Hubbard Glacier because if the gap does close, the resulting lake could rise to 130 ft above sea level at which point it would spill into the Situk River near Yakutat which is a prized salmon and steelhead stream.

|

Learn More:

| Flood Hazard Information NWS Forecast Offices and River Forecast Centers (RFC) Covering Alaska | ||