Northern Indiana

Weather Forecast Office

Click a year to see the seasonal summaries, or read about the database and the 2002-2020 Data below

*Last Updated October 7th, 2023*

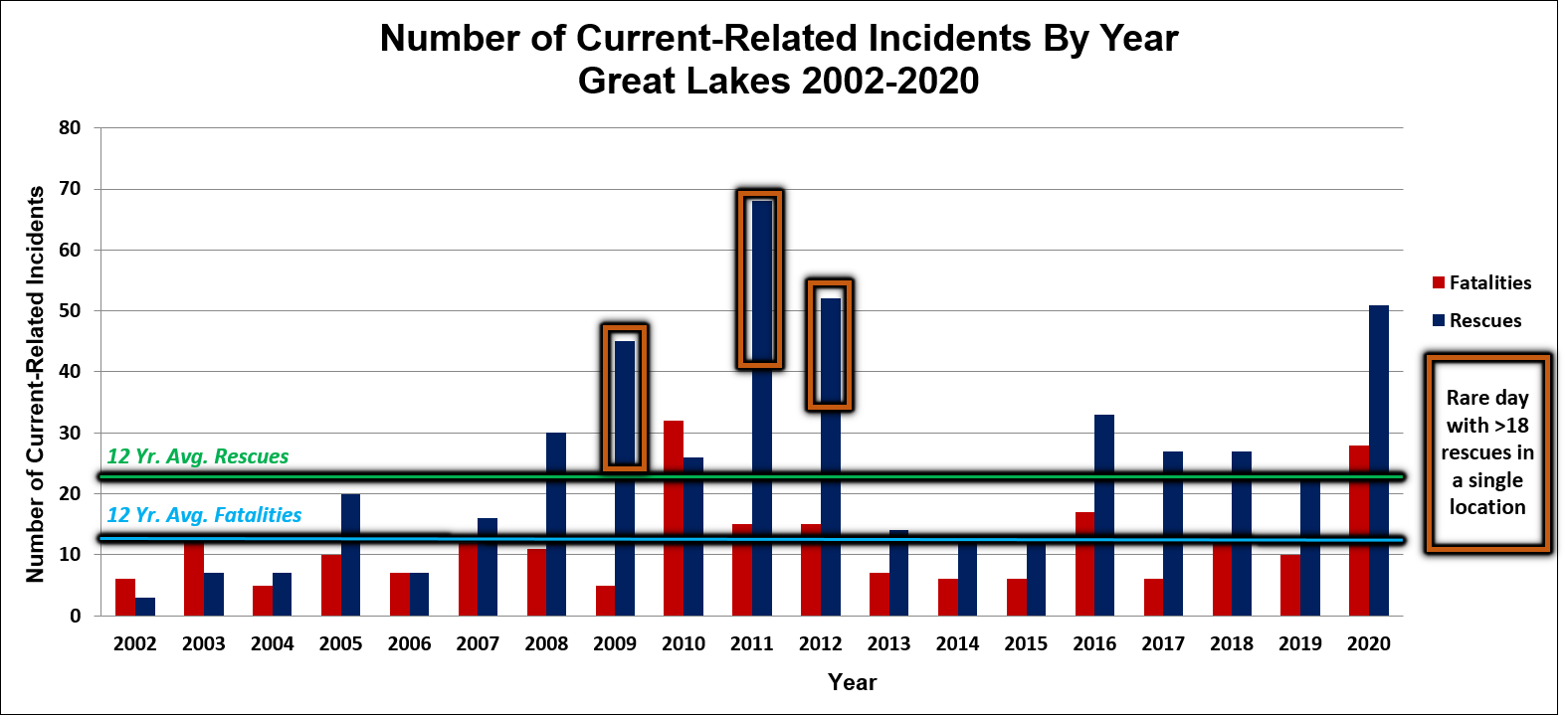

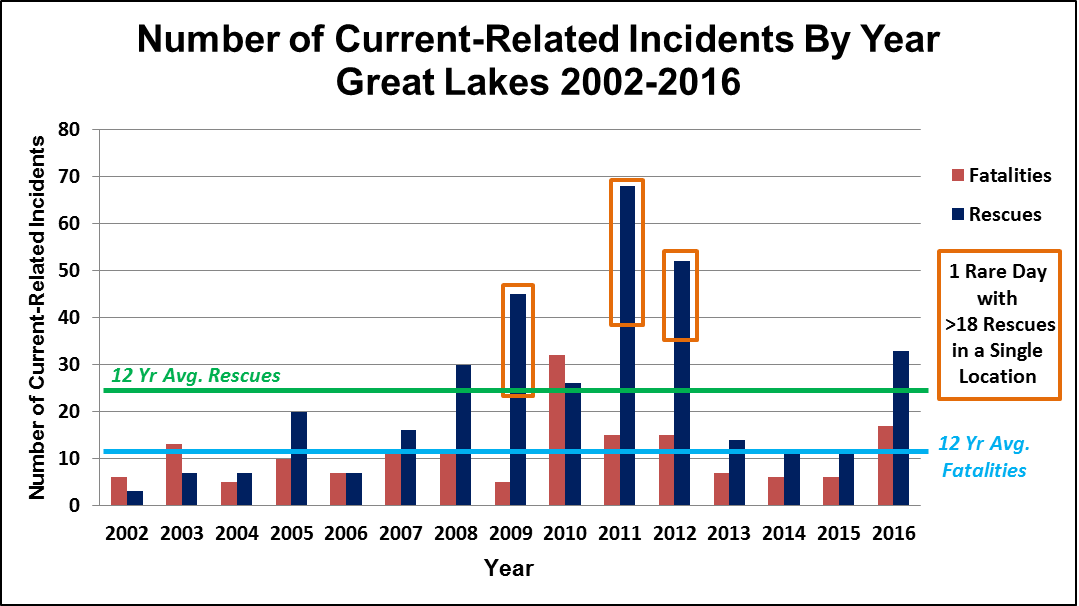

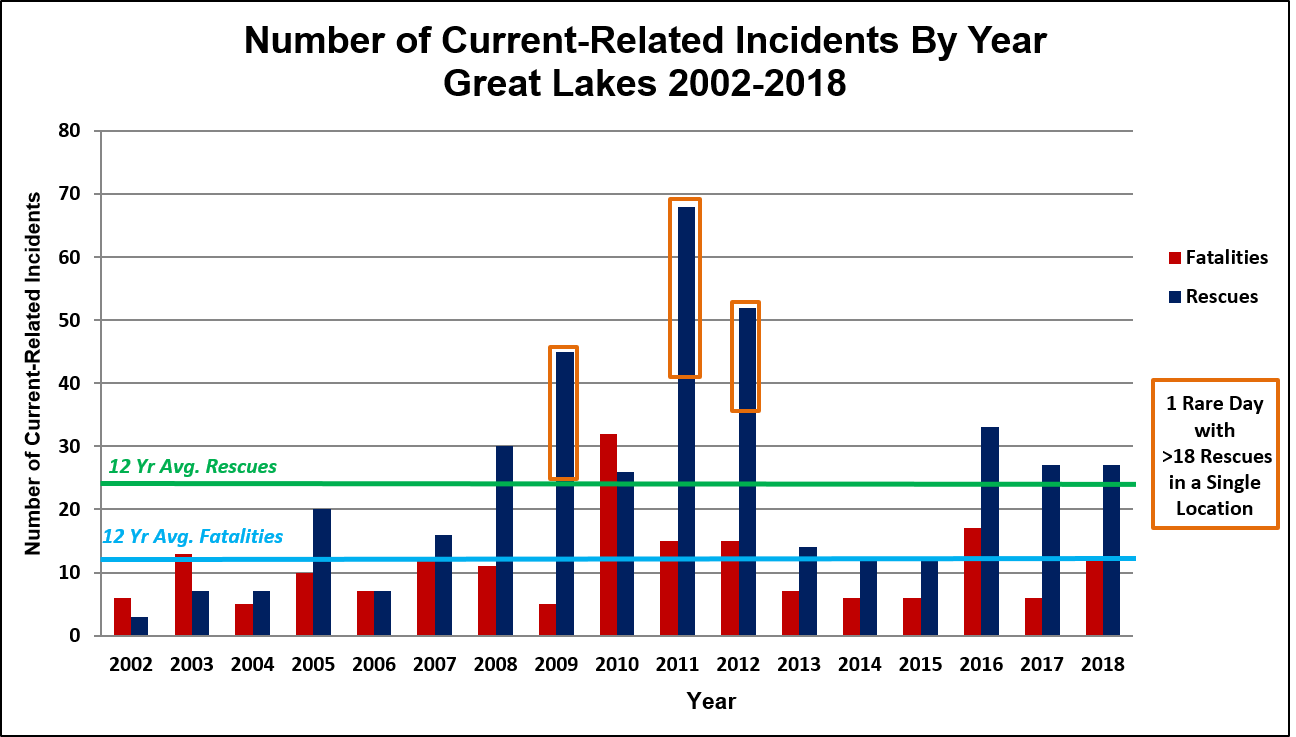

Each summer there are an average of 12 fatalities and 23 rescues due to dangerous currents on the Great Lakes (10 year average). The National Weather Service in Northern Indiana maintains the Great Lakes Current Incident Database (GLCID), an 19 year archive of current-related incidents. Case studies were completed on 703 current-related incidents to learn about where and when dangerous currents form. This research improves National Weather Service beach forecasts and beach hazards statements. Victim demographics were also collected to improve beach safety outreach and education efforts. The Great Lakes see millions of visitors per year at State Parks alone, most within a 3-4 month period in the summer. The key to being safe is knowledge. Beachgoers and the water safety community need to understand how, why, where, and when dangerous currents form.

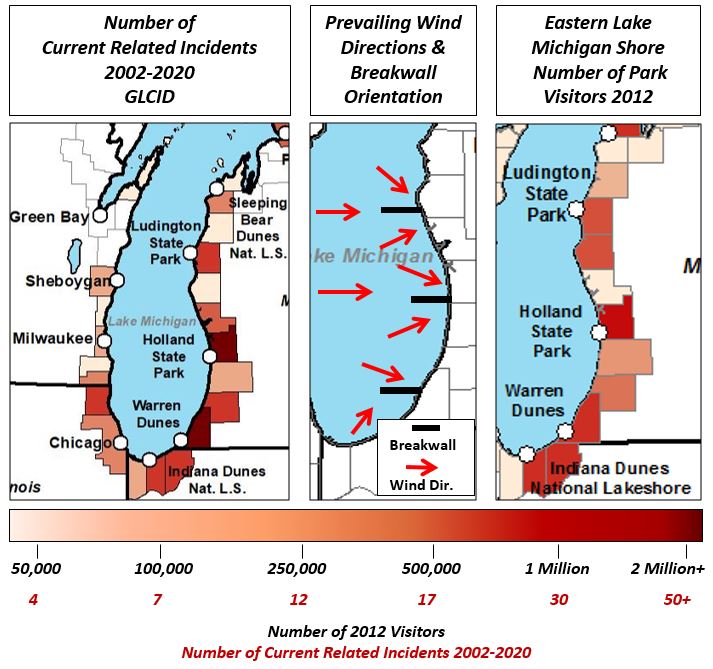

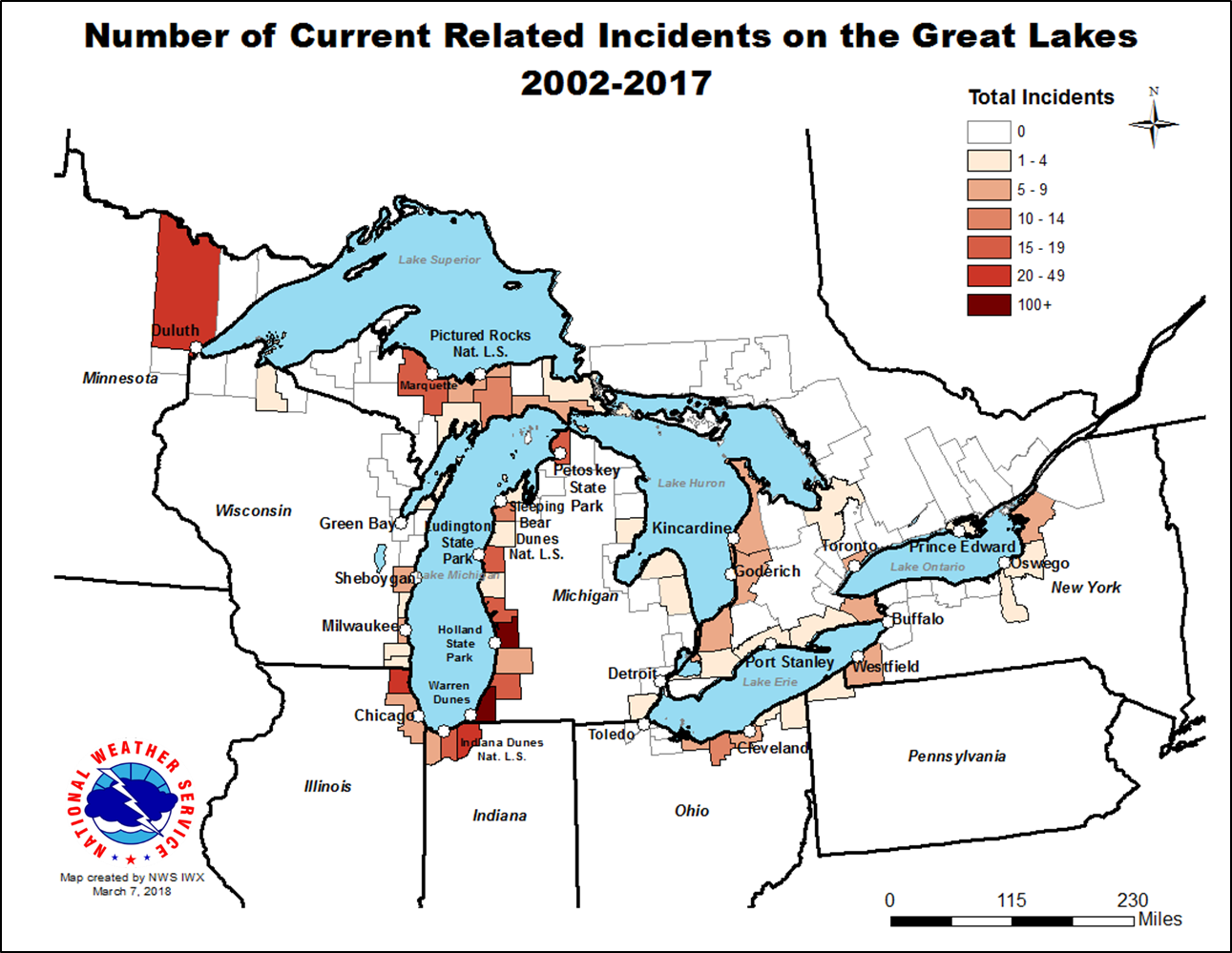

It is important to realize that although there are many incidents that occur at these beaches, the number of incidents must be kept relative to how many people visit the beaches each year. For example: Porter County Indiana, which includes the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, recorded 30 current-related incidents between 2002-2020, however over 2 million people visit the Indiana Dunes park alone EACH YEAR! Similarly, Ottawa County in Michigan has seen more than 130 incidents over the years, however they also see around 2 million visitors per year at Holland State Park alone. These beaches are all safe and fun to swim at, however beachgoers must remain alert to the changing weather and wave conditions and heed the advice of park patrol and lifeguards.

Database History

In 1998, 12 year old Travis Brown drowned in a rip current at a Lake Michigan beach along US-2 in Mackinac County, Michigan. Prior to that incident, people didn't think rip currents could happen on the Great Lakes. In memory of Travis, the Brown Family started the Mackinac Water Safety Review team, which included Michigan Sea Grant, local law enforcement, and other members of the community. Eventually, they reached out to the National Weather Service in Marquette, Michigan to see if they could start a forecast on the Great Lakes to alert the public about dangerous waves and currents. One of the forecasters Dave Guenther (now retired) agreed to join the group, and get forecasts started on the Great Lakes. To learn about where, why, and when the currents developed, Dave started the Great Lakes Current Incident Database. Once Dave retired in January 2011, he handed the task to Megan Dodson, who now maintains the database from NWS Northern Indiana. Forecasts are now done at nearly all NWS Offices on the Great Lakes, and outreach has greatly improved as a result of the database. Thanks to a collaborative project between Michigan Sea Grant and the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy's Coastal Management Program, the database is available online.

Searching the Database & Reporting an Incident

To search the database for more detailed information, click here. To submit a current-related incident into the database, please use this form. Any incidents submitted using the form will be sent to Megan Dodson for review before being entered in. We accept incidents that occurred from 2002 to present. If you have any questions or concerns, email Ms. Dodson at NWS Northern Indiana (megan.dodson@noaa.gov).

About Swim Season Summaries

Each swim season, which runs from roughly May 1st to October 15th each year, NWS Northern Indiana writes up a summary of the incidents that occurred that year. The summary is usually posted by January each year, but delays may occur if there is difficulty in confirming incidents with authorities (pending final police reports, witness/survivor interviews, etc.).

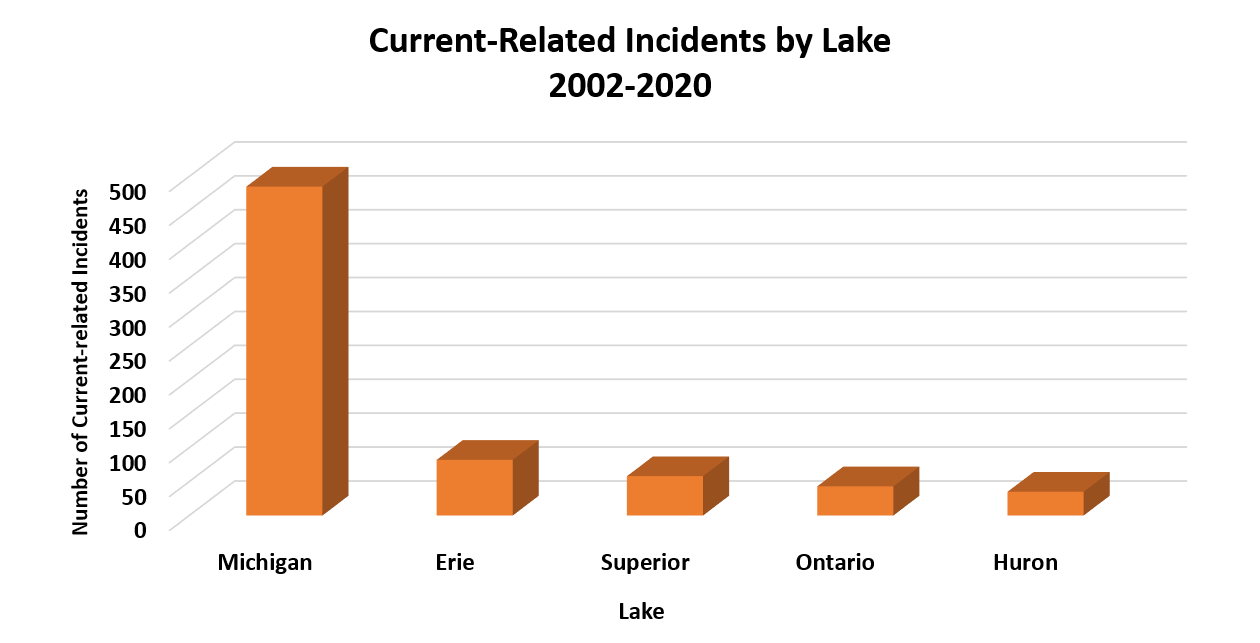

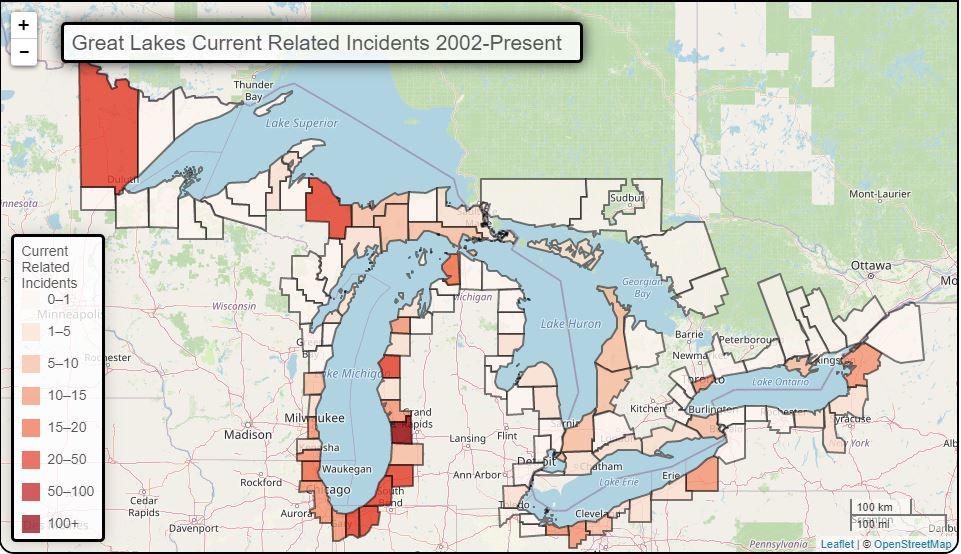

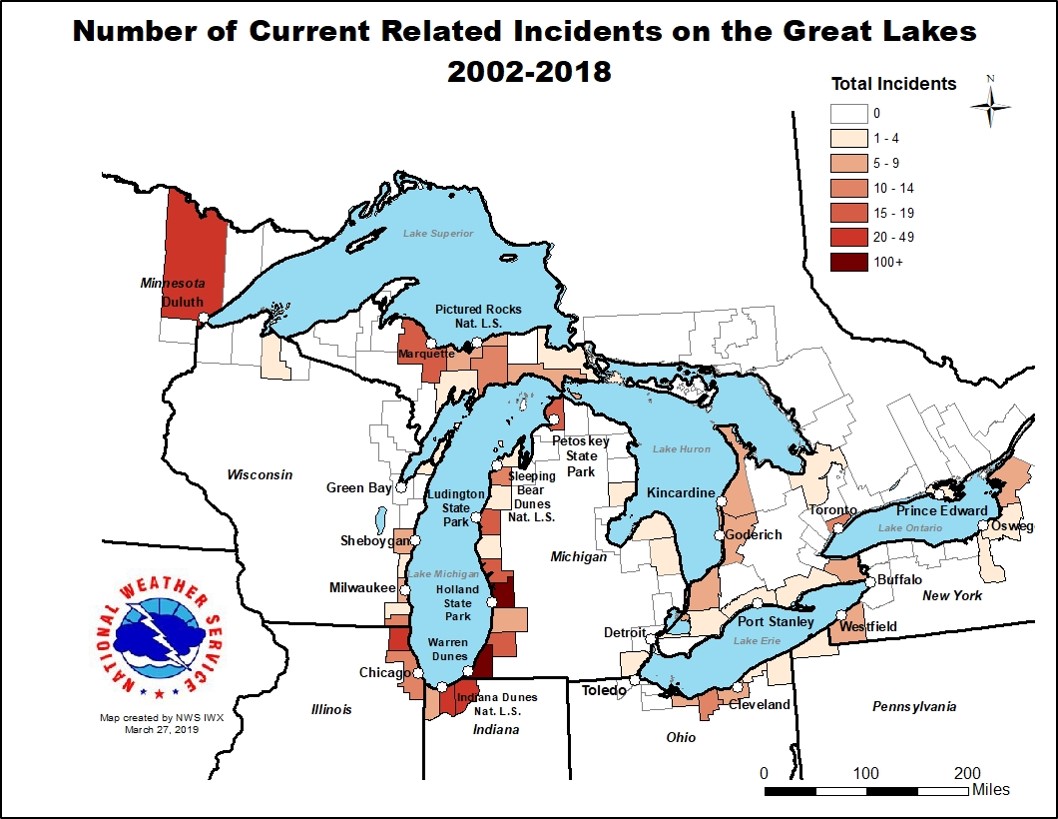

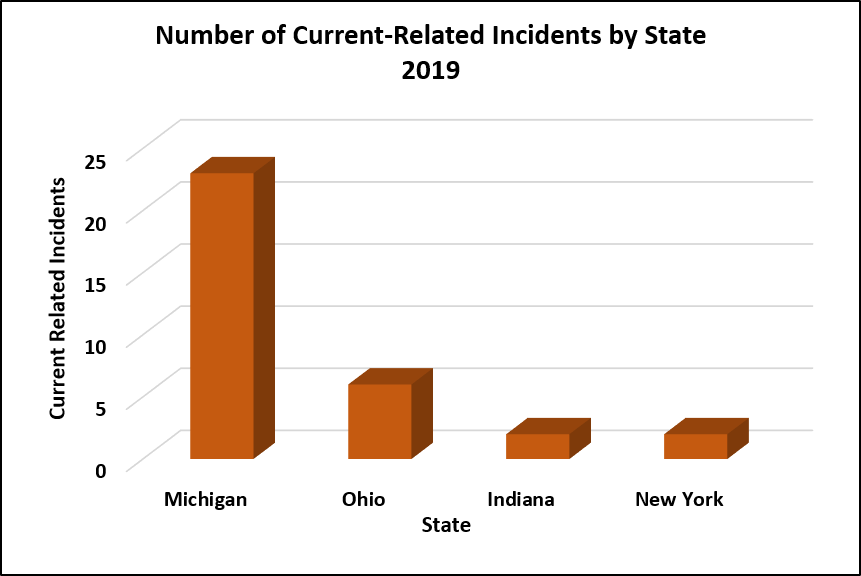

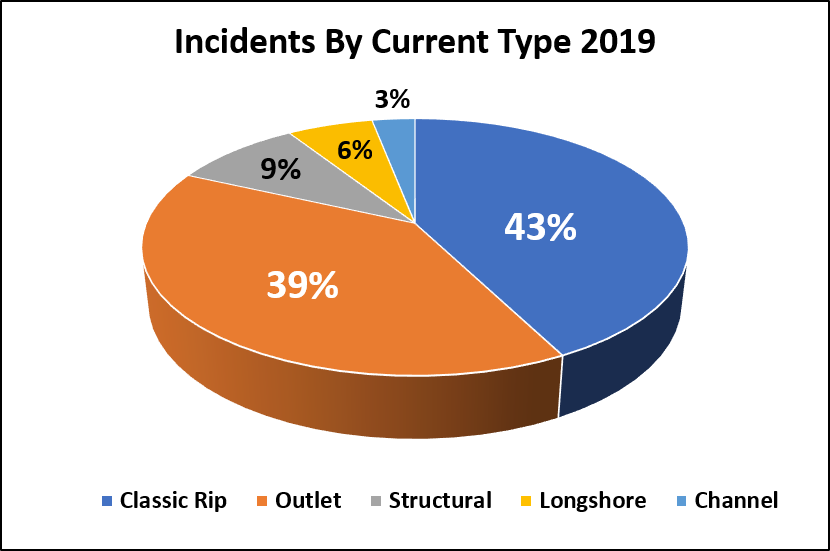

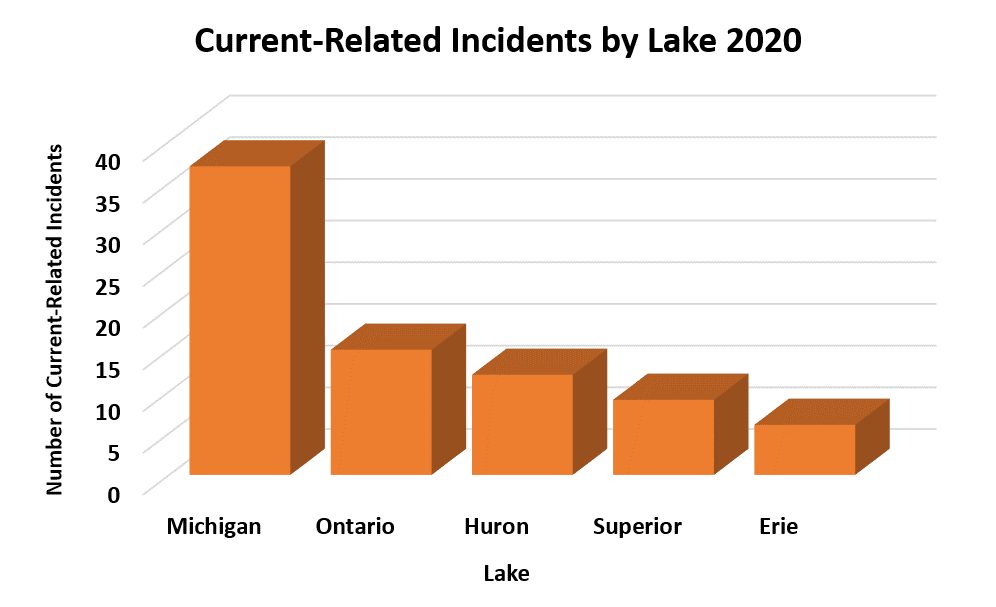

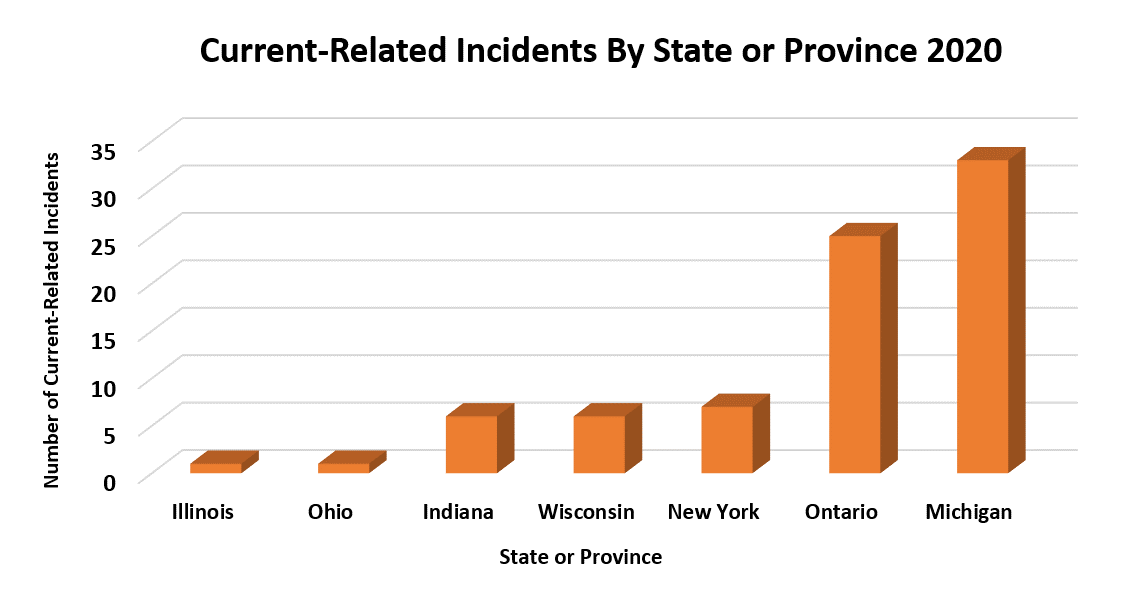

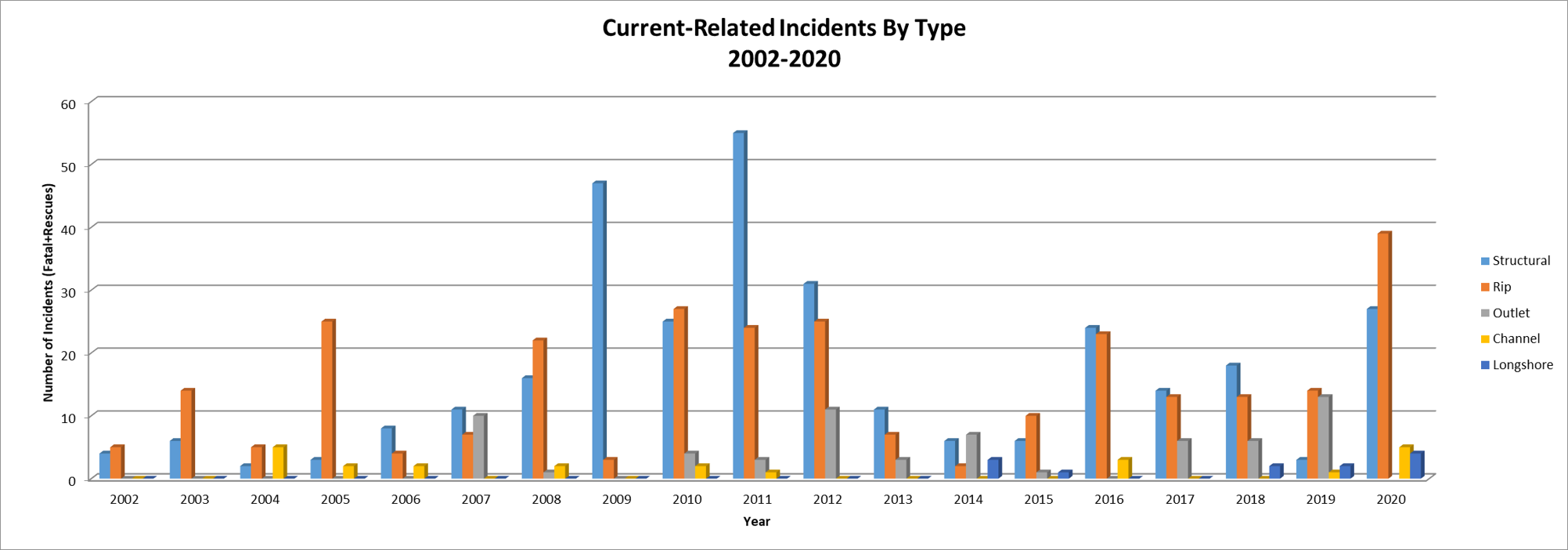

There are several dangerous currents that can cause a swimmer to struggle on the Great Lakes. The currents that have most often claimed lives since 2002 are structural currents, rip currents, outlet currents, longshore currents, and channel currents. According to the National Weather Service (NWS) Great Lakes Current Incident Database (GLCID), the Great Lakes averages around 12 drowning fatalities per year related to dangerous currents. Most of these dangerous current incidents occur on Lake Michigan (Fig. 2) because its eastern shores are positioned favorably for current development, and it is a popular tourist destination (Fig. 7). Note that the incidents collected in the GLCID are current related, meaning currents may have been only a partial cause of the fatality or rescue (likely a combination of high waves and currents).To learn about the various types of currents, visit this webpage.

When Great Lakes current related incidents are analyzed, several commonalities emerge. First, a majority of the incidents occur during, or just after high wave action. Most of the wave periods during the incident were short, meaning there is less time in between each incoming wave (less time for swimmers to recover in between waves). Waves were likely an equal contributor in many of the incidents. Once a swimmer is pulled into deeper water by the current, the waves quickly become overwhelming. Secondly, most of the incidents occur near shoreline structures, such as a breakwall or pier.

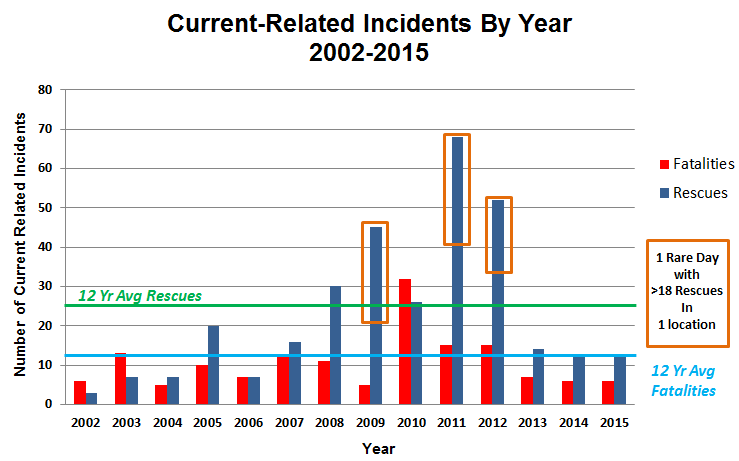

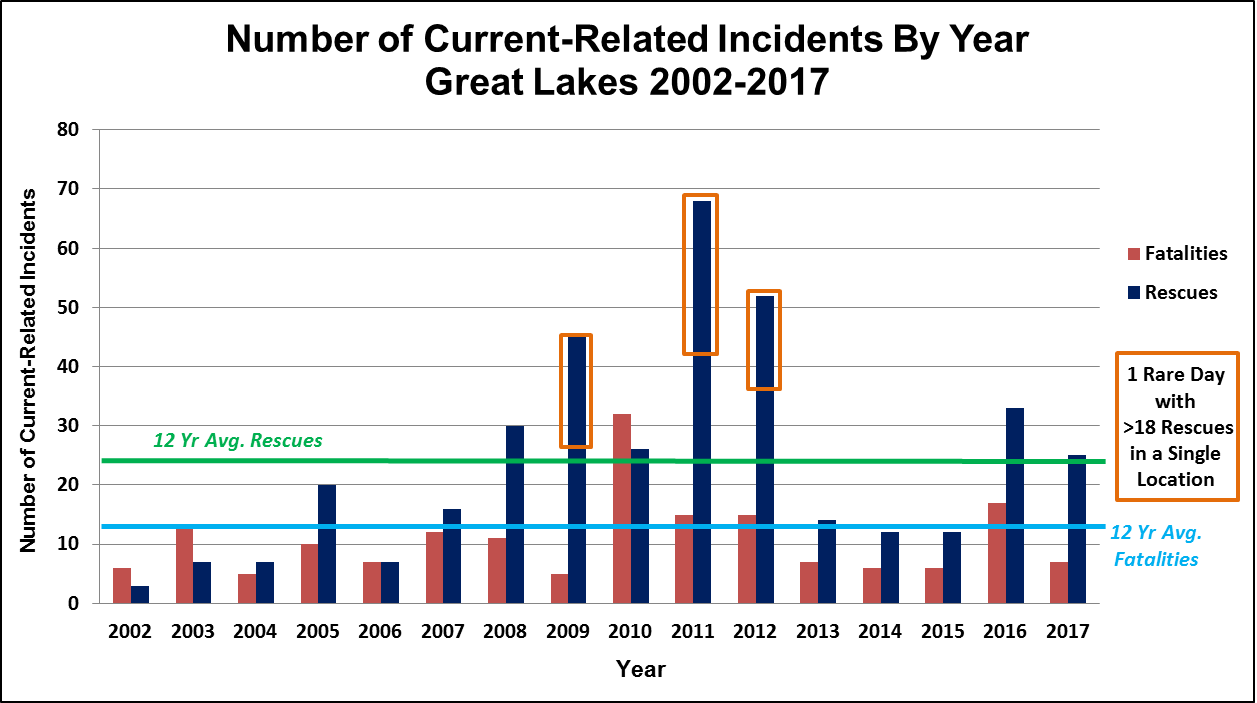

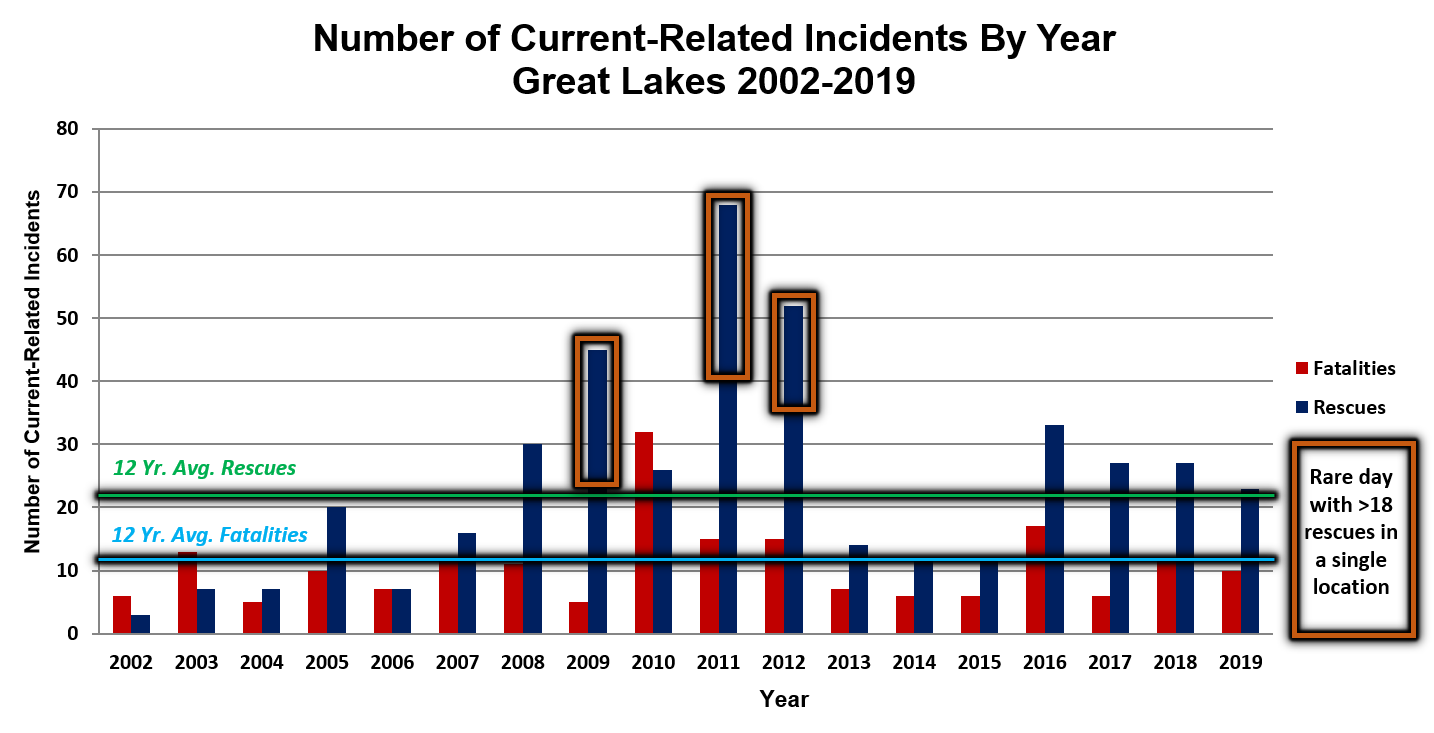

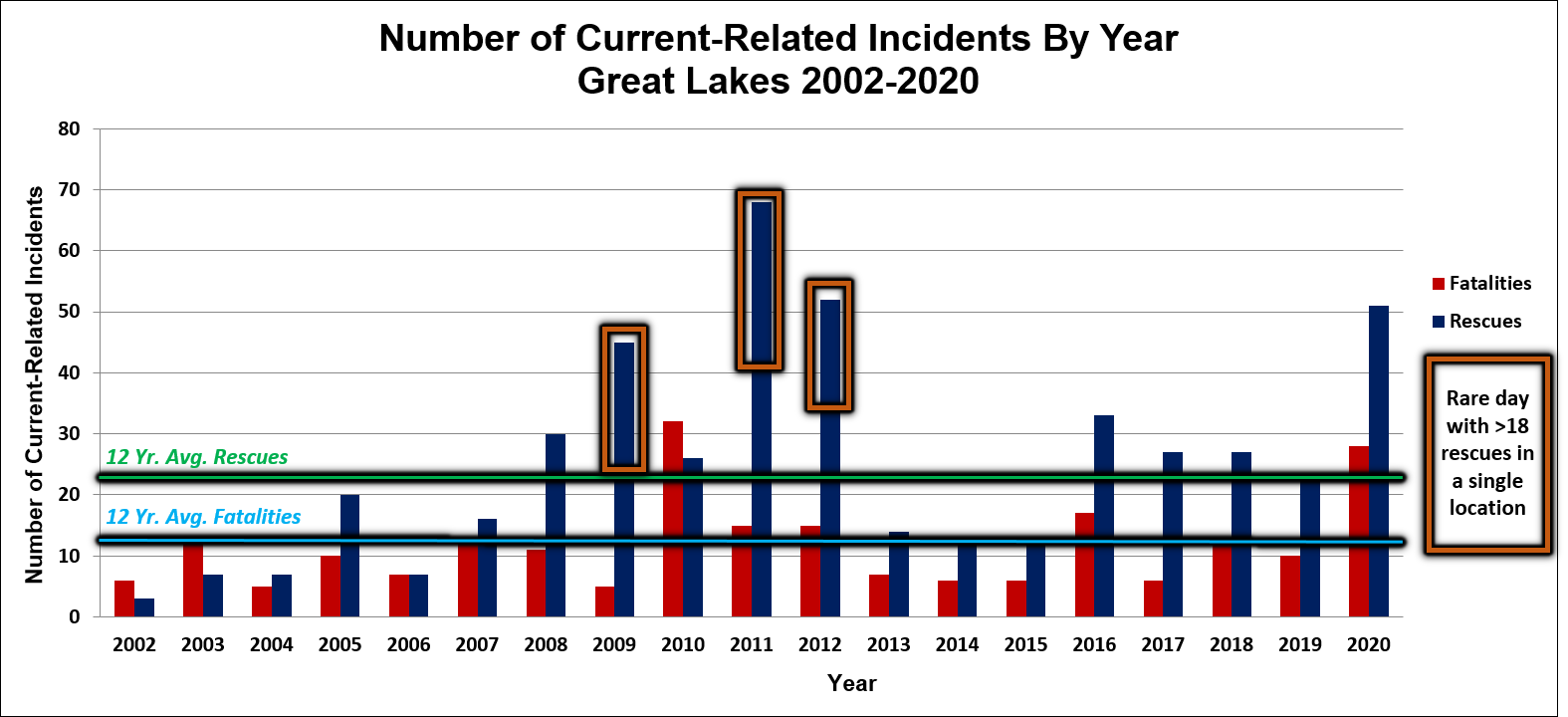

Fig. 1. A graph of current related incidents from 2002-2020. The years of 2009, 2011, and 2012 were years where there was one day with greater than 18 rescues, which are marked by orange boxes in this graph. Averages are marked by the blue (fatalities) and green lines (rescues) (GLCID, 2020).

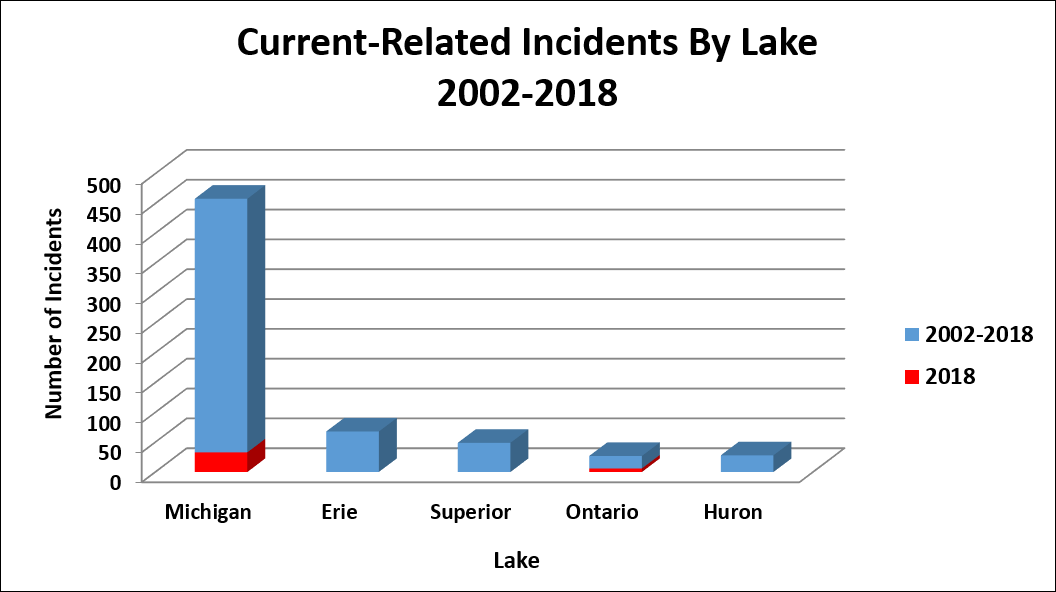

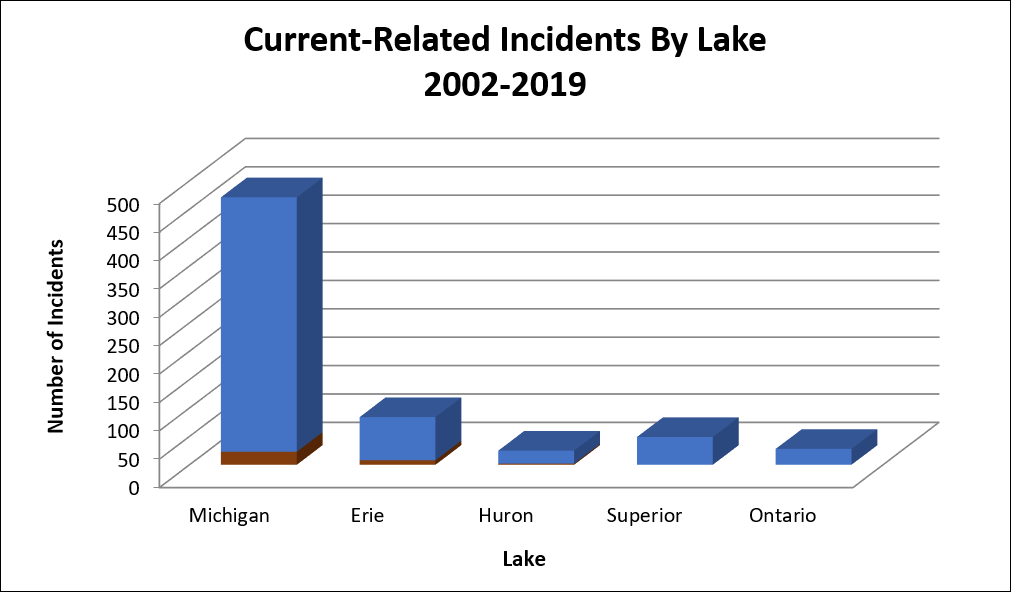

Current-Related Incidents By Lake

Lake Michigan has the most current related incidents of all the Great Lakes. This is because Lake Michigan (mainly the eastern shore) is favorably aligned for the weather and wave conditions conducive to current formation, and many beaches along the shoreline have sandbars and breakwalls. Additionally, Lake Michigan sees extensive tourism. One limitation of the database is the lack of data we have from the Canadian shores of the Great Lakes. As a result, it is likely that the numbers for Lakes Erie, Huron, Ontario, and Superior are under reported in comparison to Lake Michigan.

Fig. 2. Number of current-related incidents by Great Lake for 2002-2020. "Incidents" include both rescues and fatalities. GLCID (2020).

Conditions that Lead to Dangerous Currents and High Wave Action

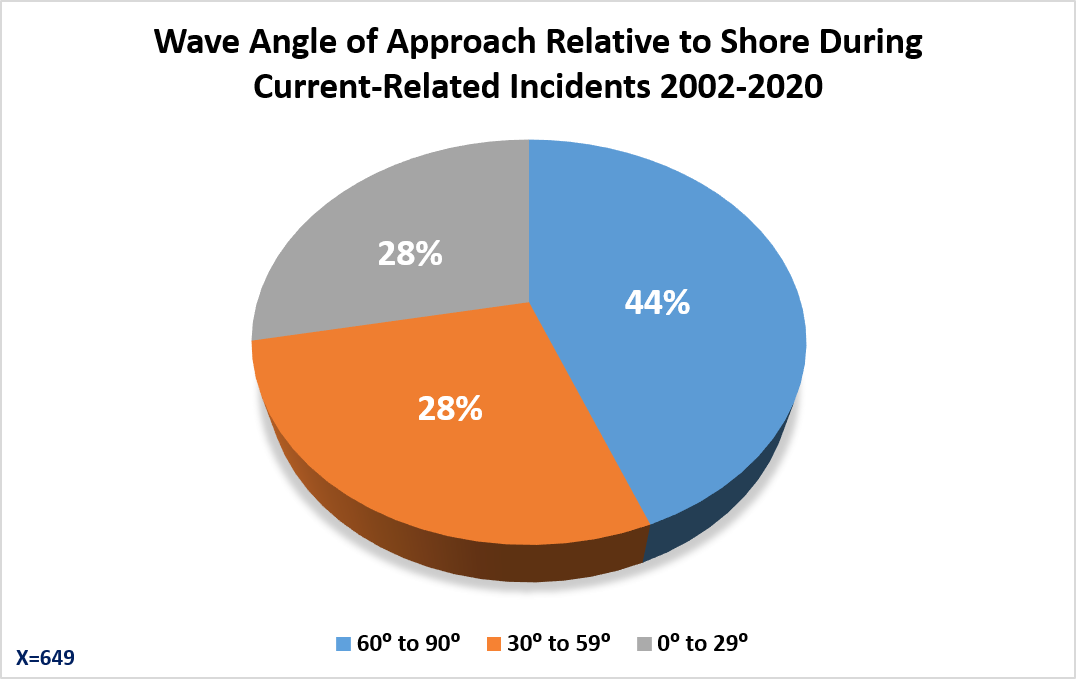

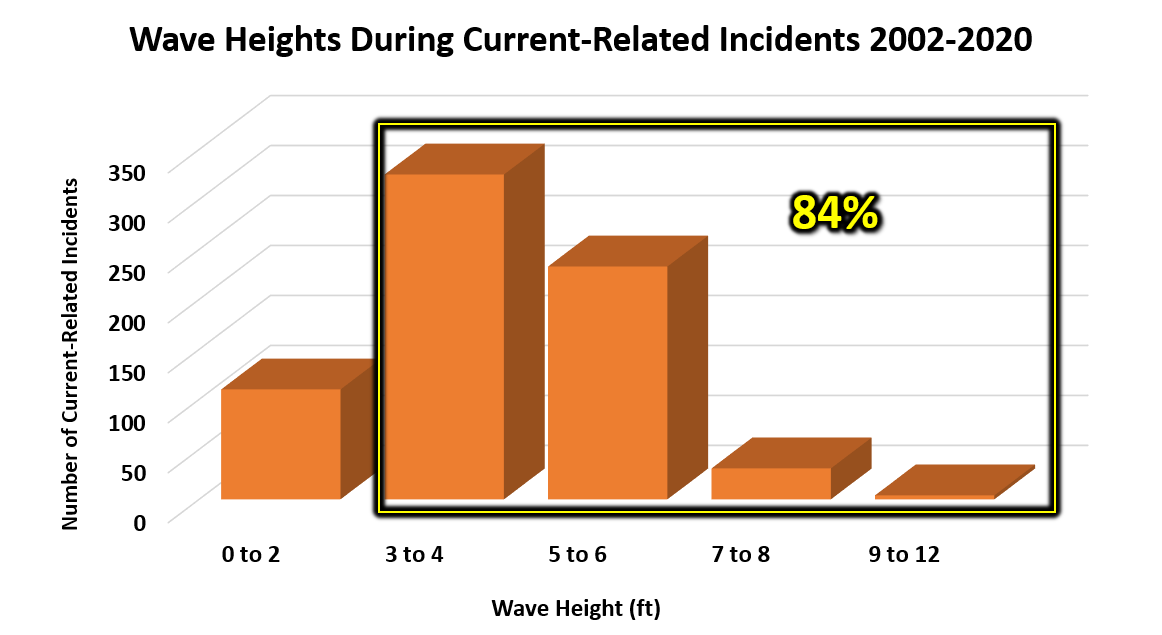

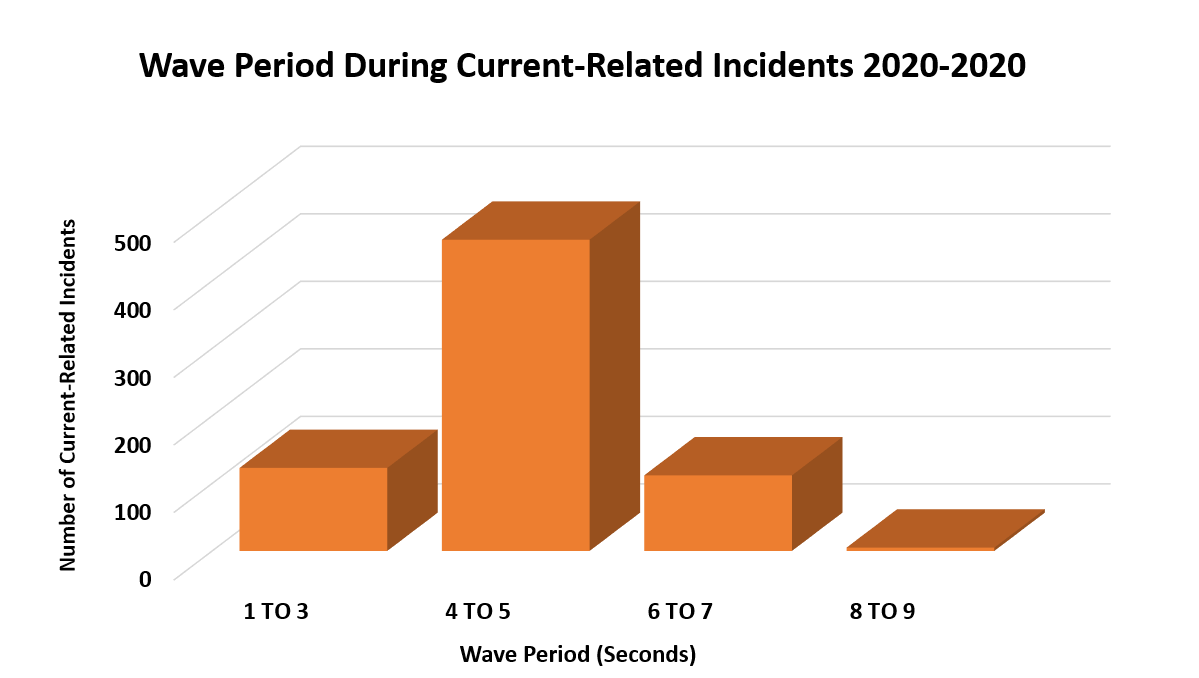

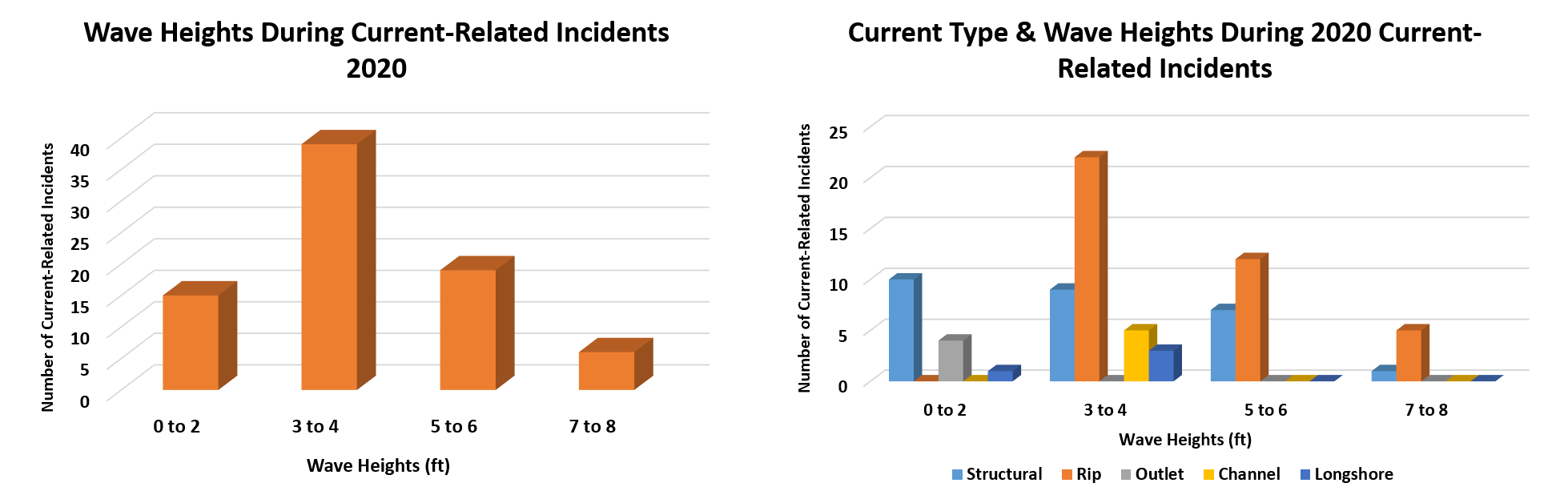

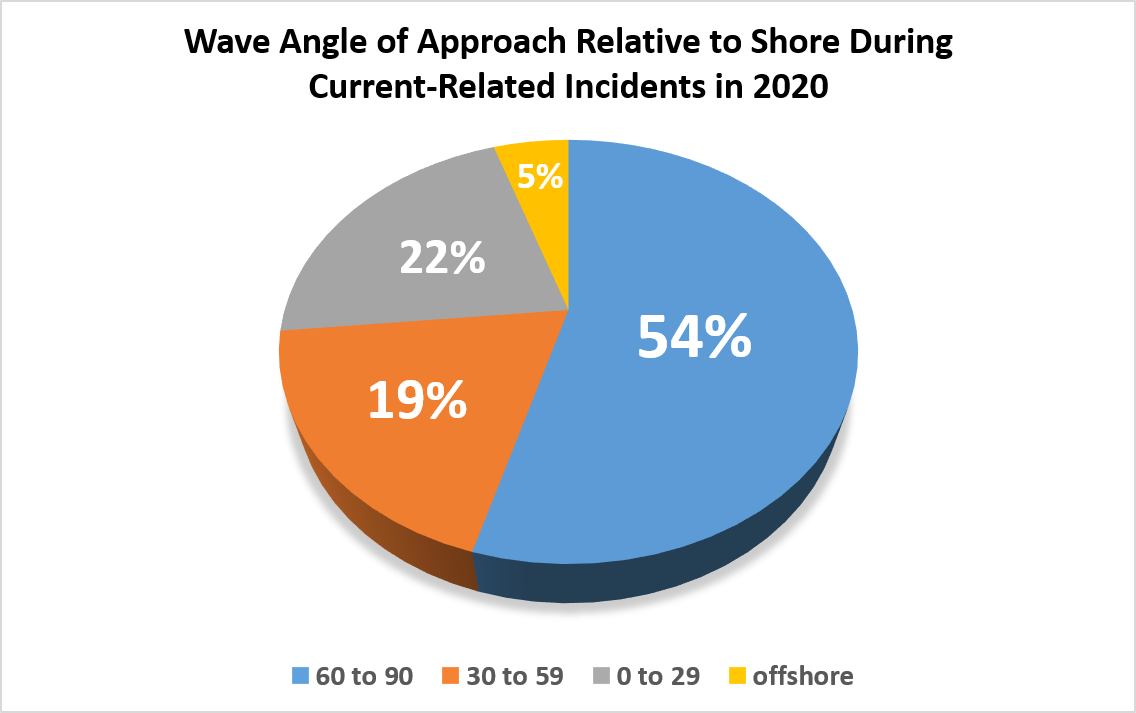

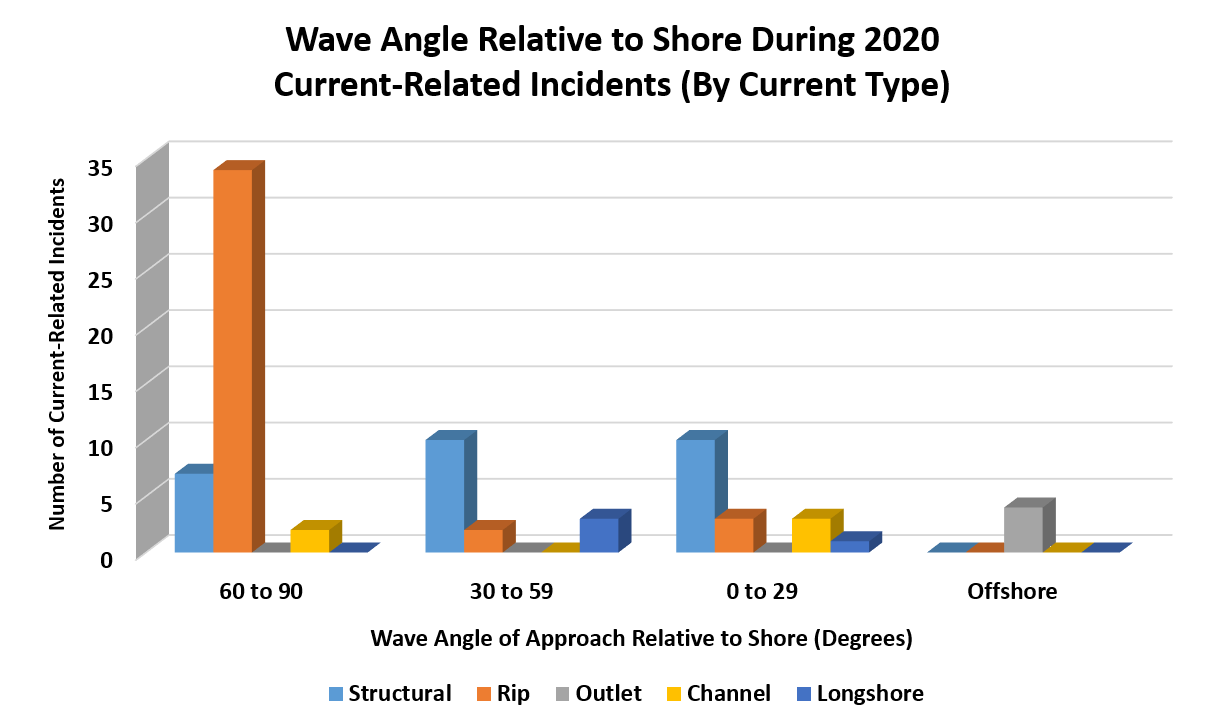

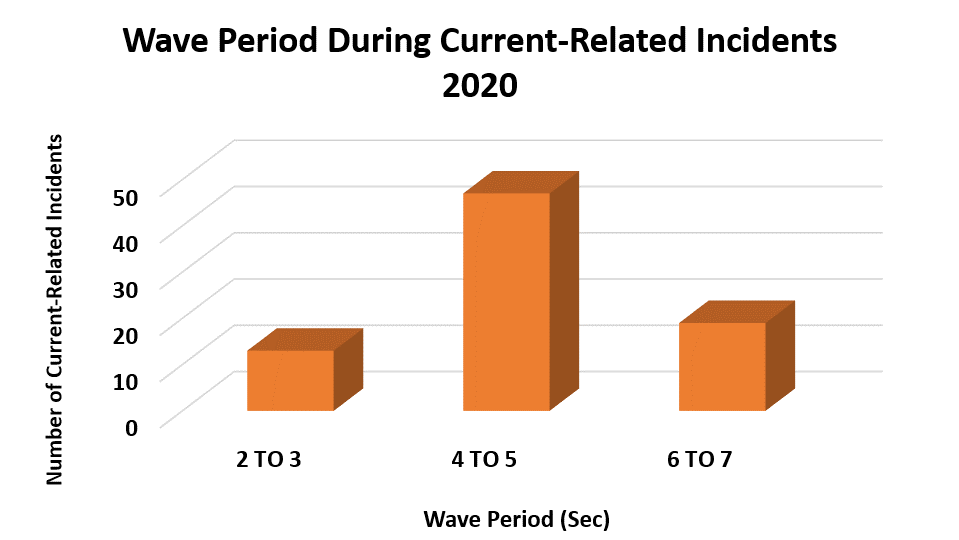

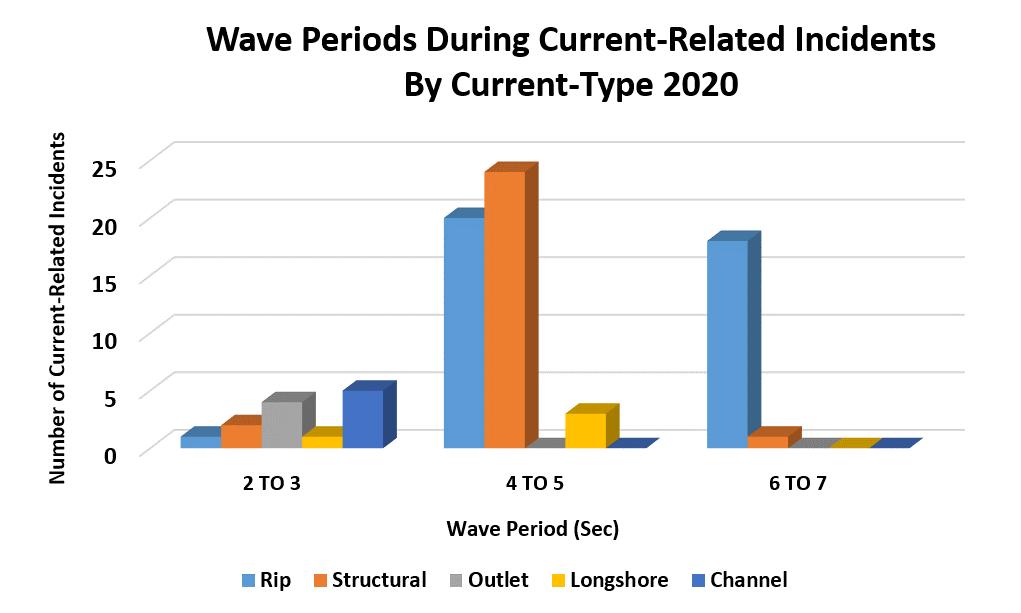

Dangerous currents develop on the Great Lakes when the waves approach the beach around a 30 to 90 degree angle relative to shore (Fig. 3), and wave heights are 3 feet or greater (Fig. 4). Moderate to high waves are conducive to currents because they 'pile up' the water near the beach, which causes the surface of the water to be uneven. Water can also 'pile up' near a shoreline structure, like a breakwall, or near a river mouth. The water must return into the lake or the ocean, so it flows outward as a rip current, structural current, or outlet current. Longer wave periods (the time in between each successive wave) also work to 'pile up' water near the beach. On the ocean, rip currents are typically associated with wave periods greater than 9 seconds, but can occur when wave periods are as short as 4 seconds. On the Great Lakes, most of the incidents occur when wave periods are 4 to 5 seconds (Fig. 5), which is reasonable given the average wave period on the Great Lakes is 3 to 4 seconds.

Fig. 3. Orientation of the winds (waves) relative to the shore during outward flowing current-related incidents (structural, rip, outlet). Waves moving onshore at a 60-90 degree angle will most often lead to rip currents, whereas waves moving onshore at a more oblique angle (especially 30-59 degrees) will produce primarily structural currents. Keep in mind, however, that 30-59 degree angle approaches can also lead to rip currents that develop more diagonally to shore (versus perpendicular to shore). Most of the incidents on the Great Lakes are caused by structural and rip currents, so it is reasonable that we see a large number of the incidents occurring when waves are approaching the beach at oblique angles (GLCID, 2020).

Fig. 4. A majority (84%) of current related incidents occur during moderate to high wave action. Incidents decrease dramatically after 6 feet because most people are too intimidated to swim when waves are above their head (GLCID, 2020)

Fig. 5. Wave periods during current related incidents on the Great Lakes. Wave periods are typically 4 to 5 seconds. Longer wave periods are more conducive to developing strong rip currents on the ocean and the Great Lakes. However, wave periods on the Great Lakes are fetch limited (limited by the distance the wind can travel across the lake), so periods are often less than 7 seconds (GLCID, 2020).

Current Related Incidents on the Great Lakes

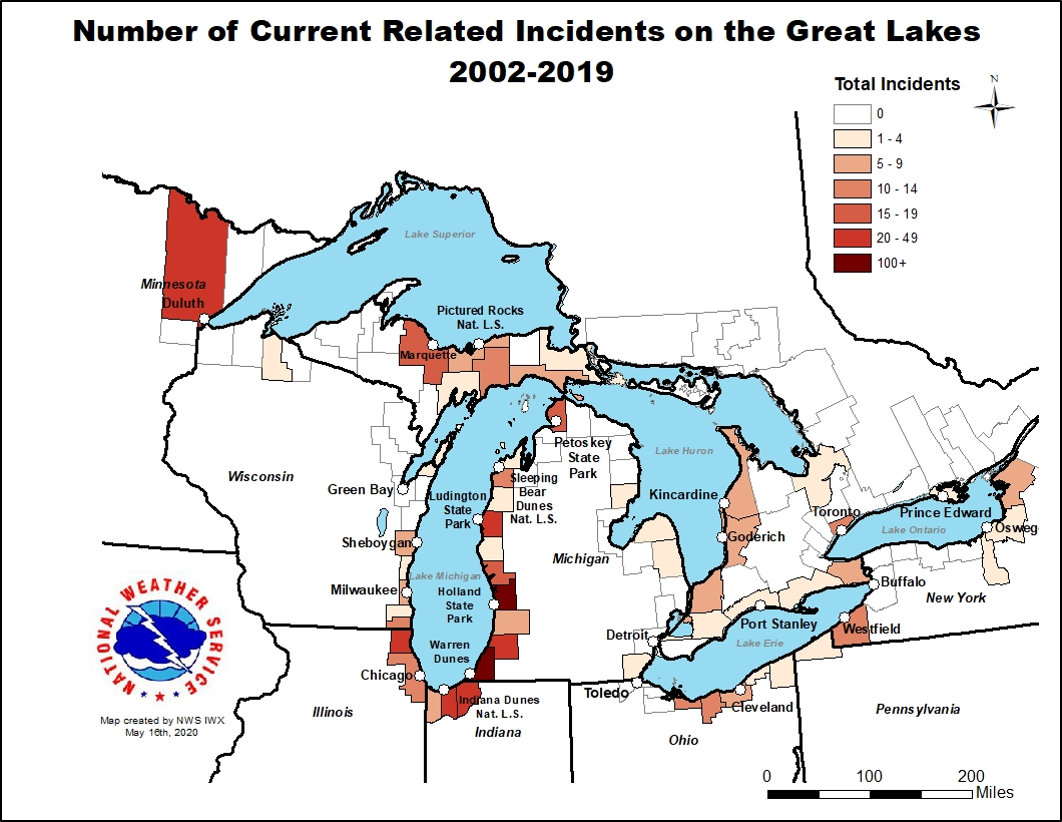

Fig. 6. Shows the number of current related incidents on the Great Lakes by county (for an interactive version, visit the main page). The prevailing wind directions over the Great Lakes are west, southwest, and northwest (Center, Fig. 7). This is why a majority of the incidents (seen as the darker red colors) are seen on the eastern, southern, and northern shores of each of the Lakes. These wind directions are often associated with the passage of a cold front (which causes winds to veer from southwest to northwest over a time period). With stronger winds out of these directions, waves can get high on the lakeshore, which can develop dangerous currents (GLCID, 2020).

Lake Michigan: Tourism + Favorable Conditions and Features for Current Development

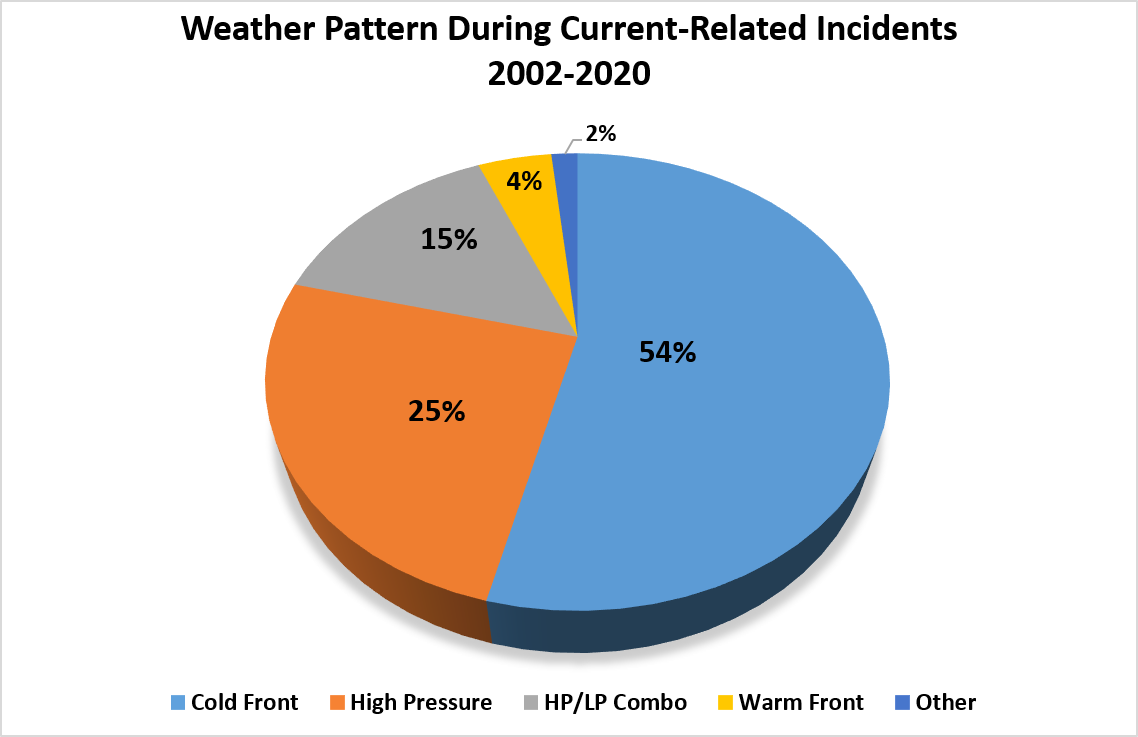

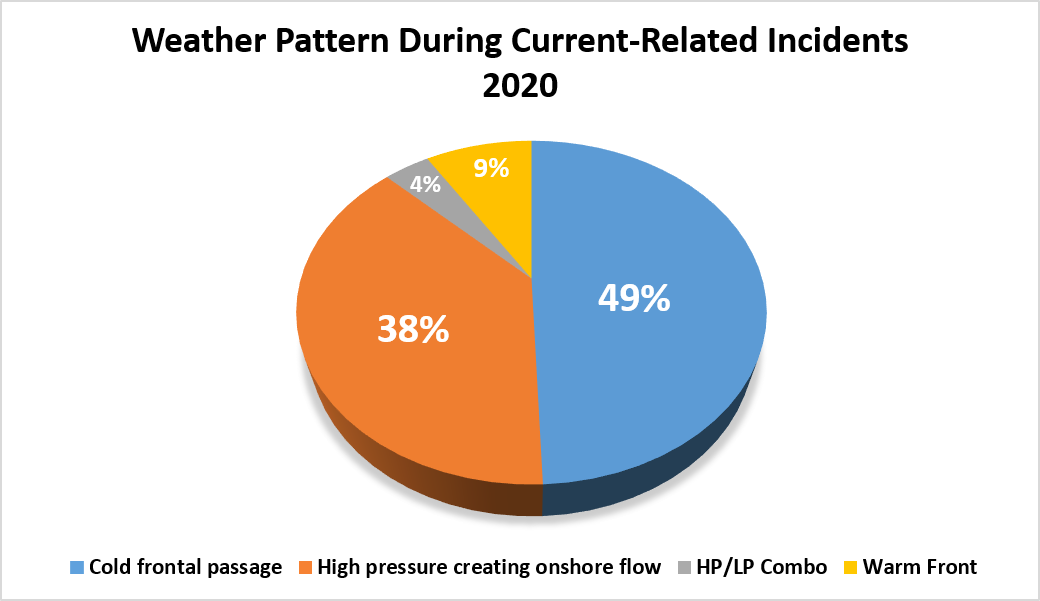

Onshore directed winds and waves, shoreline structures, warm water and air temperatures, and popular tourist destinations all come together in late July-early August to bring higher numbers of incidents (rescues and fatalities) to the southeastern shore of Lake Michigan (Fig. 7). The most common pattern associated with current-related incidents on the Great Lakes, is the passage of a cold front because it often brings stronger onshore winds, and hence larger waves (Fig. 8).

Fig. 7. The map on the left depicts the most common location for current related incidents (GLCID, 2002-2019). The middle map depicts the breakwalls (black rectangles) and the most common wind directions (red arrows) over Lake Michigan. The breakwalls are not realistic in size/length-they were drawn large for easy visibility. The map on the right is the number of visitors to state and national parks in 2012. The combination of frequent favorable wind directions for current development, beach features (breakwalls, sandbars), and popularity cause Lake Michigan to have more incidents than all of the other Great Lakes.

Fig. 8. The most common pattern observed during outward flowing current related incidents on the Great Lakes is the passage of a cold front. HP/LP stands for high and low pressure-where the pattern may have been such that the beach was in between both features. Does not include channel current/longshore current related incidents (X=672 incidents). GLCID (2020).

It is important to realize that although there are many incidents that occur at these beaches, the number of incidents must be kept relative to how many people visit the beaches each year. For example: Porter County Indiana, which includes the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, recorded 30 current related incidents between 2002-2020, however over 2 million people visit the Indiana Dunes park alone EACH YEAR! Similarly, Ottawa County in Michigan has seen more than 130 incidents over the years, however they also see around 2 million visitors per year at Holland State Park alone. These beaches are all safe and fun to swim at, however beachgoers must remain alert to the changing weather and wave conditions and heed the advice of park patrol and lifeguards. Additionally, visitors should always stay away from shoreline structures and river mouths, as dangerous currents often form there.

For references, click HERE.

Overview

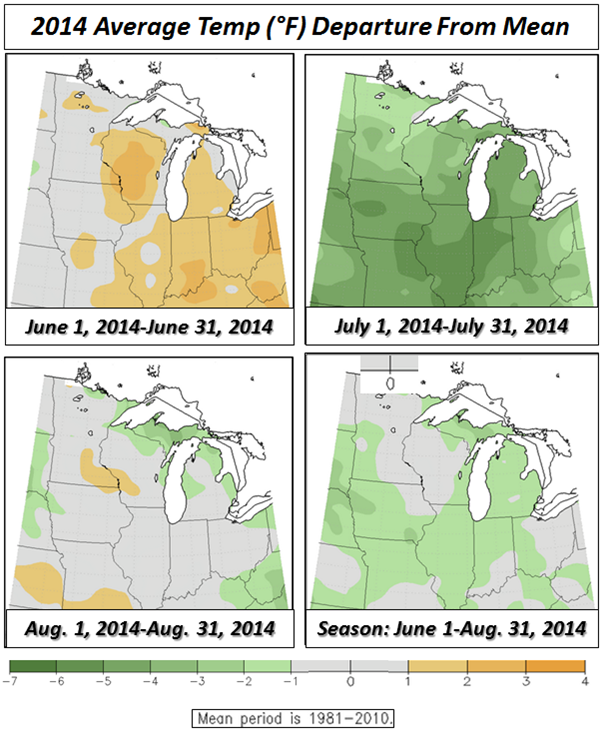

Air and water temperatures across the Great Lakes were colder than normal throughout the 2014 swim season. This led to less current related fatalities and rescues. July was particularly cool, with temperatures averaging 6 to 7 degrees below normal (Fig.1). According to the Summer 2014 climate summary from the Grand Rapids National Weather Service (NWS), locations in southwestern lower Michigan (Lansing, Grand Rapids, Muskegon, and Jackson) didn't even reach 90 degrees until after August 31st. For Grand Rapids this was the first time since 1951 to see such a late season arrival of a 90-degree day. Similarly, according to the Summer 2014 Climate Summary from the NWS in Cleveland, Ohio, the average maximum temperatures in Cleveland for the summer season were 1.9 degrees below normal. Temperatures in Cleveland only climbed above 90 degrees three times during the summer, which is about five times less than a typical summer in that area.

Fig. 1. Average Mean Temperatures: Departure From Mean (F). Darker green shows cooler than average temperatures. Darker yellow shows warmer than average temperatures. From the Midwestern Regional Climate Center

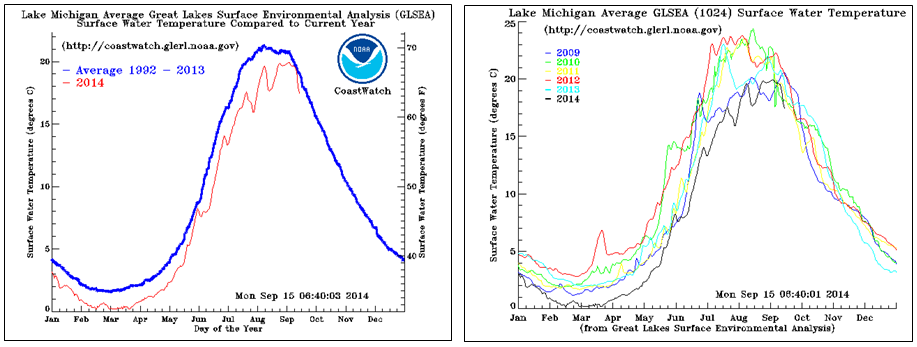

With the cold winter season of 2013-2014 and a cooler summer, water temperatures on the Great Lakes struggled to reach the average. Lake Michigan saw average surface water temperatures rivaling those of 2009, reaching a peak of only 68 degrees F in August (Fig. 2). Meanwhile, icebergs were still floating on Lake Superior until roughly June 10, 2014 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2. Lake Michigan Average Surface Water Temperatures (1992-2013) compared to 2014 (left). Comparison of Lake Michigan Average Water Temperatures (Deg. C) 2009-2014. Images from The Great Lakes Environmental Research Lab.

Fig. 3. Ice at McCarty's Cove, Marquette Mich. on Lake Superior in early June, 2014.

Image courtesy of Don Rolfson.

Cooler water temperatures through the season also kept conditions over the lakes relatively stable during a better part of the swim season, which led to less days where high swim risk criteria was reached (i.e. waves 3 to 5 feet). Additionally, many of the days with current-conducive conditions featured poor swimming weather, such as colder air temperatures and rain showers.

2014 Current Incident Database Summary

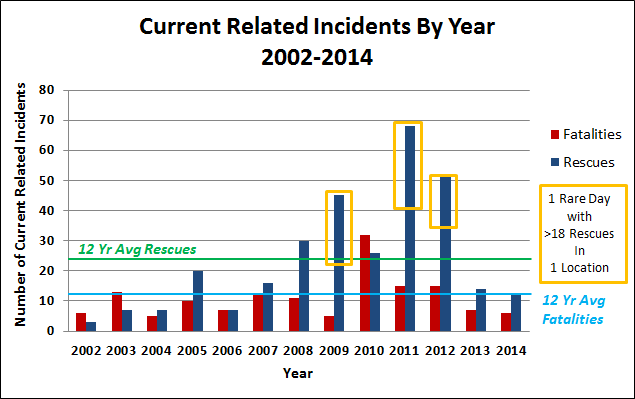

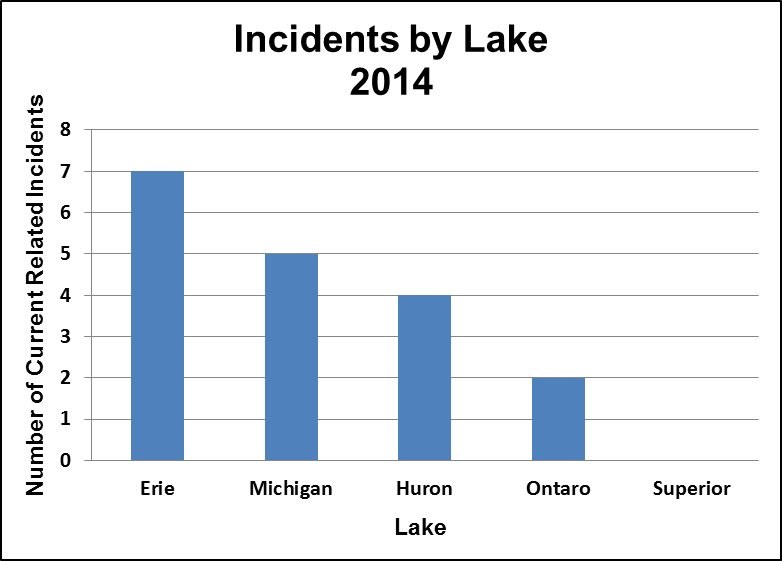

During the 2014 swim season there were 6 fatalities and 12 rescues related to currents on the Great Lakes, which is below the 13 year average of around 11 fatalities and 25 rescues per year (Fig. 4). Lake Erie and Lake Michigan saw more than half of the incidents (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4. A graph of current related incidents from 2002-2014. The years of 2009, 2011, and 2012 were years where there was one day with greater than 18 rescues, which are marked by orange boxes in this graph. The swim season of 2014 had below average current related fatalities and rescues (2002-2013 average). Averages are marked by the light blue and dark green lines. GLCID, 2014.

Fig. 5. Current Related Incidents by Lake in 2014. GLCID, 2014.

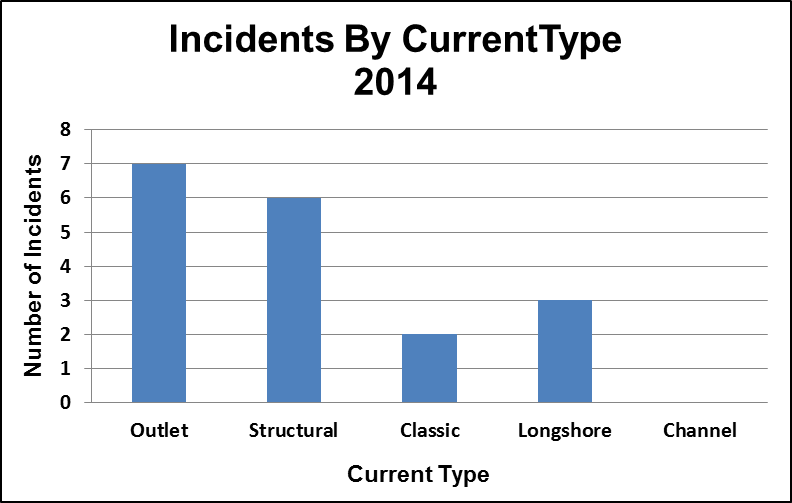

Approximately 39 percent of the current related incidents in 2014 occurred near river mouths, which is unusual when compared to past years (Fig. 6). The cooler air and water temperatures may have driven beachgoers to swim near river mouths and other outlets, where the water is much warmer.

Figure 6. Current related incidents on the Great Lakes by current type. For a description of each current type, visit Dangerouscurrents.org. GLCID, 2014.

Conditions Present During Current Related Incidents in 2014

Waves

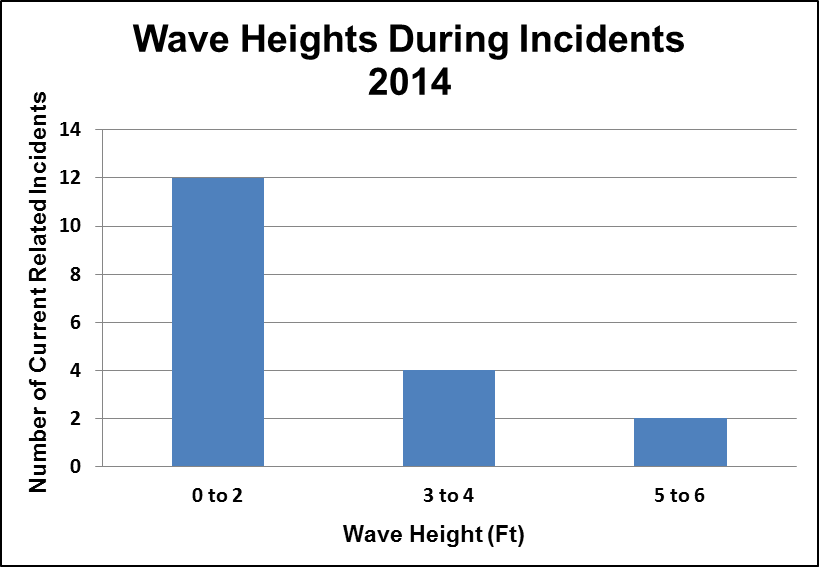

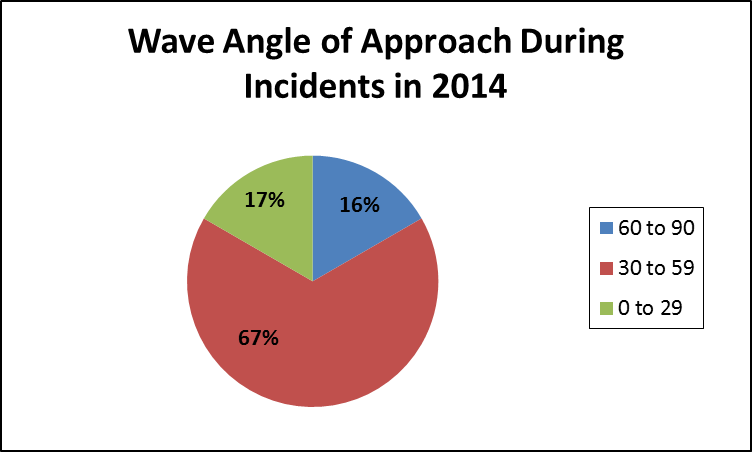

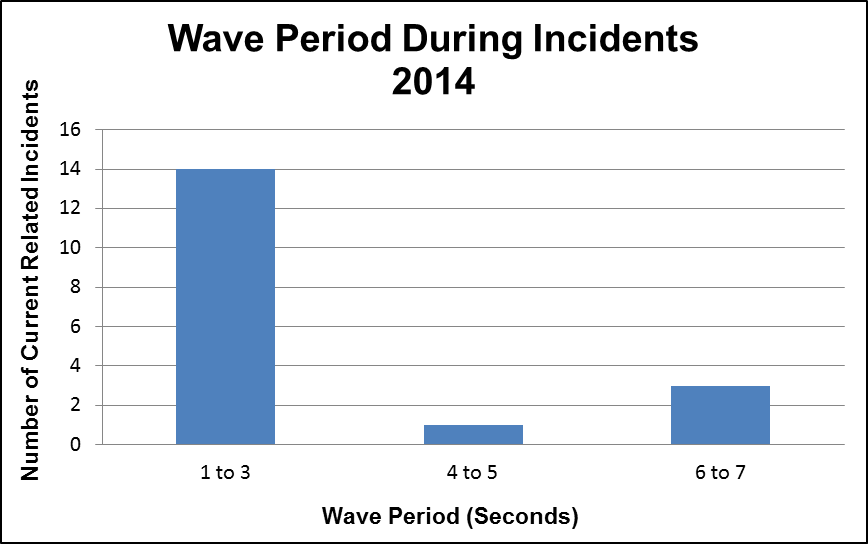

Most of the incidents on the Great Lakes occur when wave heights reach 3 to 5 feet (GLCID 2002-2013), however in 2014, incidents predominantly occurred under low wave height conditions (Fig. 7). During 67 percent of the incidents, waves were approaching the shoreline at a near 45 degree angle (Fig. 8), which is when the longshore current is theoretically strongest (USACE 1984). A stronger longshore current can lead to stronger structural currents near breakwalls and jetties, and it can join the outflow from a river, leading to stronger outlet currents (Shepard et al. 1941; Short 2007; Pattiaratchi et al. 2009; Leatherman 2011). Dangerous currents are most likely to occur with waves that have longer periods (Shepard et al., 1941; Leatherman 2003) because they feature longer wavelengths. A longer wavelength is associated with a larger volume of water, and a larger volume of water accumulating in the nearshore leads to the development of stronger currents. Current related incidents on the Great Lakes most often occur when wave periods are between 4 and 5 seconds (GLCID, 2002-2013). This year, however, a large number of incidents happened when wave periods were 3 seconds or less (Fig. 9). This is likely because the incidents in 2014 were primarily near shoreline structures and river outlets, which can act to “pile up” water in the nearshore and lead to a stronger current, despite lower wave heights and shorter wave periods.

Fig. 7. Wave Heights observed during current related incidents in 2014. GLCID, 2014

Fig. 8. Wave angle of approach relative to shore during current related incidents in 2014. GLCID, 2014.

Fig. 9. Wave period observed during current related incidents in 2014. GLCID, 2014.

Winds, Temperatures, and Weather Pattern

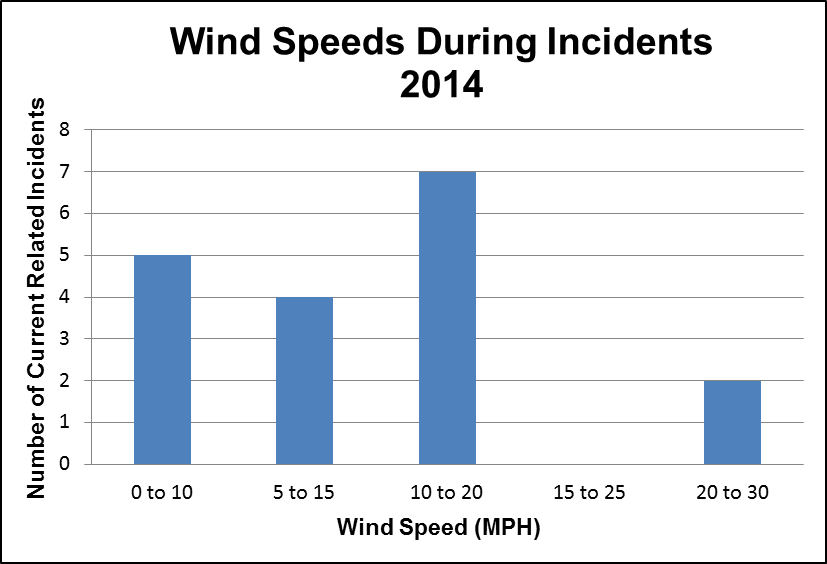

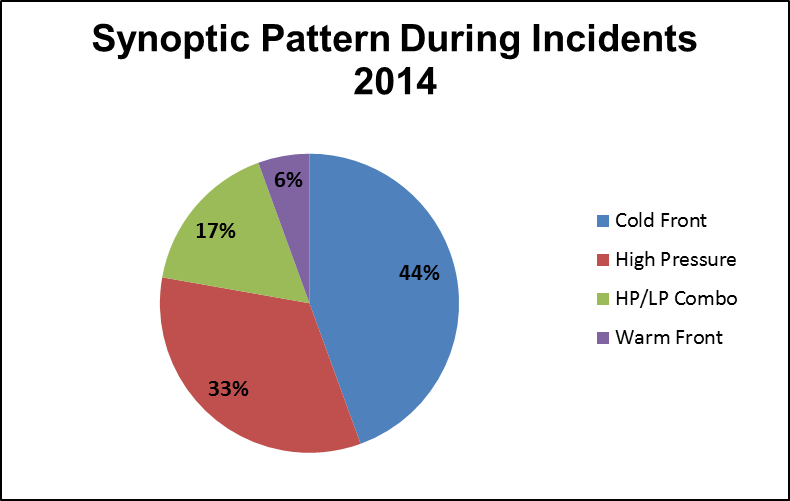

The bulk of the incidents in 2014 happened when wind speeds were 10 to 20 mph (Fig. 10), which is characteristic of current related incidents as a whole on the Great Lakes. However, there was an uncommonly high number of incidents that occurred when winds were fairly light (less than 10 mph), likely because many happened in areas less dependent on strong winds/high waves to develop currents, such as near shoreline structures and river outlets. Nearly half of the incidents occurred when a cold front was passing through the area (Fig. 11). This is unexceptional, as cold frontal passage is the predominant synoptic pattern observed during Great Lakes current related incidents collectively.

Fig. 10. Wind speeds observed during current related incidents in 2014. GLCID, 2014.

Fig. 11. Synoptic weather pattern during current related incidents on the Great Lakes. HP/LP Combo indicates that a combination of high pressure and low pressure systems were generating onshore flow at the time of the incident. For example, a high pressure system may have been exiting the area and a low pressure system moving towards the area, creating a tight pressure gradient between the two systems and over the site of the incident. GLCID, 2014.

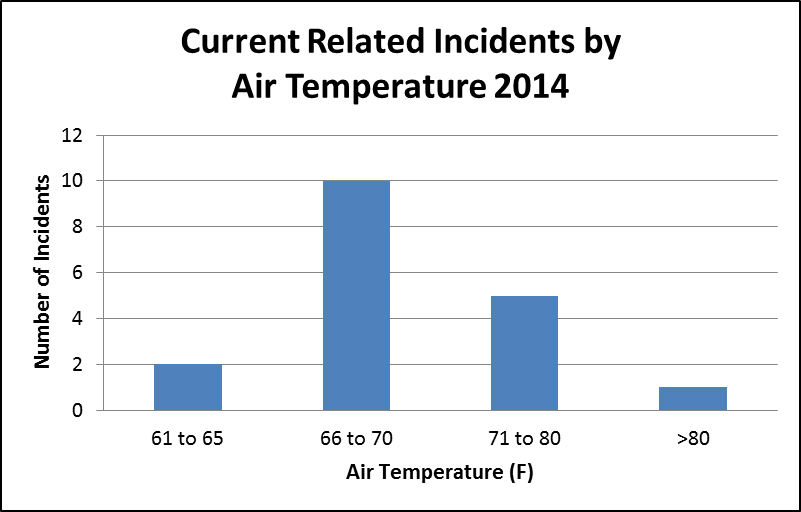

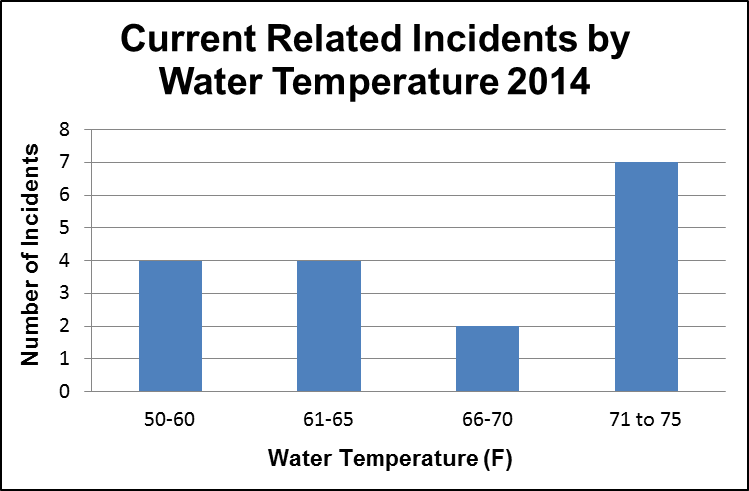

A better part of the incidents in 2014 occurred when the air temperature was warmer than 65 degrees (Fig. 12), which is representative of incidents on the Great Lakes (GLCID 2002-2013; Dodson 2013). Temperatures this season were much cooler than normal for the region, which may explain the spike in the 66 to 70 degree range (cooler than what one would expect for swimming conditions). However, many of the incidents occurred after the passage of a cold front, so it may have actually been warmer when the victims were swimming prior to the time of the incident. Water temperatures were also cooler than normal for 2014 (Fig. 2), so water temperatures during the incidents are also slightly cooler than expected (Fig. 13). Roughly half of the 2014 incidents occurred when water temperatures were colder than 65 degrees, so hypothermia likely played a part in causing the victims to struggle. Bear in mind that water temperature observations were taken from the observation platform nearest to the site of the incident, which may have been as far away as an offshore buoy. This could have skewed the water temperatures in Fig. 13 to be cooler than what they actually were at the site of the incident, especially for those that occurred near river outlets where water can be much warmer than the open lake.

Fig. 12. Current related incidents by air temperature. Most people swim once the temperature reaches above 65 degrees. GLCID, 2014.

Fig. 13. Current related incidents by water temperature. Water temperatures taken from the nearest observation site, which may have been an offshore buoy (cooler than what was likely in the nearshore where the incident occurred). GLCID, 2014.

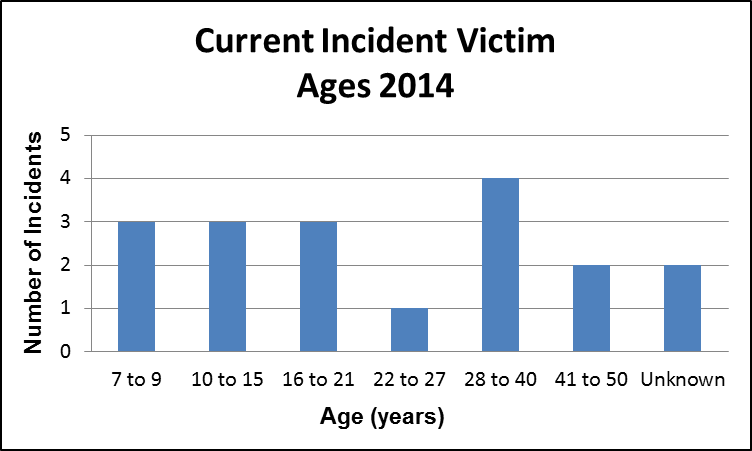

Victim Demographics

All but one of the 2014 victims were male, which is quintessential of drowning incidents across the U.S., including the Great Lakes region (Gensini and Ashley 2009; Paxton 2011; Howland et al. 1995, GLCID 2002-2013). The age of the 2014 victims ranged from 7 to 50 years, with most victims in the adolescent to young adult age groups (Fig. 14). This is not unusual, as a majority of the current incident victims on the Great Lakes are between the ages of 15 to 25 years or are parents attempting to rescue their children (GLCID 2002-2013). Hometown information was only known for 14 out of 18 incidents in 2014. Out of those, half lived within 60 miles of the beach, and half lived between 90 and 300 miles from the beach. Nearly all of the incidents occurred between noon and 8 p.m. LDT. There were three incidents that occurred around 9:30 a.m. LDT.

Fig. 14. Current incident victim ages from the 2014 swim season on the Great Lakes. GLCID, 2014

2014 Data Summary

Despite the cooler temperatures and lack of high-wave days, there were still a number of incidents near shoreline structures and river outlets. Swimmers should remember that dangerous currents are almost always present near these features-even during times of low waves and light winds, as was demonstrated this year. Moderate to high risk beach forecasts from the National Weather Service are focused on the conditions that will lead to especially hazardous currents, like those present during times of moderate to high waves and longer wave periods. A best practice is to swim near a lifeguard, and avoid the hazardous current-prone locations of breakwalls, piers, and river outlets.

Click HERE to see details on individual incidents from the database. If you know of or were involved in a current-related incident that is not in the database, fill out our incident submission form.

For references, click HERE.

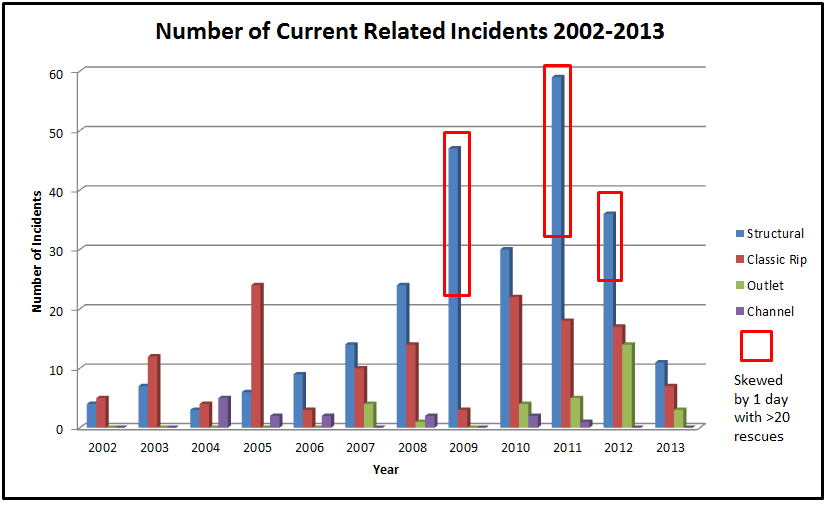

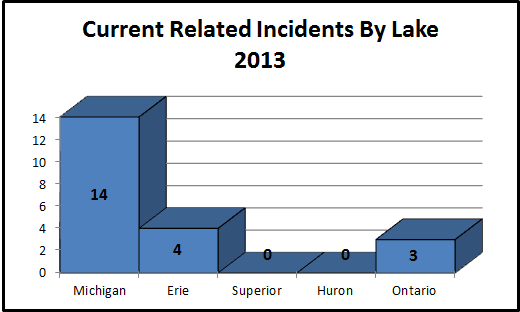

Overview

The number of current related rescues and drowning fatalities for summer 2013 fell below the Great Lakes average of 11 fatalities and 25 rescues per year (2002-2014 avg), with 7 fatalities and 14 rescues at least partially attributed to dangerous currents. Cool summer air temperatures and below average water temperatures likely kept most swimmers from venturing too far into the water, especially on high-swim risk days with northerly winds (waves are bigger and currents are stronger, yet temperatures are often cooler).

Fig. 1. Number of current related incidents 2002-2013. The years highlighted in red boxes each had 1 day where over 20 people were rescued. This skews the data, making it seem like the number of incidents is increasing with each year. General reporting of the incidents increased after 2005, when the NWS launched the rip current outreach campaign. Data also varies widely from year to year because the number of current related incidents depends on tourism, air and water temperatures, the number of moderate-high risk days, and even the number of cloudy vs sunny days. (GLCID, 2013).

Fig. 2. A majority of current related incidents occured on Lake Michigan in 2013 (GLCID, 2013)

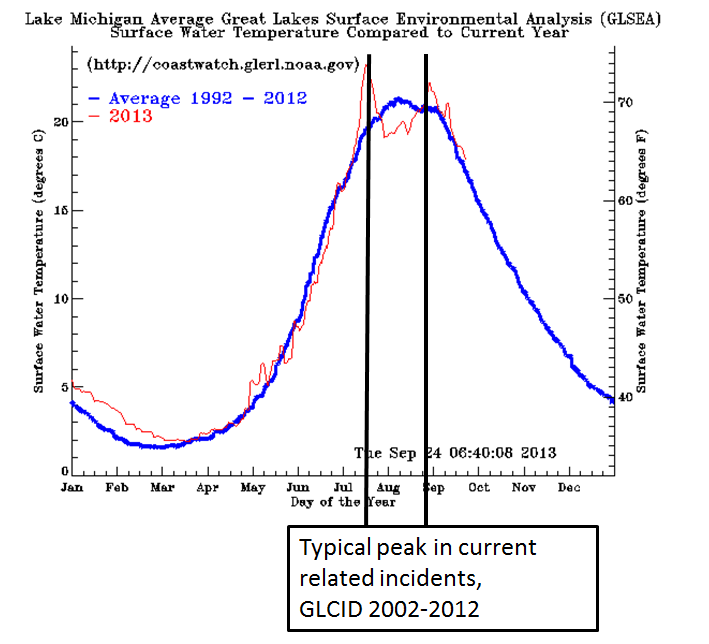

Current related incidents on the Great Lakes most often occur from late July into early August, as water temperatures, air temperatures, and tourism are at their peak. On Lake Michigan, where most current related incidents on the Great Lakes occur (Fig. 2), water temperatures were several degrees below normal for this time frame (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. 2013 Lake Michigan Water Temperatures vs. 1992-2012 normal (GLERL, 2013).

Additionally, air temperatures for July-August were below normal for the Great Lakes. In southwestern Lower Michigan, where a majority of the current related incidents occur, 2013 was the coldest summer since 2009 (See the NWS Grand Rapids Summer Climate Summary). This can be seen in the data as well (Fig. 1), with drowning fatalities and rescues at lows during those two years (with the exception of one high-rescue day in August 2009, which increases the number of rescues by 23).

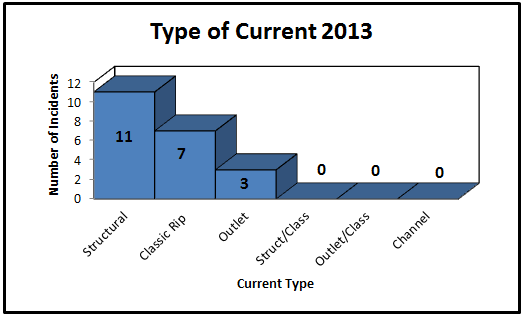

Type of Current

As is typical, a majority of the 2013 incidents on the Great Lakes were related to structural currents. These dangerous currents form near shoreline structures like piers, breakwalls, and peninsulas. For more information on the different types of currents on the Great Lakes, visit this webpage.

Fig. 4. All incidents in the GLCID were classified as either structural, classic rip , outlet, or channel currents. Incidents where it was not known where the victim was swimming at the time of the incident were classified as a combination (e.g. structural/classic would be a beach with a shoreline structure and properties of an intermediate beach type/sandbars). (GLCID, 2013).

Weather and Wave Conditions Observed During Current Related Incidents

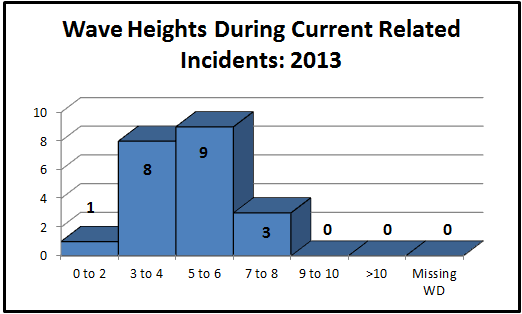

Wave Heights

Dangerous currents typically develop once waves reach 3-5 feet, except near shoreline structures or river mouths, where currents can be present at any time. In 2013, all but one incident occurred during wave heights of 3 feet or greater. The one incident where wave heights were less than 2 feet occurred near a shoreline structure. The National Weather Service had a high swim risk in effect with a Beach Hazards Statement during all of the 2013 incidents where applicable (some Great Lakes office's do not issue these products).

Fig. 5. Wave heights observed during current related incidents in 2013 (GLCID, 2013).

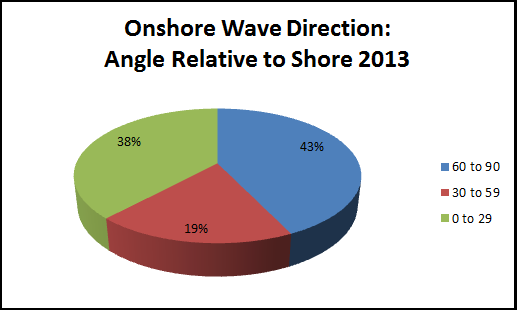

Wave Direction

Generally, classic rip currents are most likely when moderate to large waves approach the shoreline at a near-normal angle (near perpendicular). Structural currents, however, are more likely when waves approach the shoreline at more oblique angles to shore (45 degree angle is best).This trend was supported by the 2002-2013 GLCID data, seen in fig. 6. A majority of the incidents on the Great Lakes are due to shoreline structures, so one would expect a majority of the incidents to occur as waves approach the shoreline at an oblique angle.

Fig. 6. A majority of the incidents in 2013 occurred when the wave direction was at a near normal angle to shore (represented by 60-90 degreess). The remainder of the incidents in 2013 occurred under more oblique wave incidence angles (0 to 59 degrees relative to shore). Data from the GLCID, 2013.

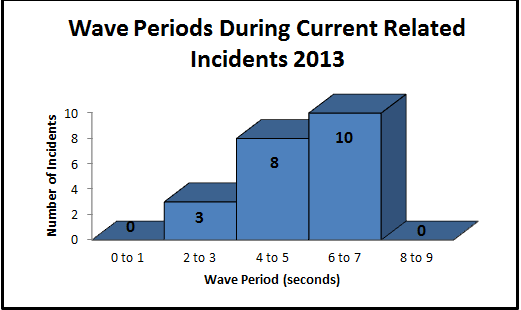

Wave Period

Wave periods (the time between each passing wave) during current related incidents on the Great Lakes typically fall between 4 and 5 seconds, which is classified as a "short period." Current-related incidents on the ocean are most often observed with longer wave periods, generally greater than 9 seconds. Short period waves add an additional hazard to swimmers, especially those caught in currents. Moderate to large waves crashing into the swimmer every 4 to 5 seconds can prevent them from completing the typical rip current-escape methods, like "flip, float, and follow" or "Swim parallel to shore." The shorter wave periods also create a more disorganized wave field, making rip currents tougher to spot on the Great Lakes (versus the ocean). In 2013, a majority of the current related incidents occurred with wave periods of 6 to 7 seconds (fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Wave periods observed during current related incidents in 2013 (GLCID, 2013).

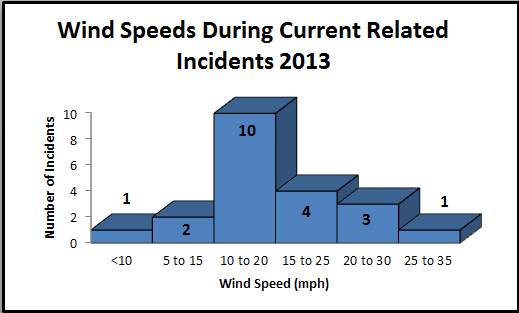

Wind Speed

Wind speed is an indirect factor in current development. Depending on the direction, strength, and longevity of the winds over the Great Lakes, moderate to high waves can be generated. When the waves approach the shoreline, they can lead to dangerous currents. Wind speeds during current related incidents in 2013 were primarily in the 10-20 mph range or greater. Only one incident in 2013 occurred with winds in the 0-10 mph category-and it was near a shoreline structure. Again, even when conditions appear benign, swimming near shoreline structures or river mouths is hazardous as currents exist with these features all the time.

Fig. 8. Wind speeds observed during current related incidents in 2013 (GLCID, 2013).

2013 Victim Demographics

As is typical of beach fatalities on the ocean and the Great Lakes, 52% of the victims were male and 33% were female. For 14% of the incidents, the gender of the victims was not known. The average age of the victims was 22 years old (only 11/21 cases had age information), and they lived an average of 35 miles from the location of the incident (only 12/21 of the cases had hometown information).

Case Study, 2013: Factors Come Together for a High Swim Risk Day

Late July into early August is when current related incidents on the Great Lakes peak, mainly due to the combination of warm water temperatures, warm air temperatures, and the high number of vacationers. July 19th was the perfect set up for high swim risk conditions, with water temperatures on Lake Michigan in the 70s and air temperatures along the western Michigan coastline in the 80s. By mid afternoon, a cold front was situated just west of Lake Michigan, so winds over the lake were out of the south-southwest. Waves that day were 3 to 6 feet, also out of the south-southwest, with a wave period of 6 seconds. South-southwest wind/wave directions typically lead to the development of a strong longshore current on the eastern shores of Lake Michigan, which can intersect a breakwall and move lakeward as a structural current. Though structural currents are the most likely of the beach hazards on the eastern Lake Michigan shoreline during south-southwesterly winds, classic rip currents are also possible. Typically, classic rip currents form under shore-normal wave incidence (at a 60-90 degree angle from shore) but they can also form under more oblique incidence (0-59 degrees), which makes the rip current circulations more diagonal (versus moving directly outward from shore). As a result, the National Weather Service in Grand Rapids, Michigan issued a Beach Hazards Statement (around 4 am the 19th), citing that waves would be high, structural currents would form on the south sides of breakwalls, and classic rip currents were possible. Overall, the swim risk was high, and people were encouraged to steer clear from the lake.

Fig. 9. Surface map from the Weather Prediction Center at 2:00 PM EDT on July 19, 2013, just prior to the first set of incidents. The times surrounding the passage of a cold front are responsible for a majority of current related incidents on the Great Lakes (GLCID, 2013).

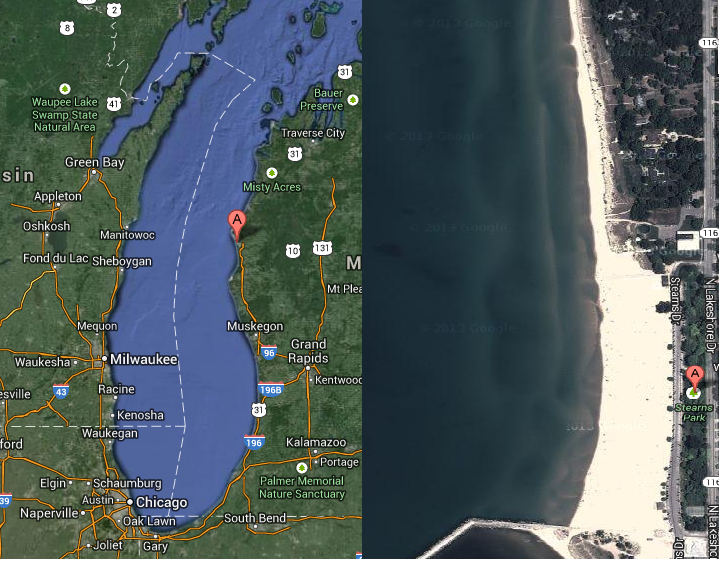

Around 3 pm EDT, six people had to be rescued from classic rip currents off Stearns State Park, near Ludington, Michigan (Fig. 9). Surfers at the beach made several observations of rip currents that afternoon. They reported that the rip currents were developing after larger sets of waves, moving offshore at an angle, primarily towards the northwest. They also reported a strong longshore current. After two hours of prime surf time, they heard the cry of struggling swimmers within the swimming area at Stearns Park. Luckily, despite the strong currents and waves, they were able to rescue them.

Fig. 10. Stearns State Park, Mason County, MI. Images from Google, 2013. Note the complex sandbars, the darker areas representing old rip current channels. The swimmers were rescued at the northern end of the designated swim area (away from the breakwall to the south).

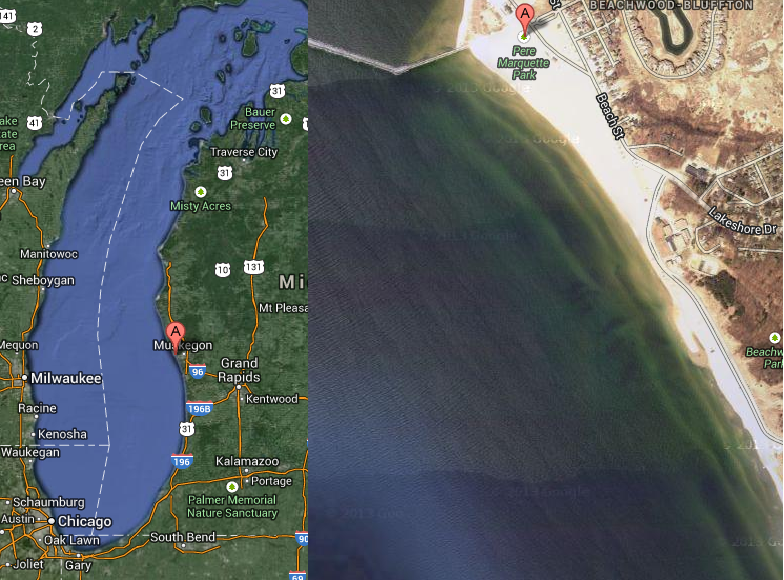

Later that evening, around 7:30 PM EDT two additional incidents occurred. Two sisters were swimming near the south side of the breakwall at Pere Marquette Park in Muskegon, Michigan when they were caught in a structural current. The younger sister recounted, "we weren't too far from shore when the current began to pull us out further into the lake. We both began to struggle and began grabbing onto each other before being separated." The young girl then told authorities that she lost sight of her sister as she struggled in the waves. Luckily, the younger sister was rescued by a 20 year old woman. Unfortunately, her sister wasn't recovered until the 21st of July.

Fig.11. Pere Marquette Park, Muskegon Michigan. Images from Google, 2013. The victims in this case were swimming on the south side of the breakwall when they were caught in a structural current.

Concluding Remarks

This data was collected by the National Weather Service in Marquette, Michigan. All incidents in the database were at least partially due to a dangerous current. Many of the incidents are likely a combination of currents and high, short period waves. All readers are encouraged to read about how the data is collected here. These numbers must be viewed relative to the number of people that visit these beaches each year, which is on the order of millions.

Click HERE to see details on individual incidents from the database. If you know of or were involved in a current-related incident that is not in the database, fill out our incident submission form.

For references, click HERE.

Overview

This year was slightly above average for Great Lakes current-related incidents when compared to the average of 11 current related fatalities per year (2002-2014, Great Lakes Current Incident Database). As is often the case, Lake Michigan was responsible for a majority of the incidents, with its eastern shores favorably aligned to the prevailing wind flow and its popularity with tourists. In the Great Lakes, channel current incidents occur on average once per year. This year, there were no channel current incidents reported.

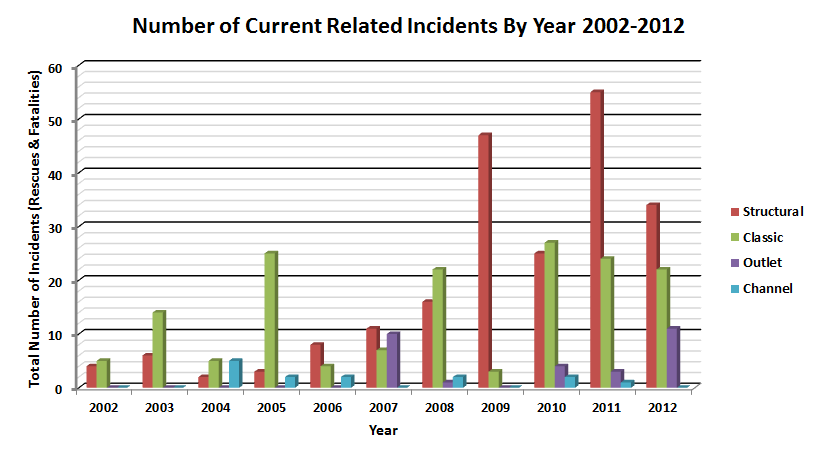

Fig. 1. Current-related incidents across the Great Lakes, 2002-2012. Data from the GLCID, 2012.

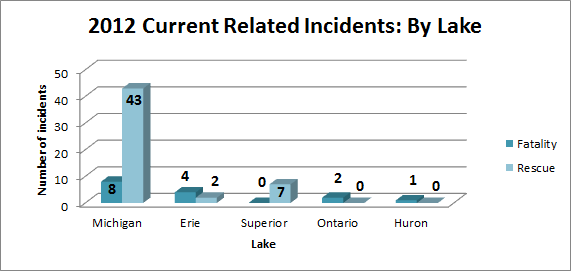

Fig. 2. 2012 current related incidents, sorted by lake. Data is from the GLCID, 2012.

About The Victims

As is typical of current-related incidents on the ocean (and of the Great Lakes), most of the victims were male. Out of the 67 total incidents in the database for 2012, 25 of them were male and 19 were female. For 23 of the incidents, the gender of the victim was unknown. The average age of the victims this year was 22 years old, which is also common in current related incidents. Approximately 60% of the victims this year were locals to the beach at which they drowned or were rescued at. In the GLCID, local is defined as living within 30 miles of the beach.

Conditions Observed During 2012 Current-Related Incidents

Wind Speeds

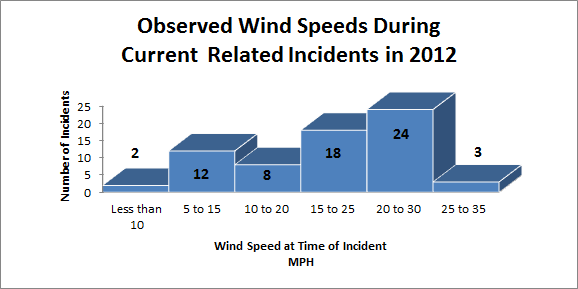

The most commonly observed wind speed classification during the 2012 incidents was 20 to 30 mph. Strong southerly winds commonly lead to beach problems, as they typically bring warmer temperatures and pleasant weather in combination with moderate to high waves. In addition, a large number of beaches on Lake Michigan's eastern coast have break walls that extend east to west into the lake.

Fig. 3. Wind speeds observed during the current related incidents of 2012. Most incidents occurred when winds were in the 20 to 30 mph range. Data from the GLCID, 2012.

Wave Heights

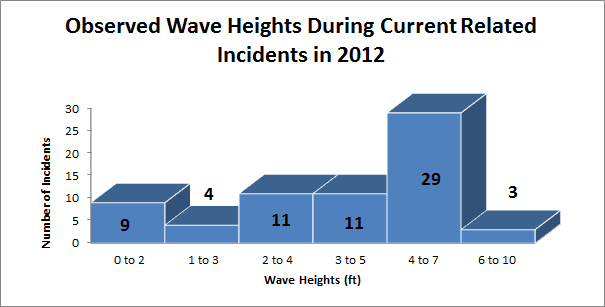

On the ocean and in the Great Lakes, higher waves lead to dangerous current development. This can also been seen in the 2012 GLCID wave data. Most incidents this year occurred when waves were in the 4 to 7 ft. range. There were 9 incidents that occurred when waves were 2 feet or less, and 7 of those incidents were outlet currents.

Fig. 4. Wave heights observed during current-related incidents are shown above. A majority of the incidents occurred when wave heights were greater than 2 feet. Data from the GLCID, 2012.

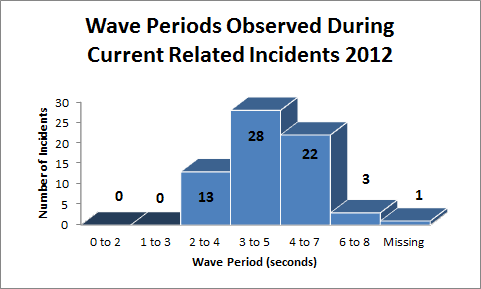

Wave Periods

Most of the incidents occurred when waves had a period between 3 and 5 seconds. This is one area where rip currents on the ocean are different from rip currents on the Great Lakes. Typically, rip currents in the ocean occur during longer wave periods, which is actually defined as longer than 9 seconds. Only 3 incidents occurred when the wave period reached close to 'long period' criteria, at 6 to 8 seconds. This generally shorter wave period (mostly 3 to 5 seconds) results in an additional hazard to the rip currents-as most people cannot recover while fighting a current and these rapidly incoming high waves.

Fig. 5. Wave periods observed during current-related Incidents in 2012. Most of the incidents occurred with wave periods in the 3 to 5 second ranges. Data from the GLCID, 2012.

Most Hazardous Day of 2012:

August 5, 2012: 6 Current Related Fatalities, 7 Current Related Rescues (13 total incidents)

On this particular day, a low pressure system moving from northern Ontario into Hudson Bay brought two cold fronts across the Great Lakes. In addition, high pressure approaching from the plains extended a ridge across the region. This brought strong southerly, westerly, and northwesterly winds of 15 to 25 mph to the Great Lakes region throughout the day. These winds generated wave heights of 3 to 7 feet. NWS offices around the Great Lakes know this pattern is hazardous for beachgoers, so areas along the shoreline had a moderate to high risk of dangerous currents and waves in effect, and general statements about the hazards associated with high surf.

Archived Surface Analysis

Fig. 6. Weather Map at 2:00 PM EDT from the Weather Prediction Center on August 5, 2012.

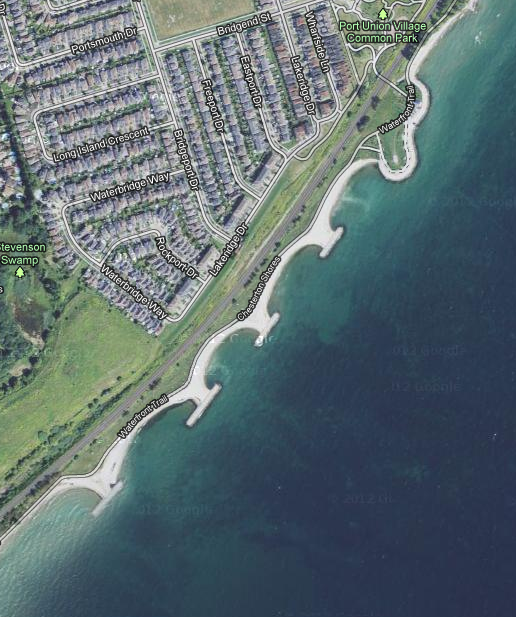

By the end of the day, there was a total of 13 current-related incidents. There were two incidents that occurred on Lake Ontario around 8:30 am at a beach where there was a breakwall and complex sandbar features. It is unknown whether the victims were swimming at the breakwall or not, however the wind/wave direction was directly onshore (out of the south, ahead of the front).

Fig. 7. Beach where the two men drowned from a current in Scarborough, Canada on Lake Ontario.

Image from Googlemaps, 2012.

Later that morning and into the early afternoon time frame, winds on southern Lake Michigan were out of the northwest at 15 to 25 mph, with waves in the 4 to 7 ft range. This set the stage for two current-related drownings and two rescues along the southeastern shores of the Lake, when a man noticed two children in distress from the current and jumped in to rescue them. The children survived, but the man did not. For this particular instance, it was not known whether the victims were caught in the river outlet at the beach or a rip current that developed within the sandbars.

Fig. 8. Cherry Beach, in Chickaming Twp, Berrien County, MI. It was not known whether the victims were caught in the outlet current near the river mouth or a rip current associated within the sandbars. Googlemaps, 2012.

During that same afternoon, a little bit farther down the beach, another man drowned at Tiscornia Beach near St. Joseph, MI. It was not said if the man was swimming near the breakwall at the beach, however he was caught in a current and began to struggle. Two people tried to rescue him, however they could not due to the strong current.

Fig. 9. Tiscornia Park, in Berrien County, MI. A man drowned when he was caught in a dangerous current in the early afternoon. Googlemaps, 2012.

Farther north on Lake Michigan, six people got into trouble with rip currents. One man drowned while trying to save his nephew from a rip current at Peterson Beach, Benzie County MI. He was swimming with 3 family members, who barely escaped the current themselves. Just prior to this incident, another woman and her granddaughter were caught in another rip current at the same beach, and nearly drowned but were rescued by several beach bystanders. Winds were westerly at approximately 10 to 20 mph, with waves in the 3 to 5 ft range. These onshore winds and waves led to the perfect set up for classic rip currents. Old rip current channels can be seen at this beach in the Googlemaps satellite image below.

Fig. 10. Peterson Beach in Benzie, County MI. Darker areas on the image show old rip current channels. This was the site of 6 rip current incidents this summer.

Googlemaps, 2012.

Lastly, another man drowned on Lake Erie at Long Point Provincial Park, Ontario Canada. The 43 year old man was swimming in the park with his two children around 4 pm when he began to struggle in the water. Two witnesses jumped in to help but reported that the rip current was too strong, and they could not reach him.

Fig. 11. Notice the sandbars running parallel to the shore at Long Point Provincial Park, Ontario. This helps to trap water near the shore, leading to rip current development during times of moderate to high surf. Image from Googlemaps, 2012.

Conclusion

In summary, 2012 was a slightly above average year for current-related incidents on the Great Lakes. Remember to pay attention to beach signs and forecasts before going out to enjoy the Great Lakes next summer.

Click HERE to see details on individual incidents from the database. If you know of or were involved in a current-related incident that is not in the database, fill out our incident submission form.

For references, click HERE.

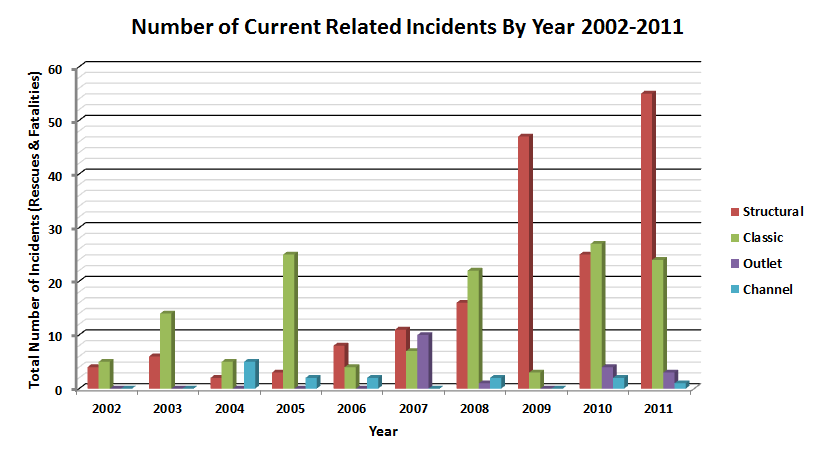

Overview

The number of current related incidents on the Great Lakes this swim season was above the average of 11 fatalities per year (GLCID, 2002-2014). This year there 15 drowning fatalities, with a majority of them on Lake Michigan. In addition, the Great Lakes saw at least 68 rescues. This is higher than any year (even last year), though it is likely a function of increased media attention and coverage of current related incidents.

Current related incidents from 2002-2011.

As is typical, Lake Michigan had the majority of the incidents, with 60 reported rescues and 10 drowning fatalities related to dangerous currents. There were more incidents in Lake Ontario than is typical, likely due to increased media attention to dangerous currents. Incidents in the past were likely underreported, with only 1 drowning and 1 rescue attributed to dangerous currents in the database prior to this year. This year there were 3 deaths and 1 rescue.

Fig. 1. Number of current related incidents by Lake 2002-2011. Lake Michigan had the highest number of

drowning deaths and rescues due to dangerous currents. GLCID, 2011.

Dangerous currents occur near shoreline structures, river mouths, and within sandbars-especially during high waves. Figure 2 below shows beaches where some of this years incidents occurred.

Fig. 2. Beaches where some of this summer's incidents occurred.

Images from Googlemaps.com.

Conditions Observed During and Prior To Current-Related Incidents

Wave heights

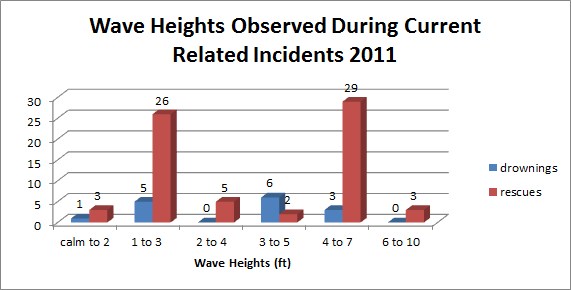

Most of the incidents took place under moderate to high wave events (i.e higher than 3 feet). From 2002-2010, most of the incidents occurred when waves ranged from 2 to 4 feet. This year, it seemed most incidents were in the 1 to 3 feet and 4 to 7 feet ranges. This is because a majority of the incidents this year occurred near shoreline structures. Structural currents can occur with smaller wave heights, like the 1 to 3 feet range. Only four incidents had waves in the calm to 2 feet range, and two of them were associated with breakwalls.

Fig. 3. The graph above shows the wave heights during each death/rescue incident. Most of the incidents

occurred under the 4 to7 ft range and the 1 to 3 ft range. GLCID 2011.

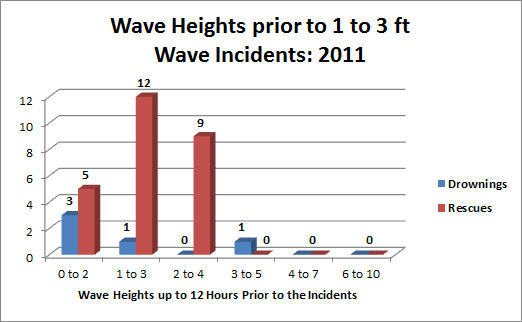

In contrast to previous years, current related incidents often occurred as wave heights were increasing (i.e they had lower wave heights up to 12 hours prior to the incident). Most of the current-related incidents in the past occurred as wave heights were decreasing or when wave heights were relatively steady through the day.

Fig. 4. Most wave heights prior to 1 to 3 feet range incidents were still in the 1 to 3 feet height range

before the incident. Data from the GLCID, 2011.

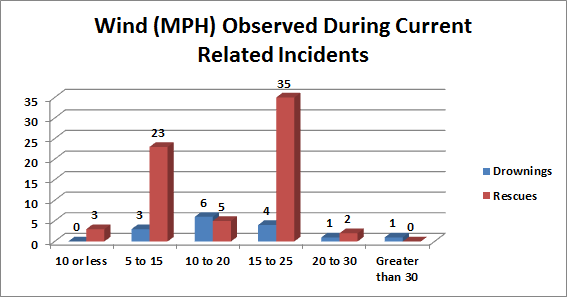

Wind Speeds

Observed wind speeds from the time of the incident most often ranged from 15 to 25 mph. The secondary spike in the 5 to 15 miles per hour range was a result of the large number of structural current incidents.

Fig. 5. Observed winds at the time of the incidents.GLCID, 2011

Victim Demographics

Gender

As is typical in drowning rescue and fatality data across the globe, 83% of the victims involved in the incidents were male (17% were female, and for 33% the gender was unknown). The average age of the victims was 22 years old, which is also typical of current related incidents.

Most Noteable Case from 2011

August 3, 2011: 1 Drowning Fatality and 28 Rescues Attributed to Dangerous Currents

Location: Holland, MI (Ottawa County) and Pentwater, MI (Oceana County).

On this day, over 30 rescues were made by the Coast Guard located in Ottawa, MI. Out of the 30 total rescues at Holland State Park, 28 were related to structural currents. The other two were related to personal watercraft. Another girl in Pentwater, MI (north of Holland) drowned when she was swept out into the lake by a structural current near the breakwall.

Fig. 6. Holland State Park (Ottawa, MI). Structural current was on the north side of the pier. Image from Google Maps (2011).

The night before, a cold front had swept across Lake Michigan, and high pressure was moving in from the west. As a result, winds were 15 to 25 miles per hour out of the northwest. Knowing this to be a typical set up for strong current development, the National Weather Service in Grand Rapids, MI had a high swim risk posted on their web page. The beaches were crowded, with mostly sunny skies and temperatures in the upper seventies and low eighties. At Holland State Park, the red flags were flying, warning swimmers to stay out of the water. No doubt, park officials recalled a similar day in 2009, where in a five hour period; 23 people had to be rescued near the north pier. Conditions on that day were almost the same as August 3, with winds 15 to 25 miles per hour out of the northwest and waves in the 2 to 5 feet range.

Fig. 7. Hydrologic Prediction Center (HPC) weather map from 2:00 PM EDT on August 3, 2011.

High pressure is seen to the west, and the cold front to the south east.

By 8:00 PM EDT that evening, the Department of Natural Resource staff closed the beach due to the high number of rescues. As winds were northwest, the longshore current moved parallel to the beach in a southerly direction, intersecting piers on the north sides and jetting out into the lake as a structural current. One rescued girl told NWS Marquette in an interview, "We were not swimming near the pier, but we got pulled towards it because of the current (longshore current). We were to the right [north] of Holland State Park Beach. We were just behind the buoys that mark the spot where swimming is prohibited, when we were pulled out further into the lake along the breakwall (Structural current)." When asked which was the most prohibitive to her swimming (or getting back to shore), the waves or the current, she replied, "The current was the worst. Hands down."

Fig. 8. Photo of the North Pier at Holland State Park, Ottawa county, MI. This photo was not taken August 3, 2011.

Photo released at: https://home.waycom.com/PhotoByDan/Default.htm.

Further north up the beach, there was another rescue. A 13 year old girl was caught up in the structural current along the northern pier near Charles Mears State Park. She went under, but a 29 year old man from Newaygo, MI was able to reach her. A few days later, the girl died at a hospital in Grand Rapids, MI. Conditions were slightly different than at Holland, with northwest winds at 10 to 20 miles per hour, though for the evening prior to the incident, the winds were 15 to 25 miles per hour. Waves ranged from 3 to 5 feet at the time of the incident (using the northern Lake Michigan Buoy). At the beach, witnesses indicated that the waves may have been more like 6 to 8 feet.

Fig. 9. Beach at Charles Mears State Park, Pentwater, MI (Oceana County). Photo from Googlemaps.com.

Channel Current Drowning Fatality

July 26, 2011: 7 year old boy drowns at Barracks Beach, Presque Isle

Location: Presque Isle (Barracks Beach) in Erie, Pennsylvania

Fig. 10. Presque Isle, Erie Pennsylvania: The channel current at Barracks beach played a part in the death of a 7 yr old boy.

Image from Googlemaps.com

A 7 year old boy went ahead of his parents and into Lake Erie with his siblings for a swim around 9:00 PM EDT. A short time later, the boy could not be found. The head lifeguard (not present during the event) said what likely happened was the boy went into the water and was pushed off the sandbar. He also mentioned that once winds get above 10 miles per hour, the current in that location picks up and people usually start to struggle to stay on the sandbars. That night, winds were west at 15 to 25 miles per hour and waves were in the 1 to 3 feet range. According to the Lake Erie Buoy, the mean wave direction was out of the north, likely allowing for strong currents to move through that general beach. The lifeguard added, "If the beach had been open later, it would have been a yellow flag day. Those currents likely contributed to the death of the boy."

Fig. 11. The left image was taken from the Presque Isle Lifeguard Manager Steve Dunsmore, explaining how the channel currents

work in that area, which is similar to the diagram from Michigan SeaGrant (right).

Summary:

This year we had 83 incidents related to dangerous currents. 15 of the 83 incidents were fatalities. Overall, it was an above average year, though it did not compare to the 30 current related drowning deaths across the Great Lakes in 2010.

Click HERE to see details on individual incidents from the database. If you know of or were involved in a current-related incident that is not in the database, fill out our incident submission form.

For references, click HERE.

Overview

2015 was another below average year for current-related rescues and fatalities. Six fatalities and nine rescues were confirmed, for a total of fifteen incidents. Unfortunately, a variety of factors can play a role in the number of current-related incidents that occur each year.As a result, we can only speculate as to why incidents this year were below the average of 12 fatalities and 23 rescues.

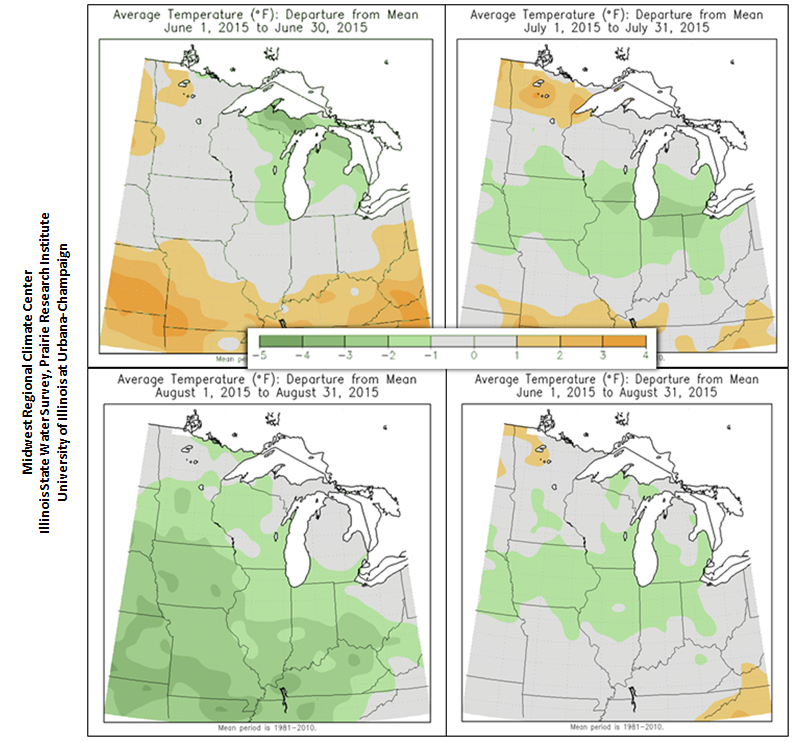

This swim season was marked by average air temperatures or slightly below the mean, and near normal water temperatures on Lake Michigan. Precipitation was near or slightly above normal for the summer season in many locations along the Great Lakes shoreline. Generally, when air and water temperatures are cooler, less people venture into the water for a swim (this was likely the case in 2013, 2014). Since conditions were near average for this season, this may not have had a large impact on the number of incidents.

Fig. 1. Graph depicting the number of current-related incidents (rescues and fatalities) each year. The gold boxes represent single days with greater than 18 rescues in one location. These can make it look like incidents were increasing dramatically, even though they were just rare examples of 'perfect storm' conditions for dangerous currents. In recent years, incidents have been below the average, GLCID (2015).

Fig. 2. Graphs from the Midwest Regional Climate Center (MRCC) showing how this summer the temperatures were slightly below the mean.

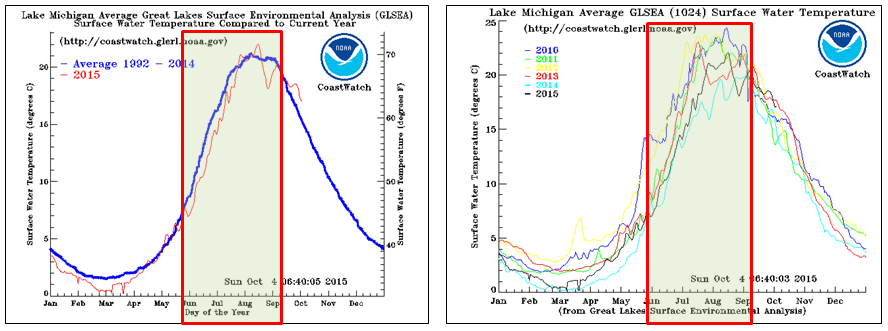

Fig. 3. Graphs of Lake Michigan average water temperatures compared to long-term averages (left) and Lake Michigan average water temperatures from 2010-2015 (right). Data from GLERL statistics page.

Increased Beach Safety

Recent improvements in beach safety practices may be a factor in the below normal number of incidents in recent years, though this is impossible to measure using the incident statistics. Since 2013, new water safety task force groups developed to address beach safety issues in local areas, and there have been several grant efforts focused on improving the availability of beach rescue equipment and Great Lakes-specific beach hazards outreach and education.

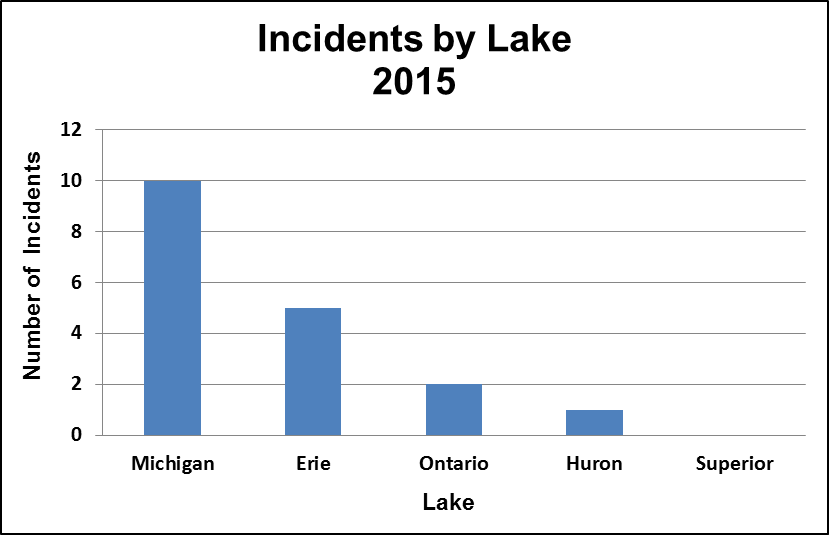

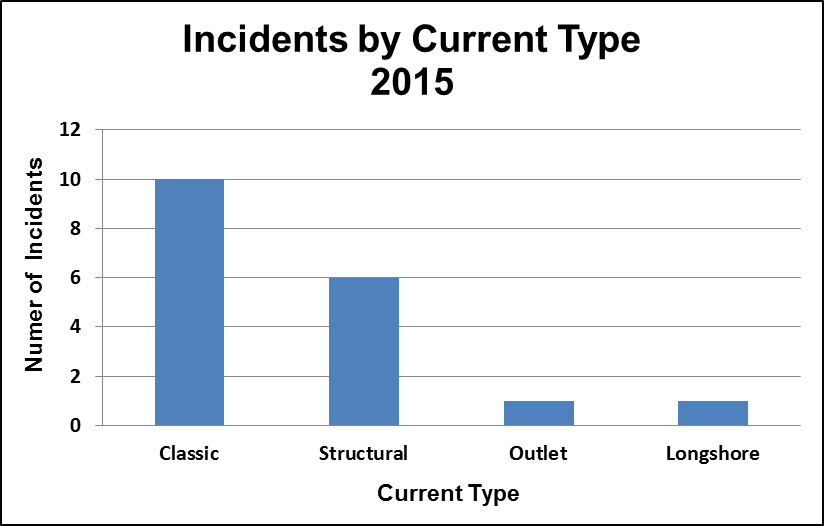

Where the Incidents Occurred

Most of the incidents occurred on Lake Michigan and Lake Erie, as is typical. This year, however, it appears classic rip currents were responsible for a majority of the incidents. This differs from previous years where most of the incidents were a result of structural currents.Conditions may have been more favorable for classic rip current development this year than in past years. It also depends on where people are swimming, so it is possible there were less people swimming near piers, breakwalls, and other shoreline structures.

Fig. 4. Graph of Current-Related Incidents by Lake(GLCID, 2015).

Fig. 5. Graph of Current-Related Incidents by Current Type. This year, there were more classic rip current incidents (Classic) than structural, outlet, or longshore currents (GLCID, 2015). There were no channel current incidents this year.

Weather and Wave Conditions During Current-Related Incidents

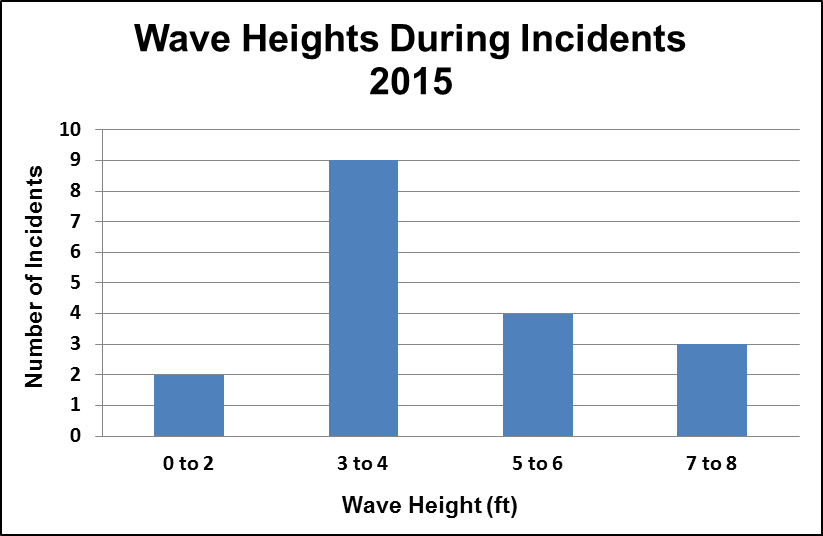

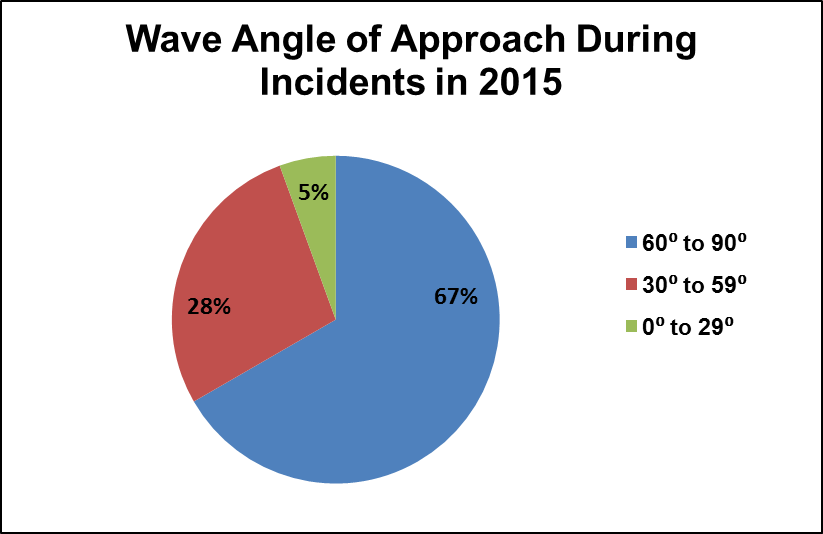

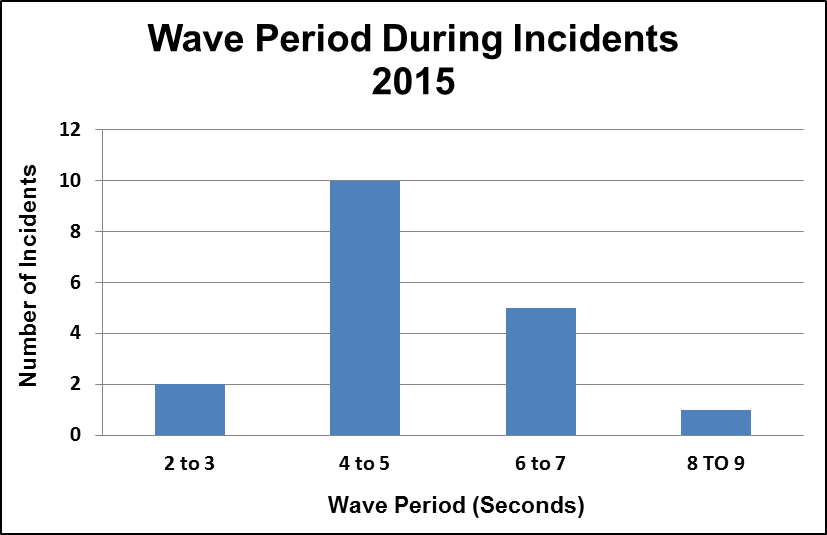

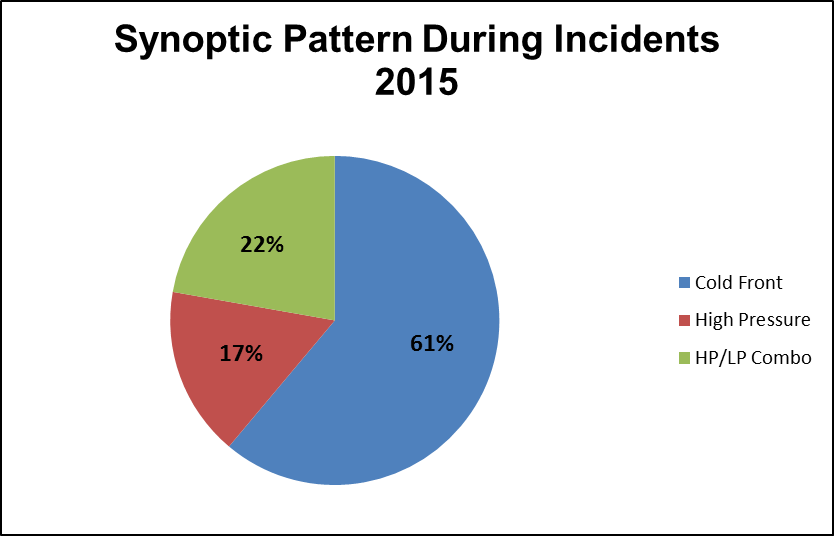

Dangerous currents develop when water 'piles up' near the beach (Shepard et al. 1941, Shepard and Inman 1950; Munk 1949). Water 'piles up' near the beach when waves are moderate to large in height, have longer periods (time in between each wave), and approach the shore at more direct (perpendicular) angles. This year, conditions during the incidents were supportive of classic rip current development. In 80% of the 2015 cases, the waves approached the shoreline at near-perpendicular (60 to 90 degree) angles. Wave heights during 73% of the cases were greater than three feet, and at times had longer wave periods of 6 to 7 seconds. A majority of incidents occurred surrounding the passage of a cold front, which is typical of current-related incidents on the Great Lakes as a whole (GLCID, 2002-2014).

Fig. 6. Graph of wave heights during the 2015 incidents.(GLCID, 2015).

Fig. 7. Graph of the wave angles of approach relative to shore during current related incidents in 2015. Direct approaches were classified as within 30 degrees of perpendicular (or 60 to 90 degrees relative to shore). Near parallel approaches were classified as approaching the beach between 0 and 29 degrees. (GLCID, 2015).

Fig. 8. Graph of Wave Periods during Current-Related Incidents. The average wave period on the Great Lakes is around 4 seconds, which is why the majority of incidents in 2015 saw wave periods in the 4 to 5 second category (GLCID, 2015).

Fig. 9. Graph depicting the broader-scale (synoptic) weather pattern during current-related incidents in 2015. A majority of incidents occur surrounding the time of a cold front passage. HP/LP combination means that onshore flow was created within the gradient between high/low pressure systems, and that no real front was present nearby(GLCID, 2015).

Victim Demographics

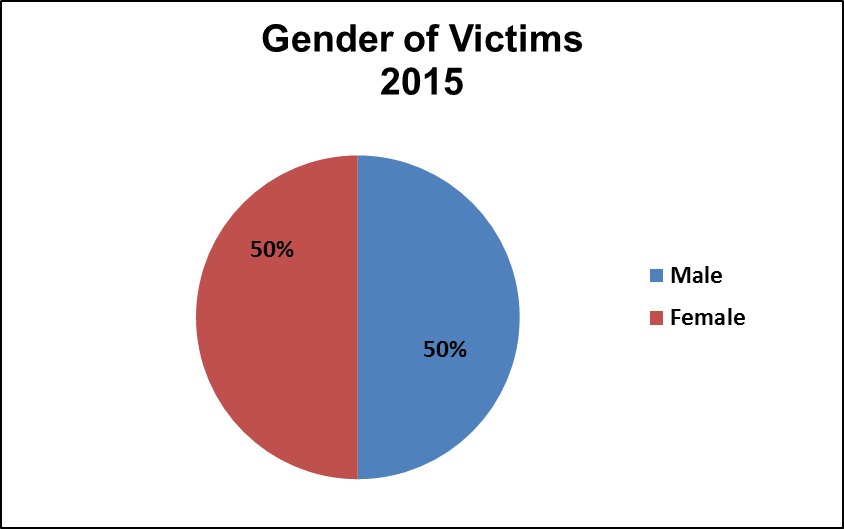

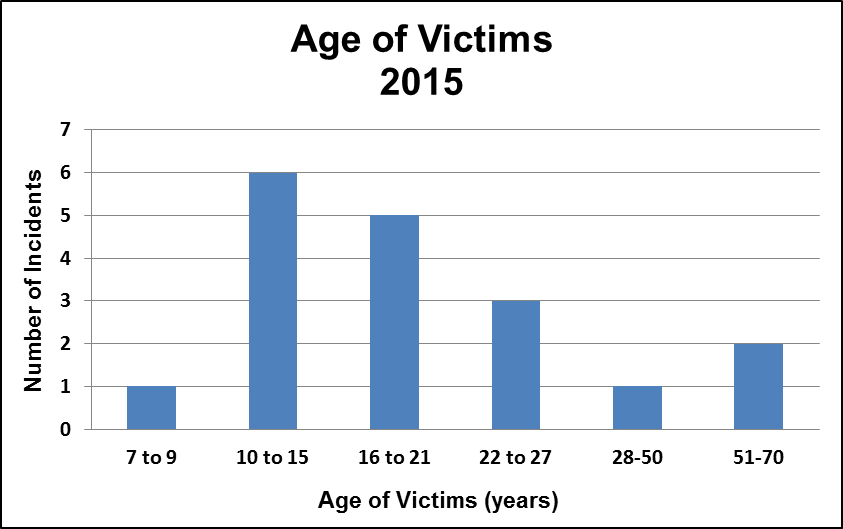

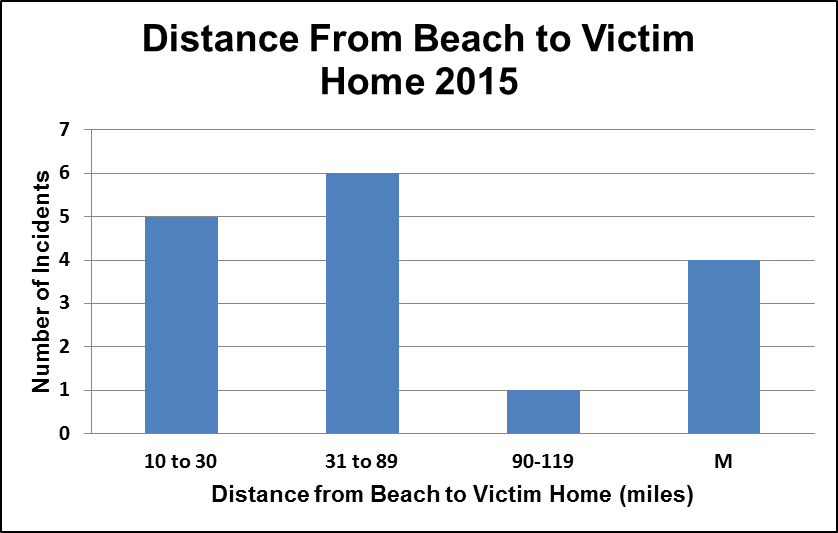

Normally, victims involved in current-related incidents are male because they are more likely to engage in risky behavior (Houser et al. 2011; Howland et al. 1996; Baker et al., 1992; Rowan et al., 2004). From 2002-2014, 70% of the victims were male. This year was an unusual split of male and female victims. As is typical, most of these victims were adolescent or young adults between the ages of 10 and 27. All but one of the victims lived within 90 miles of the beach where the rescue or fatality occurred, which is comparable to the 2002-2014 GLCID data.

Fig. 10. Graph depicting the gender of victims involved in current-related incidents(GLCID, 2015).

Fig. 11. Graph depicting the age of victims involved in current-related incidents(GLCID, 2015).

Fig. 12. Graph depicting how far each victim lived from the beach where the incident occurred. Most victims in 2015 lived within 90 miles of the beach where they drowned or were rescued at(GLCID, 2015).

Closing Thoughts

Overall, the 2015 swim season was below average in the number of current-related rescues and fatalities. This may have been because of the slightly below normal average high temperatures, slightly cooler water temperatures, near to above normal precipitation, or improvements in beach safety and education. To view the data from the Great Lakes current incident database, visit www.dangerouscurrents.org and click on "Incident Database."

Unfortunately, there were 8 rescues that occurred in Michigan where critical information, such as time and location, were unavailable. These may be added into the database at a later date if the details can be confirmed. There were also rescues that occurred in Ontario this year that have yet to be confirmed. These rescues will be added in at a later date once the details become available.

Click HERE to see details on individual incidents from the database. If you know of or were involved in a current-related incident that is not in the database, fill out our incident submission form.

For references, click HERE.

Overview

Current related rescues and fatalities were slightly above average for the 2016 swim season, with 16 fatalities and 34 rescues (two still in critical condition as of 12/22/17). The ten-year average from the Great Lakes Current Incident Database (GLCID) is 12 fatalities and 23 rescues per year (2002-2011). This is in contrast to the previous three years, where we've seen below average numbers (Fig. 1) due to cooler air and water temperatures and improved beach safety measures. Drowning fatalities due to other water safety concerns, like boating, waves, and pier washes were also higher than normal this year, according to the Great Lakes Surf Rescue Project.

Fig. 1. Number of Current-Related Incidents by year (2002-2016). 2016 was slightly above the average of 12 fatalities and 23 rescues per year (GLCID, 2016).

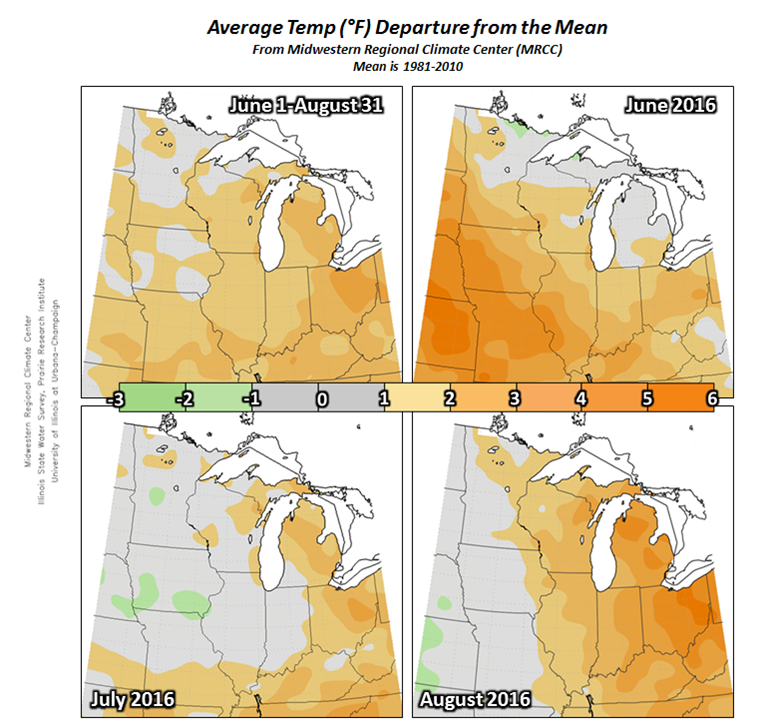

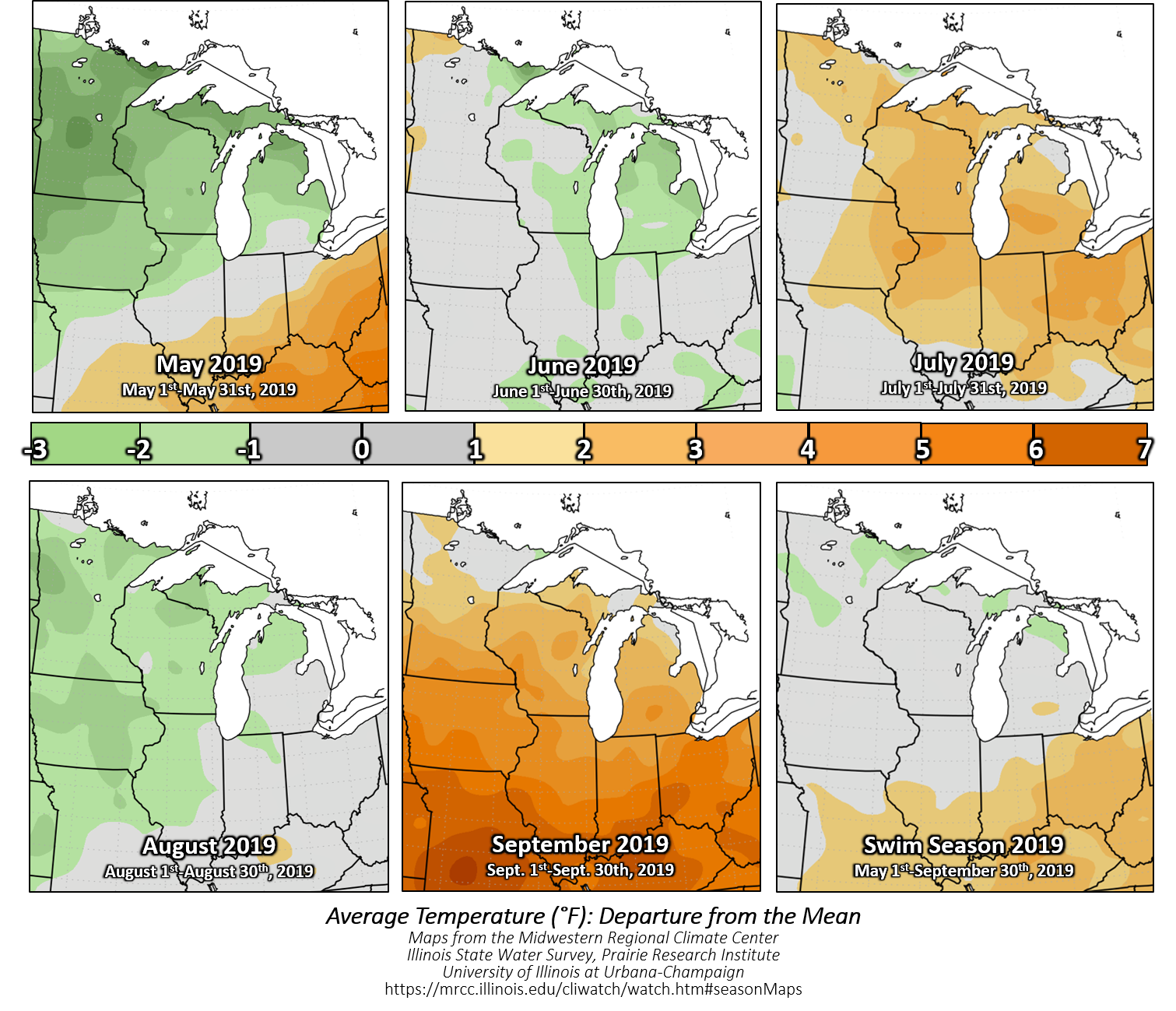

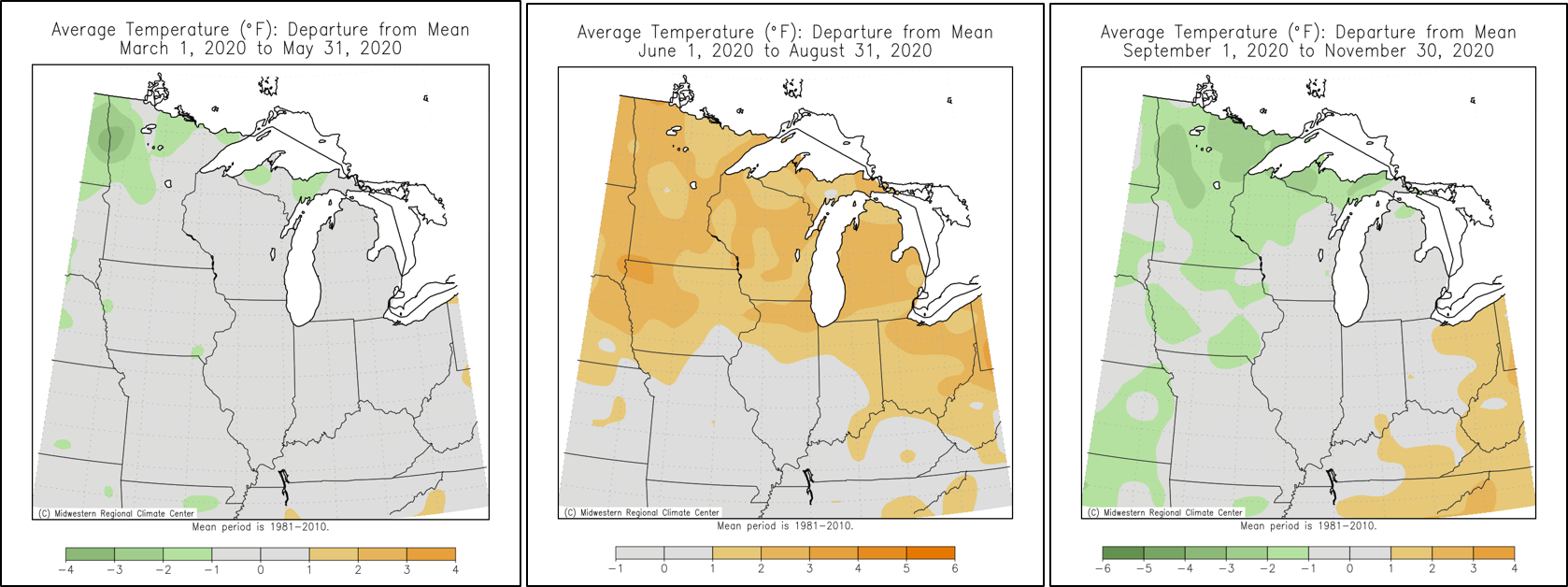

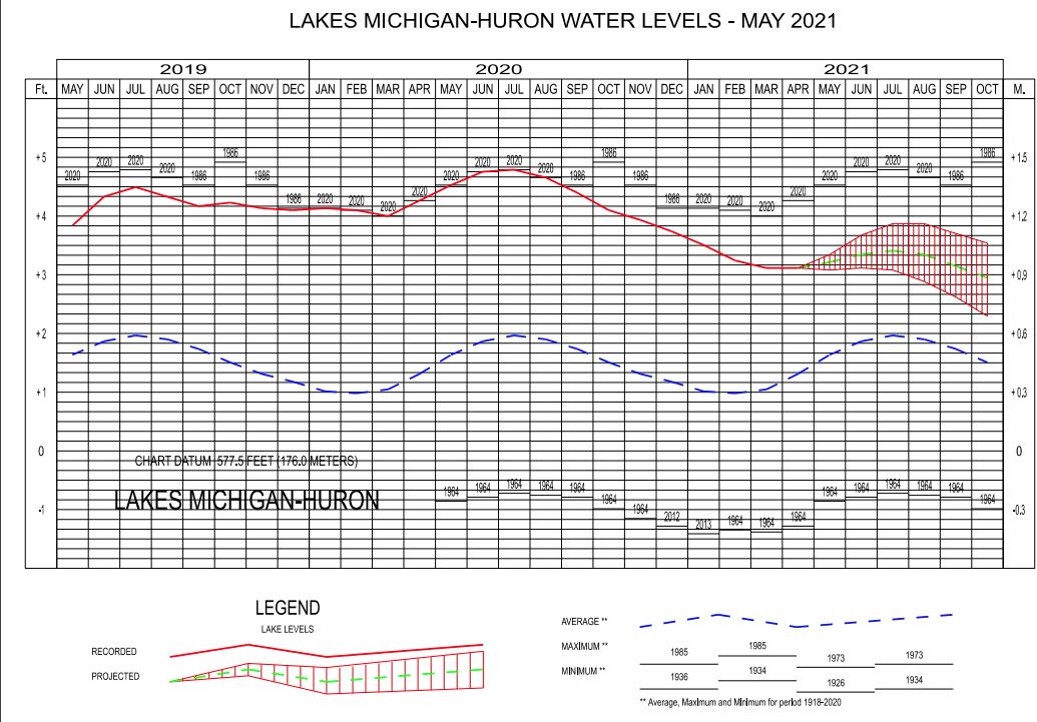

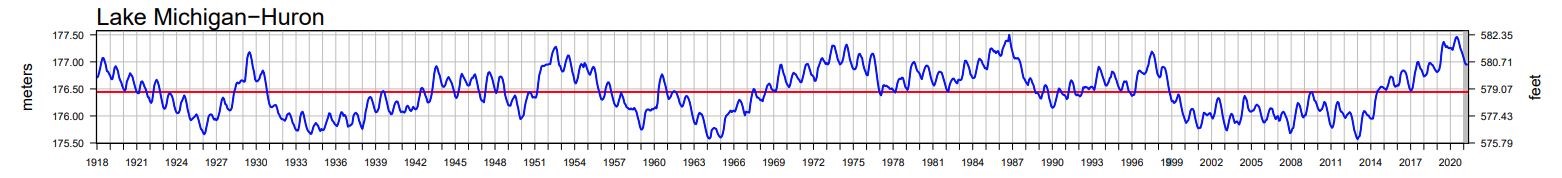

Warm water and air temperatures, along with higher water levels were likely to blame for the greater than average number of current-related incidents. Higher water levels bring the potential for increased wave energy, and increased wave energy means more beach erosion and a favorable set-up for dangerous current development (Meadows et al., 1997). You can view the latest water levels Here. There are additional links to water level information in the references at the end of this summary. Warmer water and air temperatures bring swimmers to the water. Grand Haven alone saw over 2 million visitors from just May through September (Evanoff, 2016). Air temperatures across the Great Lakes averaged between 1-5°F above the mean during the summer months (June-August). August was a particularly warm month, with temperatures 3-6°F above average for several locations around the Great Lakes (Fig. 2). It was also the month where we saw a majority of current-related incidents this season (25/44 total incidents).

Fig. 2. Midwestern Regional Climate Center (MRCC). Average temperatures (departure from the mean) for June into August 2016 (upper left), June (upper right), July (bottom left), and August (bottom right).

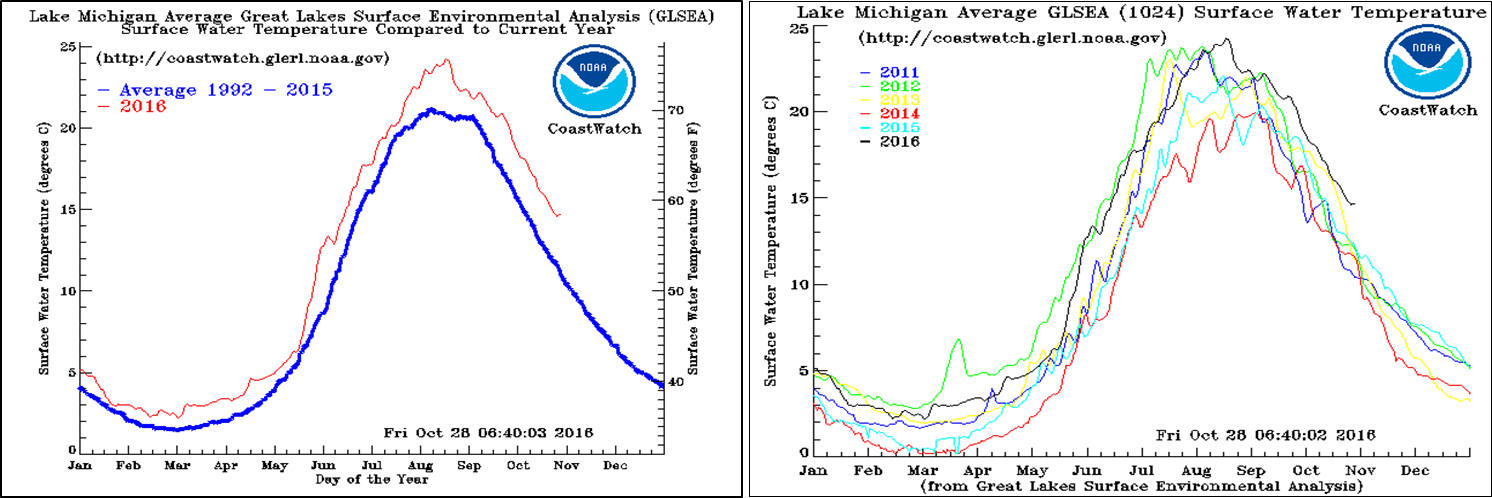

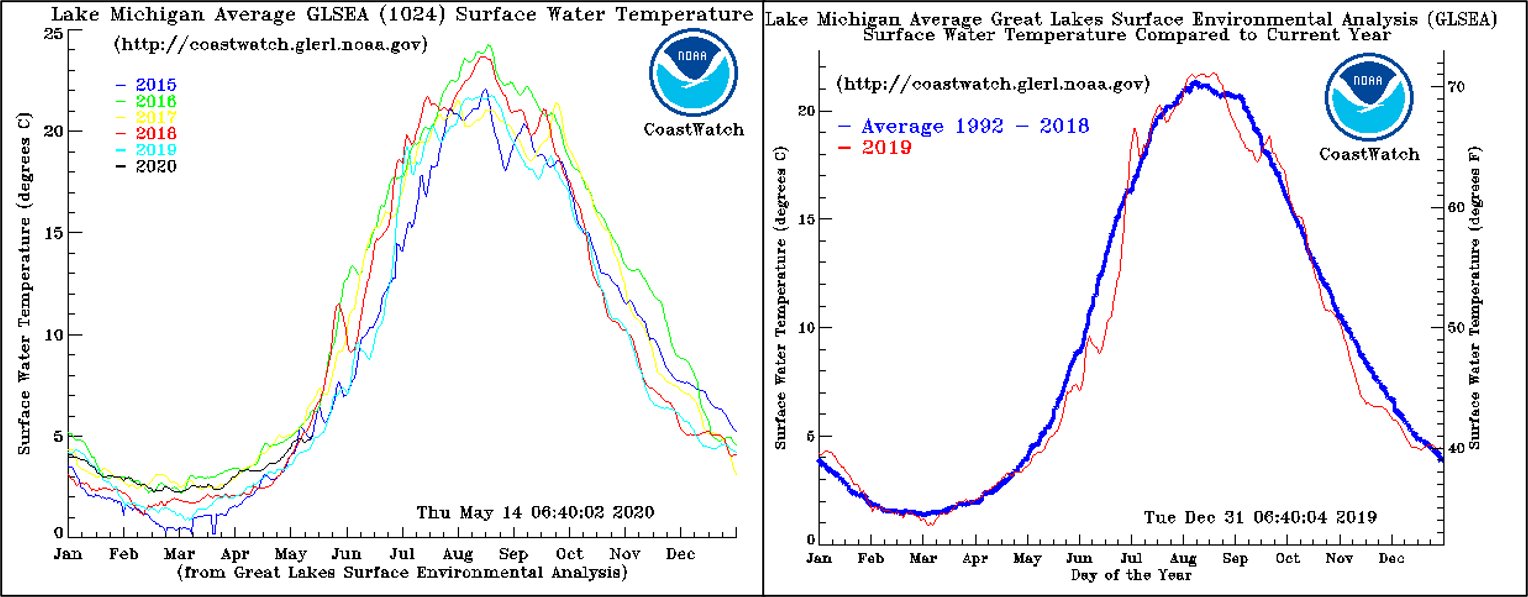

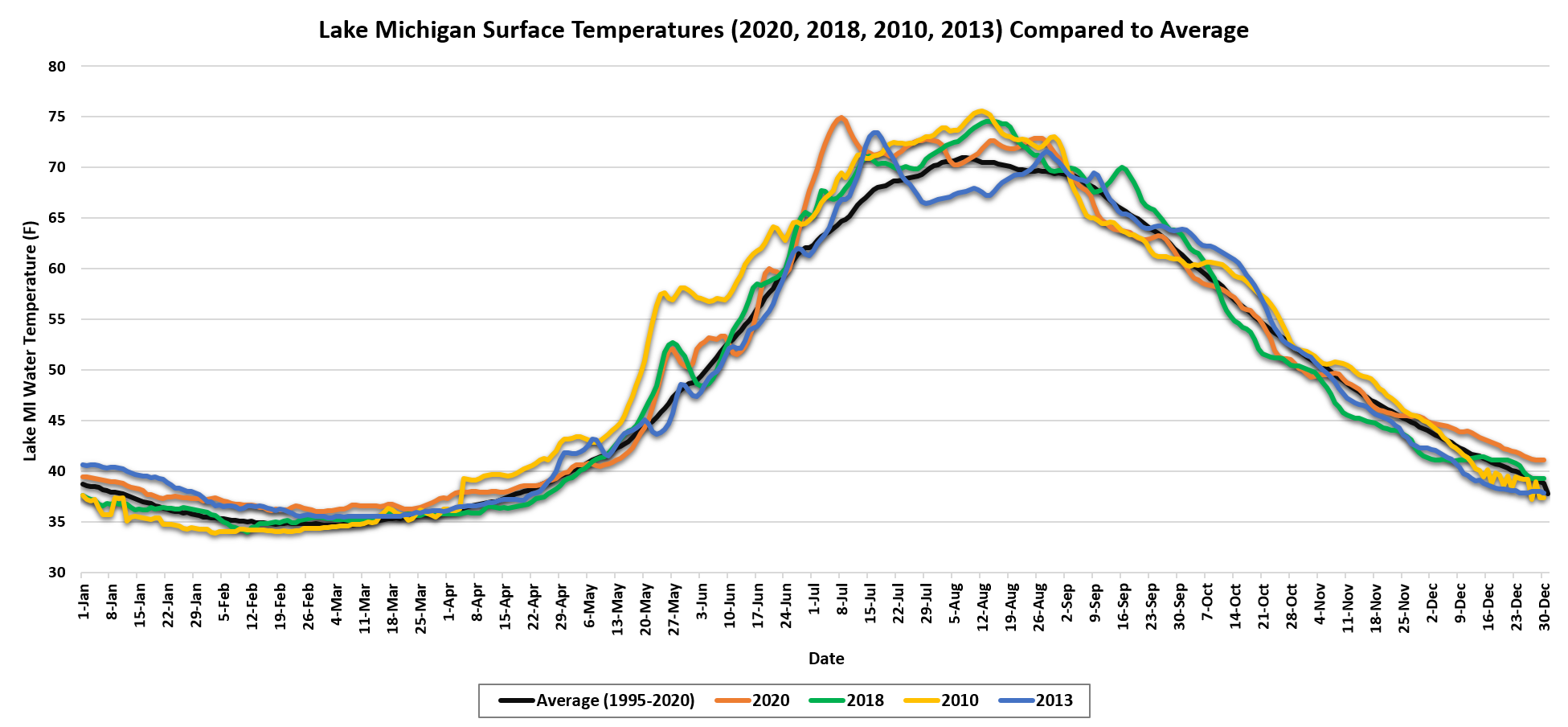

Water temperatures during the 2016 swim season were well above average, especially when compared to the past three years. Lake Michigan is shown below (Fig. 3), which is where a majority of the incidents occurred this year. 2012 was the last year where water temperatures rivaled those of this year, particularly during the month of August when we traditionally have most of our incidents. 2012 was also the last time we had an above average number of current-related incidents.

Fig. 3. Lake Michigan water temps from the Great Lakes Environmental Research Center GLSEA. Lake Michigan average water temperatures from 2016 as compared to the long term average (left) and the previous years (right).

Where Did the Incidents Occur?

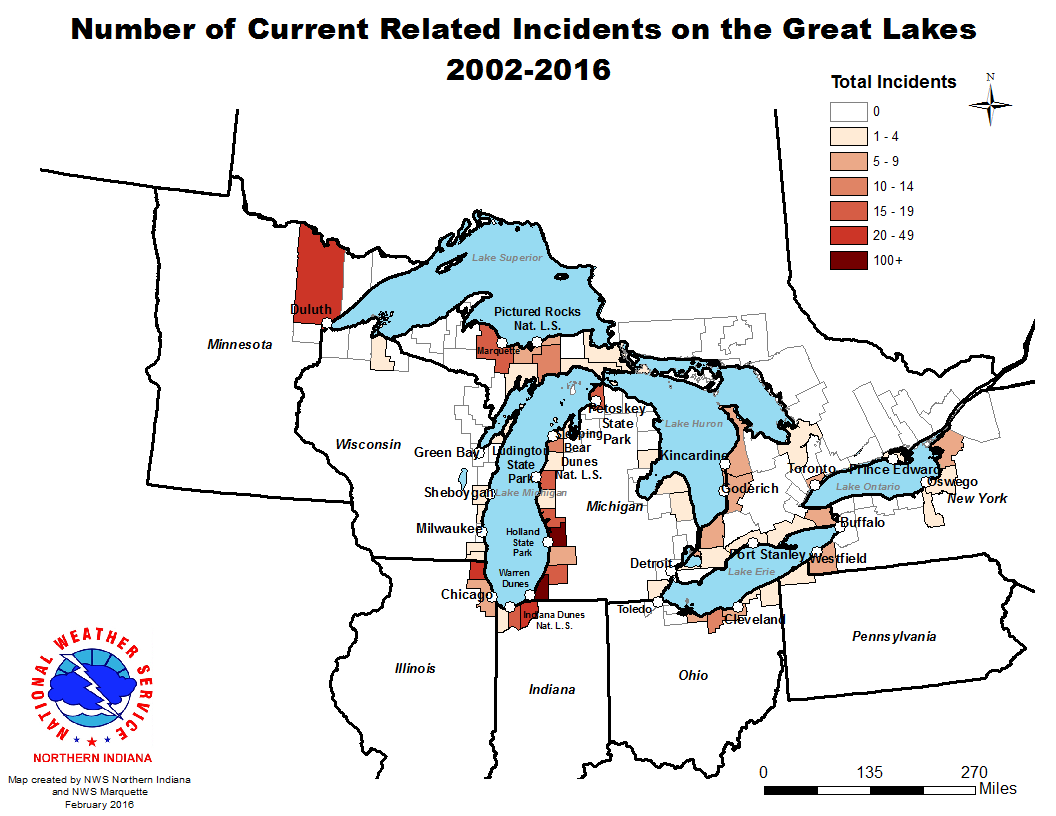

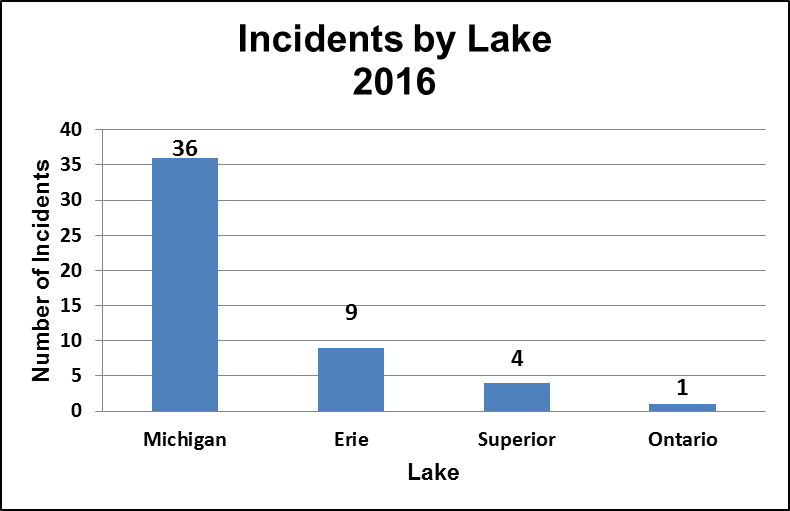

An updated map of current-related incidents from 2002-2016 is shown below (Fig. 4A). A majority of current-related incidents this year occurred on Lake Michigan (which is normal), followed by Lakes Erie, Superior, and Ontario. There were no incidents reported to us from Lake Huron (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4A. Map of Great Lakes current-related incidents (rescues and fatalities) from 2002-2016 An interactive version of this map can be found here. (GLCID, 2016).

Fig. 4b. Number of current-related incidents by Lake in 2016(GLCID, 2016).

Current Type

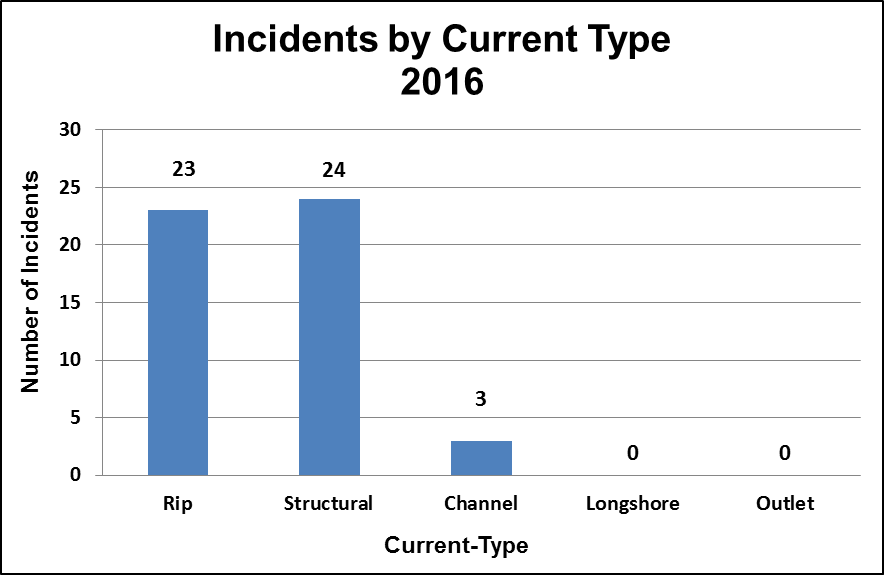

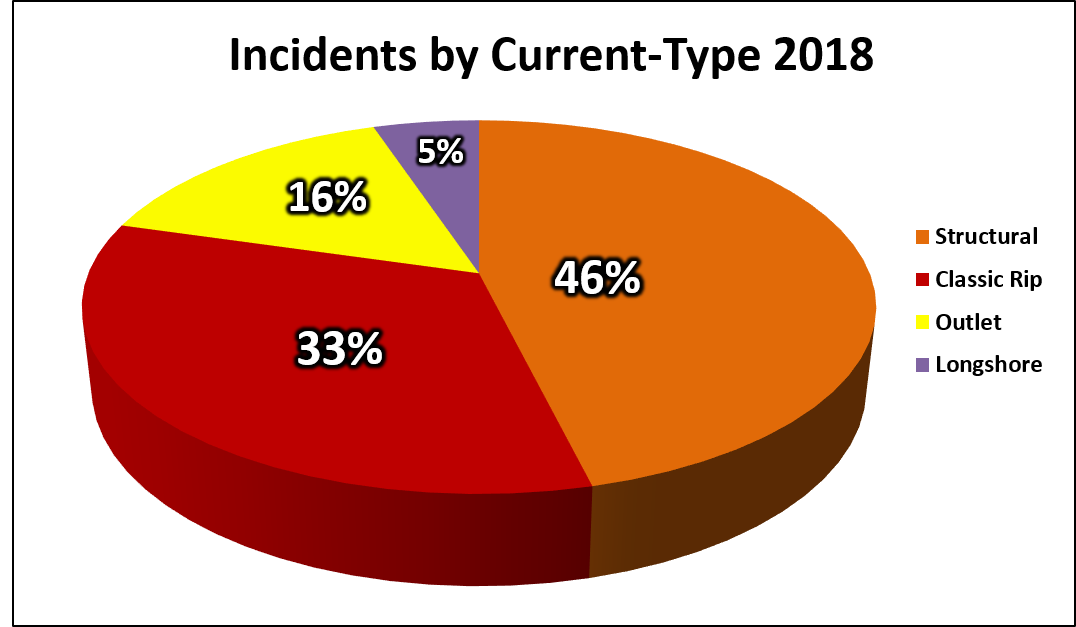

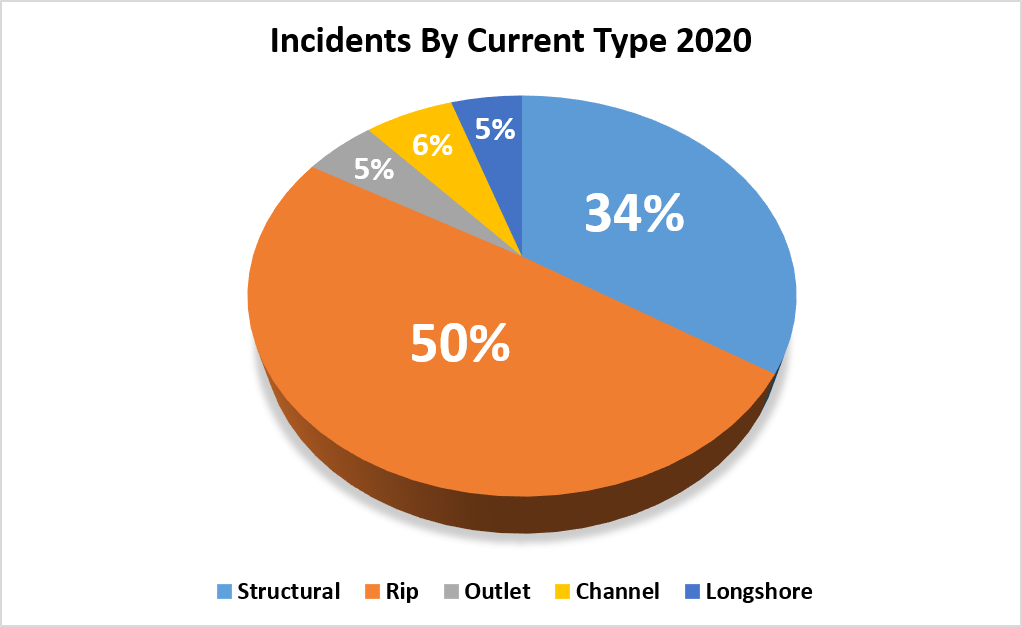

In 2016, 46% of the incidents were related to rip currents (Fig. 5), which occur within gaps in the sandbars, usually during moderate to high waves. Approximately 48% of the incidents in 2016 were related to structural currents. To see a quick reference comparing the types of dangerous currents in the Great Lakes (as depicted in Fig. 5), visit Michigan Sea Grant's dangerous currents page.

Fig. 5. Number of current-related incidents by current type in 2016(GLCID, 2016).

Conditions during Current-Related Incidents

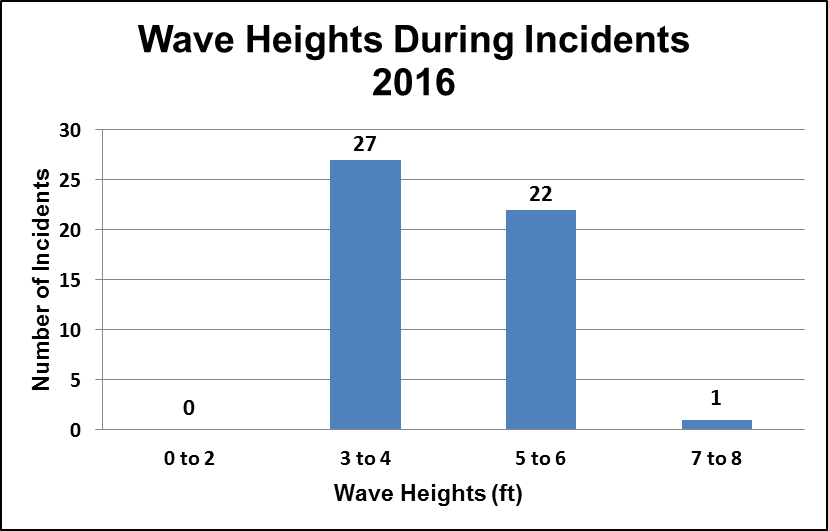

All of the 2016 incidents occurred when wave heights were 3 to 6 ft or greater (Fig. 6). This is close to the normal distribution of wave heights observed during current related incidents, with the maximum numbers of incidents usually occurring in the 3 to 4 ft range. This is when dangerous currents are likely and the bulk of swimmers are not too intimidated by the waves to enter the water. Long term trends support this, as they show the number of incidents dropping off significantly after the 5 to 6 ft range.

Fig. 6. Wave heights(ft) during current-related incidents in 2016(GLCID, 2016).

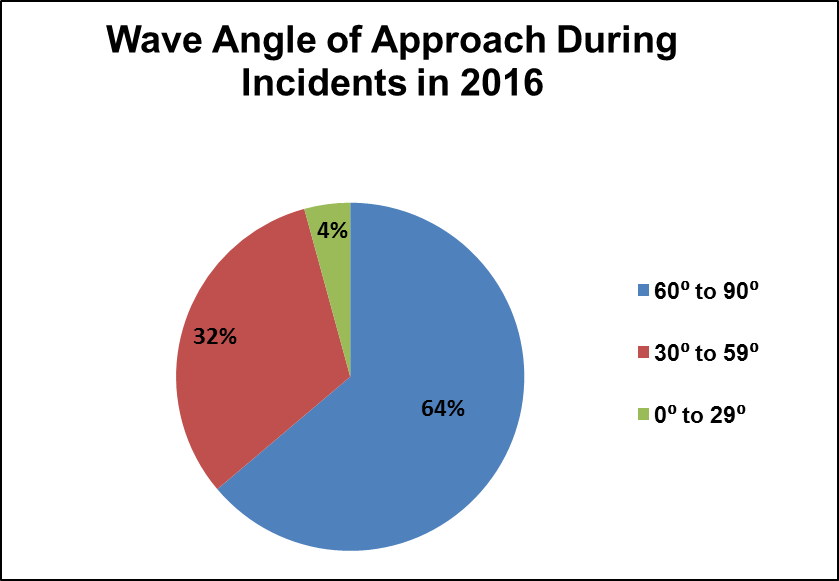

Waves approached the shore at a 60 to 90 degree angle during 64% of the incidents in 2016, and 32% of the incidents occurred when waves approached at a 30-59 degree angle relative to shore (Fig. 7). Research from both the ocean and the Great Lakes demonstrate that dangerous currents, particularly rip currents within the sandbars, are more likely as waves approach at more direct angles to the beach. This appears to be the case for 2016. The longer term incident data also suggests that a greater variety of currents may be present at these more direct angles of approach.

Fig. 7. Wave angle of approach (degrees relative to shore) during current-related incidents in 2016(GLCID, 2016).

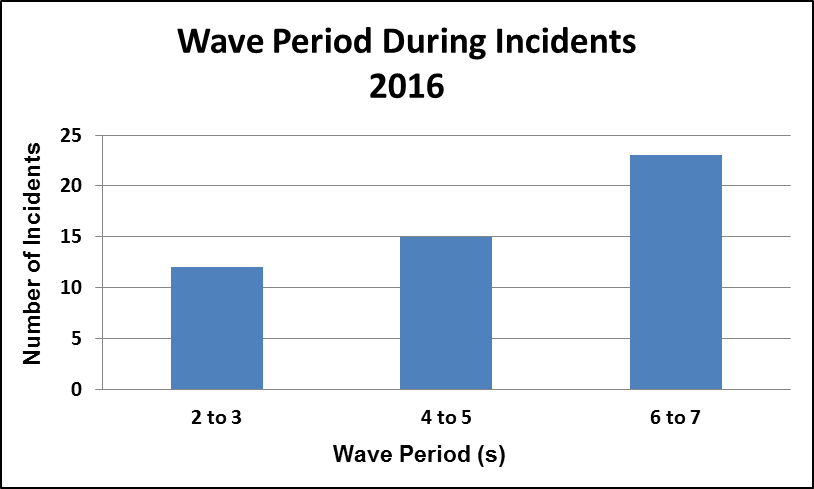

Wave periods during current related incidents in 2016 were slightly longer than what we usually see each year, on the order of 6 to 7 seconds (Fig. 8). Longer wave periods bring a larger volume of water in to shore, which leads to an increased probability of current development. The longer periods may have contributed to the greater number of classic rip current cases in 2016.

Fig. 8. Wave period(s) during current-related incidents in 2016(GLCID, 2016).

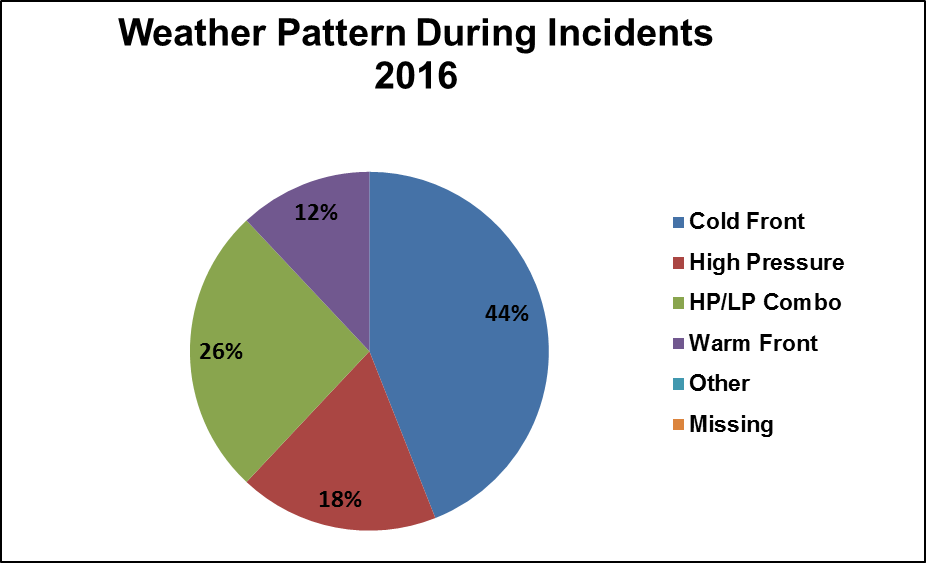

The weather pattern that brings hazardous lake conditions most often on the Great Lakes is the passage of a cold front (GLCID, 2002-2015). This was the case again in 2016, with nearly half of the incidents occurring either just prior to, during, or immediately after the passage of a cold front (Fig. 9). About 26% of the incidents occurred as a low pressure system (LP) was moving out (long after the cold front passed) and a strong high pressure system (HP) was building in, creating strong onshore winds and higher waves (HP/LP Combination).

Fig. 9. Weather pattern during current-related incidents in 2016(GLCID, 2016).

Victim Demographics

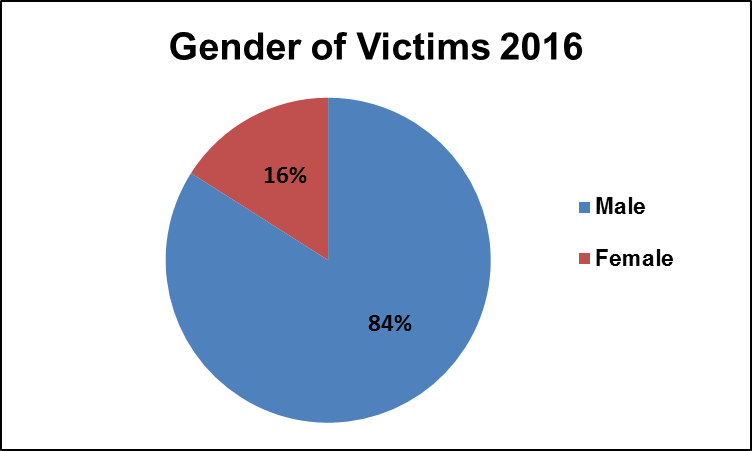

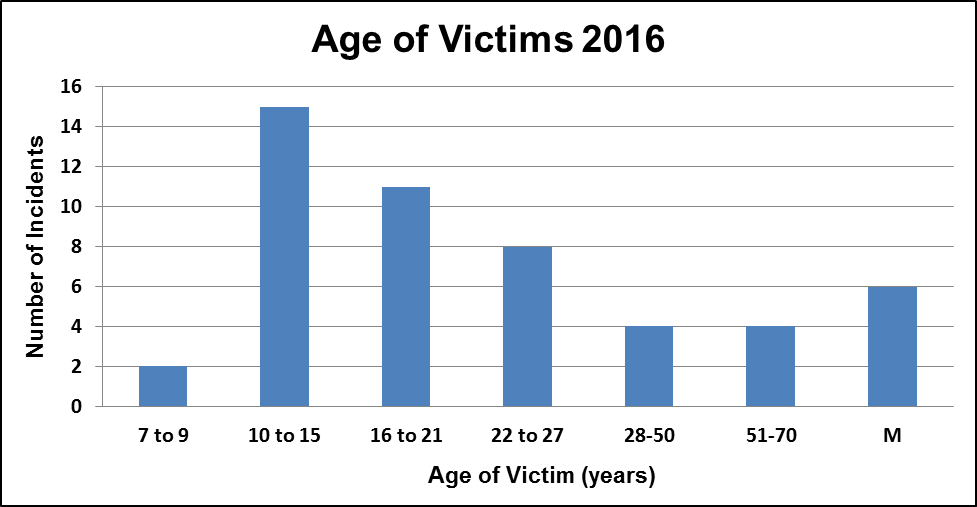

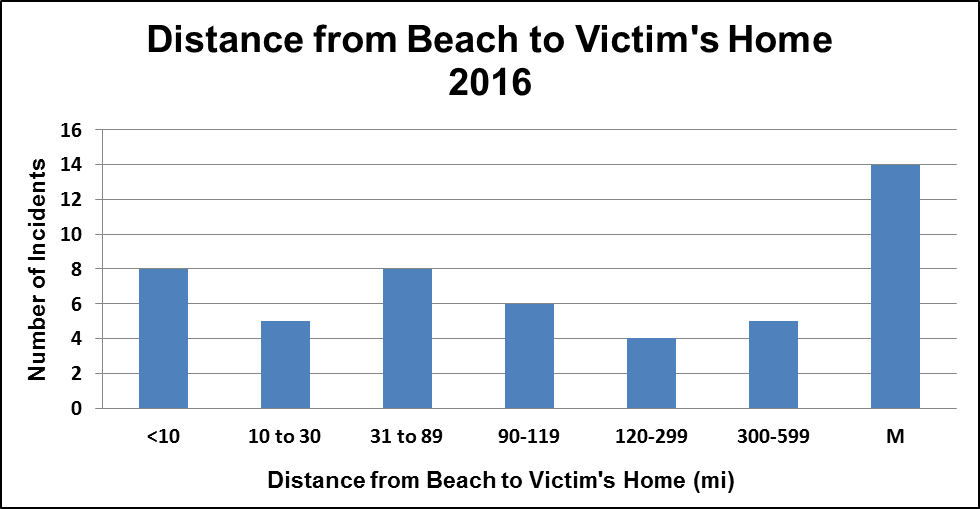

GLCID data from 2002-2015 shows that a majority of victims involved in current-related incidents are adolescent- young adult aged males who live within 90 miles of the beach where the incident occurred. This year, 84% of the victims were male (Fig. 10) and between the ages of 10 and 27 (Fig. 11). The only difference between 2016 and the long term data was that there was more of an even distribution in the distance from the beach to the victim's hometown (Fig. 12). Note that there was a large portion of this data missing (a total of 14 incidents).

Fig. 10. Gender of victims involved in current-related incidents 2016(GLCID, 2016).

Fig. 11. Age of victims involved in current-related incidents 2016(GLCID, 2016).

Fig. 12. Distance from beach where the incident occurred to the victim's hometown(GLCID, 2016).

Summary and Closing Thoughts

In summary, current related rescues and fatalities were slightly above average for the 2016 swim season, with 16 fatalities and 34 rescues (two still in critical condition as of 12/22/2017). Warm water and air temperatures, along with higher water levels were likely to blame for the greater than average number of current-related incidents in 2016. While numbers are slightly above average, it is important to recognize that the number of incidents has still decreased since the 2010-2012 time-frame, where air and water temperatures were comparable to this year (versus 2013-2015). I believe this is due to improvements in beach safety measures across the Great Lakes.

For beachgoers, note that the data is clear. To be safe on the Great Lakes, stay dry when waves are high and steer clear of the pier. Before you leave the beach, check the National Weather Service beach forecasts and watch for beach hazards statements, both of which will tell you when conditions are going to be inappropriate for swimming. This forecast is produced at least twice daily during the swim season each year (roughly Memorial Day to Labor Day).

To see a review of all the Great Lakes Current Incident Database statistics, click “about” at the top of this page. You will also find a summary of how the data is collected, where you can submit corrections or information about current-related incidents, and even search the database. For questions/comments/concerns, please contact megan.dodson@noaa.gov

References and Resources

Great Lakes Current Incident Database (GLCID, National Weather Service, 2017). https://www.weather.gov/iwx/beach_season_summaries

Great Lakes Environmental Research Center (GLERL/GLSEA, 2017): https://coastwatch.glerl.noaa.gov/statistic/

Great Lakes Surf Rescue Project: https://www.glsrp.org

Great Lakes Water Safety Consortium (2017): Get involved: https://greatlakeswatersafety.org/

Meadows, G.A., Meadows, L.A., Wood, W.L., Hubertz, J.M., & Perlin, M. (1997): Journral Ametsoc.

Midwestern Regional Climate Center (MRCC, 2016):https://mrcc.isws.illinois.edu/cliwatch/watch.htm#

Michigan Sea Grant (2016):https://www.dangerouscurrents.org

Evanoff, M. (2016). Michigan State Park Attendance: June-September 2016. Personal correspondence.

NWS Beach Forecast Page: https://www.weather.gov/greatlakes/beachhazards

Additional research on dangerous currents:https://www.weather.gov/iwx/beachpage_references

Great Lakes Water Levels Info

Overview

Current related fatalities were well below average for the 2017 swim season, with only 7 occurring through January 1, 2018. On the other hand, rescues were slightly above the average at 26. The ten-year average from the Great Lakes Current Incident Database (GLCID) is 12 fatalities and 23 rescues per year (2002-2011). It was an atypical year, with weather patterns favoring more easterly flow than what we normally see. This led to most of the current related incidents being on the western sides of the Great Lakes. Colder than average temperatures in mid-late August and increased water safety measures could have led to the lower than average number of drowning fatalities.

Fig. 1.Number of current-related incidents by year (2002-2017). 2017 had less current-related fatalities than average, and slightly more rescues than average (GLCID, 2017).

Air & Water Temperatures

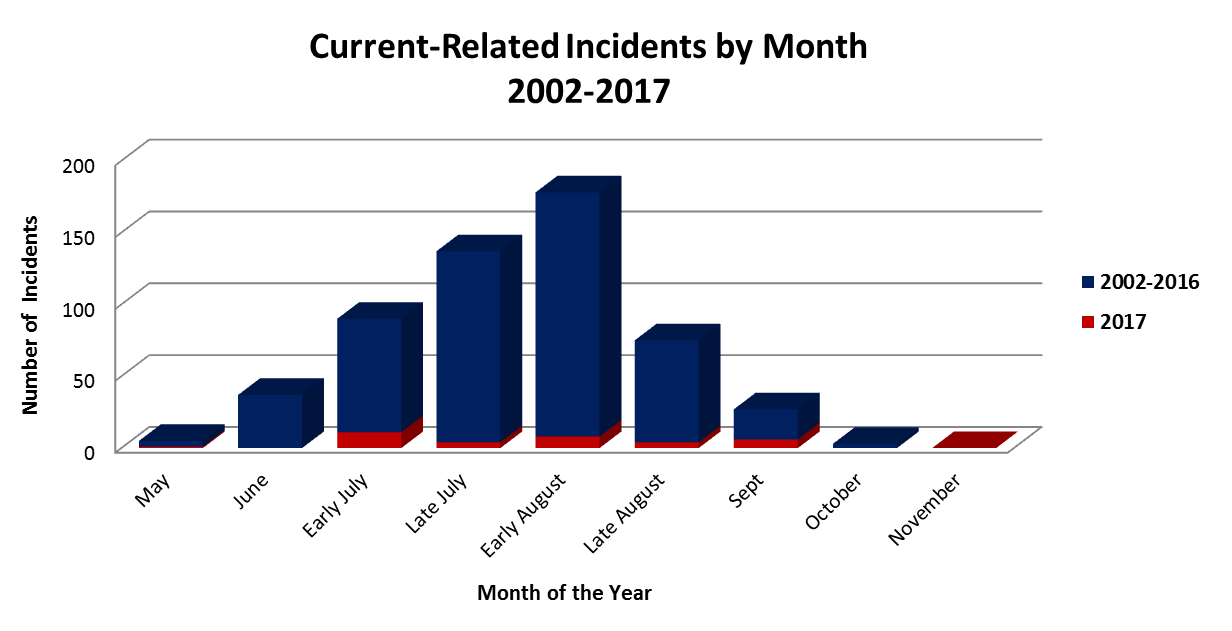

Normally, we see a majority of current-related incidents in the month of August. This year, however, we saw fewer incidents than average during late August (defined as Aug 15-31st), possibly due to colder air temperatures at that time (Fig 2a). Most of our rescues and fatalities occurred in early July (defined as July 1st-July 15th). There were no current-related fatalities or rescues reported in October and November, which is pretty typical.

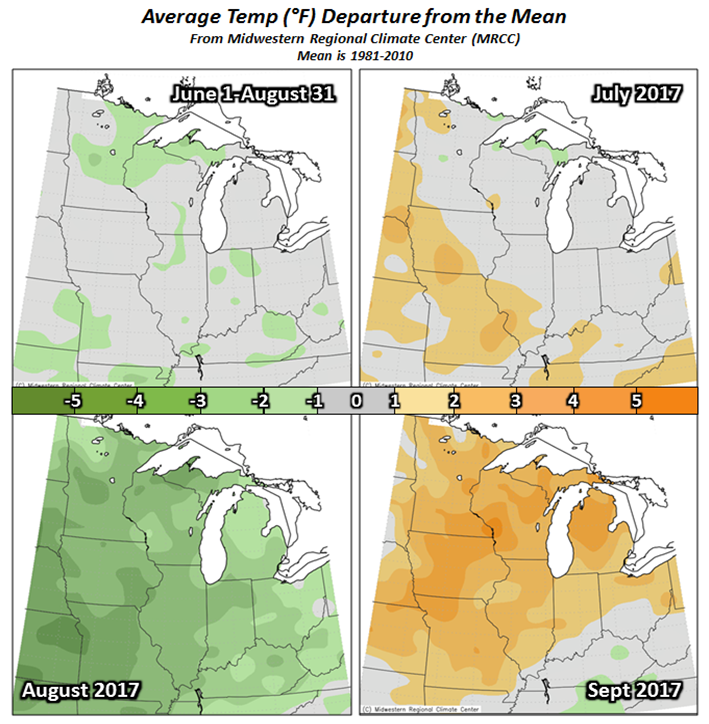

Fig. 2a. Midwestern Regional Climate Center (MRCC). Average temperatures (departure from the mean) for June 1 through August 31, 2017 (upper left), July(upper right), August (bottom left), and September (bottom right).

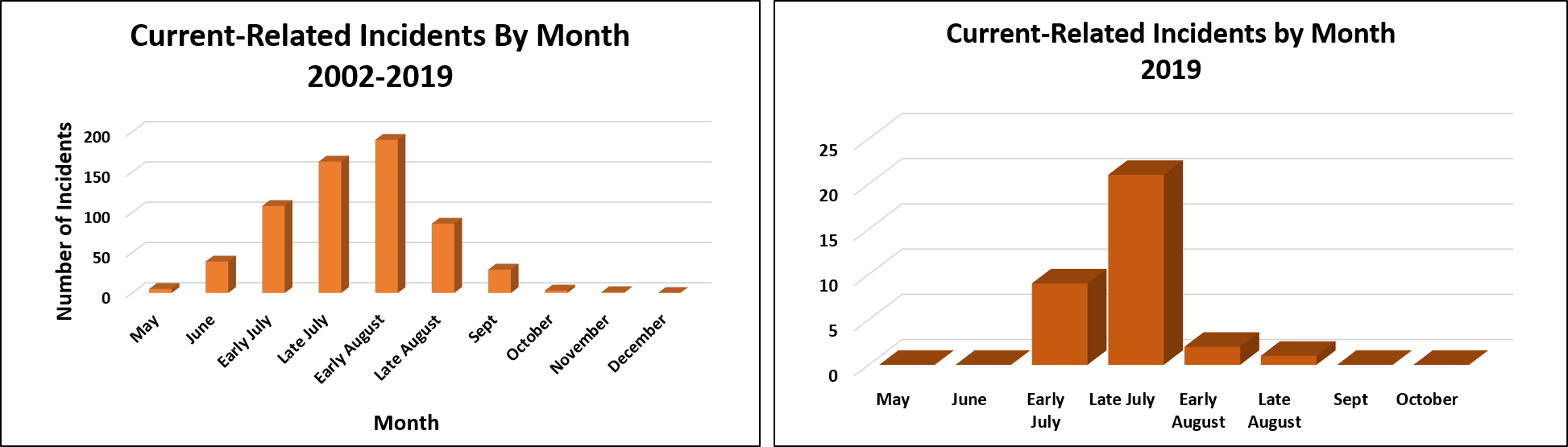

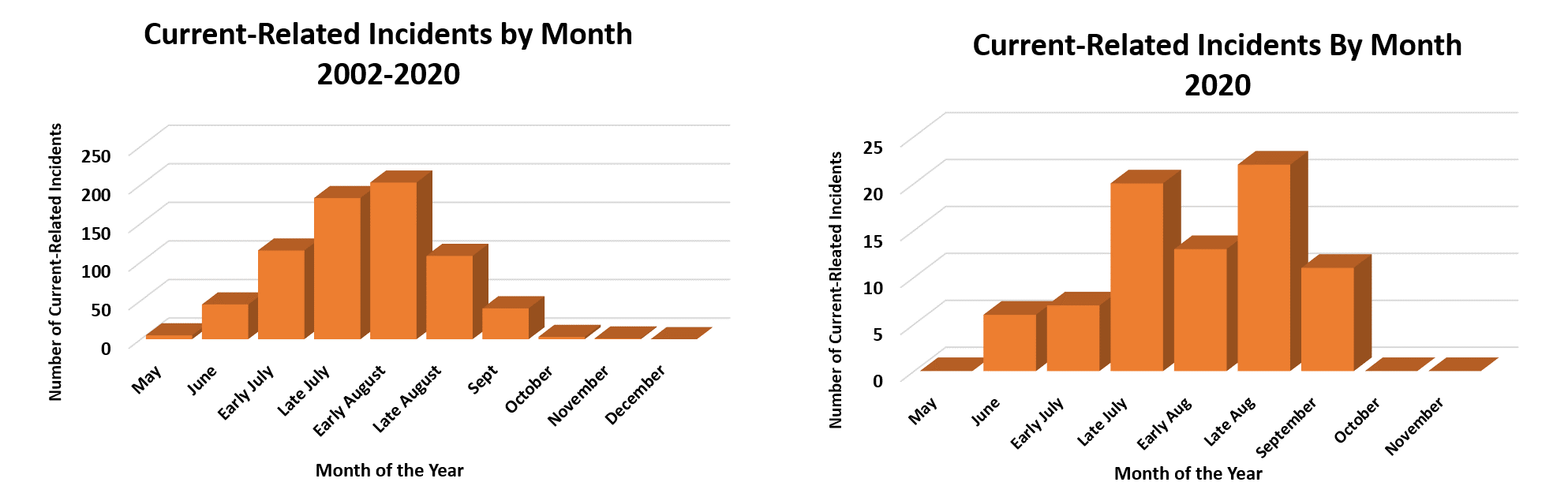

Fig. 2b. Current-related incidents by month, comparing 2002-2016 to 2017 (GLCID, 2017).

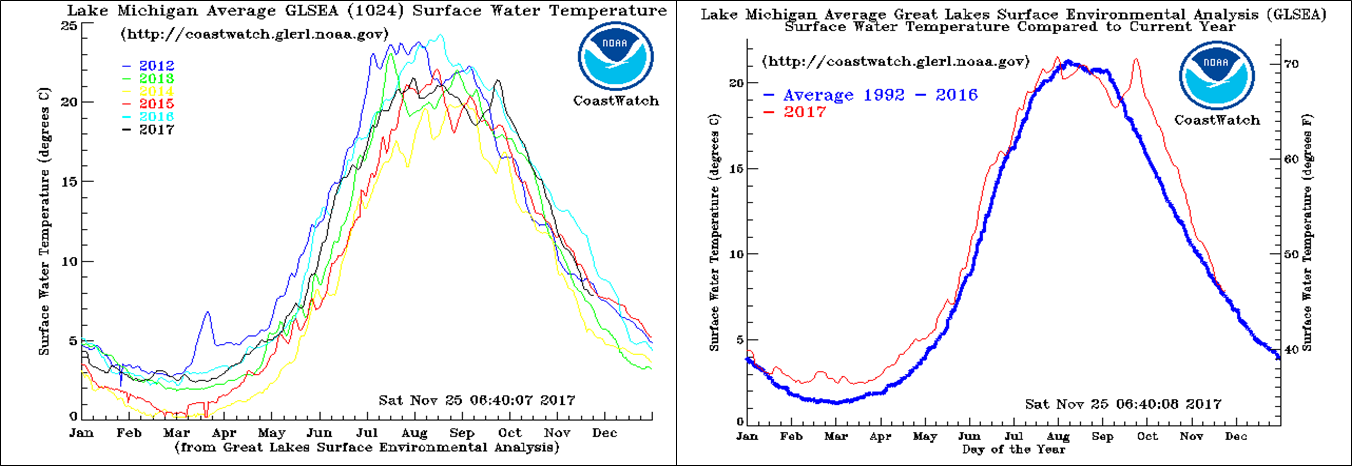

Water temperatures during the 2017 swim season were slightly above average (Fig. 3), with the exception of an unusual high spike in September-October. Lake Michigan water temperatures are shown below, which is where a majority of the incidents occurred this year (Fig. 5). It is surprising that despite the warmer water temperatures we still had a lower number of current-related fatalities.

Fig. 3. Lake Michigan water temps from the Great Lakes Environmental Research Center GLSEA. Lake Michigan average water temperatures from 2017 as compared to the long term average (right) and the previous years (left).

Where Did the Incidents Occur?

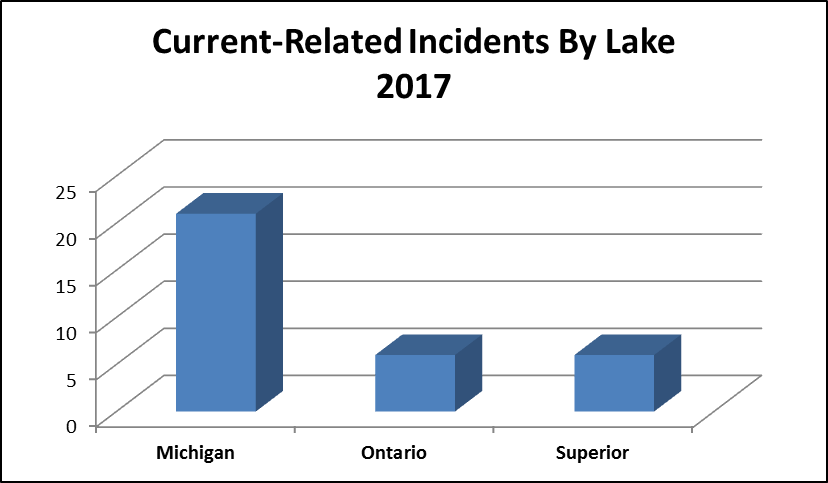

An updated map of current-related incidents from 2002-2017 is shown below (Fig. 4). A majority of current-related incidents this year occurred on Lake Michigan (which is normal), followed by Lakes Ontario and Superior. There were no incidents reported to us from Lake Huron or Lake Erie (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4. Map of Great Lakes current-related incidents (rescues and fatalities) from 2002-2017 An interactive version of this map can be found here. (GLCID, 2017).

Fig. 5. Number of current-related incidents by Lake in 2017(GLCID, 2017).

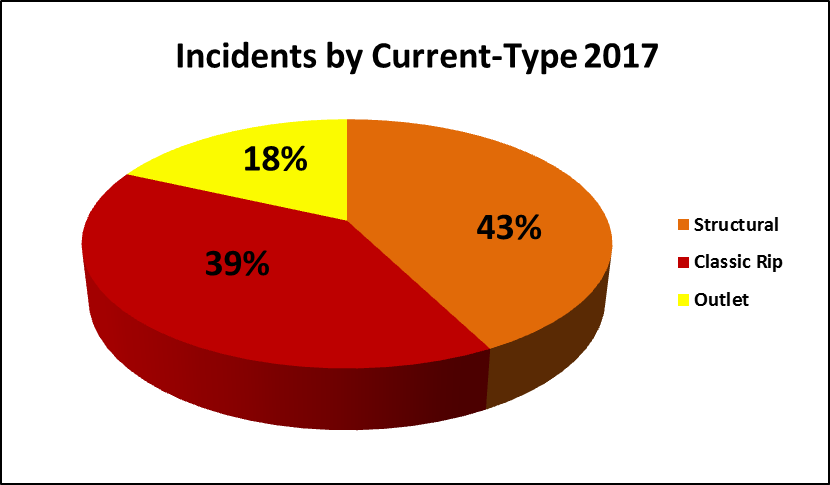

In 2017, we saw nearly equal numbers of structural and classic rip current related incidents. In the early years of data collection (2002-2012), the majority of current-related incidents (roughly 60%) occurred near shoreline structures. This was likely due to several rare events where over 18 people were rescued from strong structural currents and waves in the same location on the same day (see fig. 1). I suspect in reality we probably see a more equal distribution of both current-types developing under similar conditions, though we can only speculate based on what we know about current development.

Fig. 6. Incidents by Current-Type in 2017(GLCID, 2017).

Conditions at the Time of Incidents

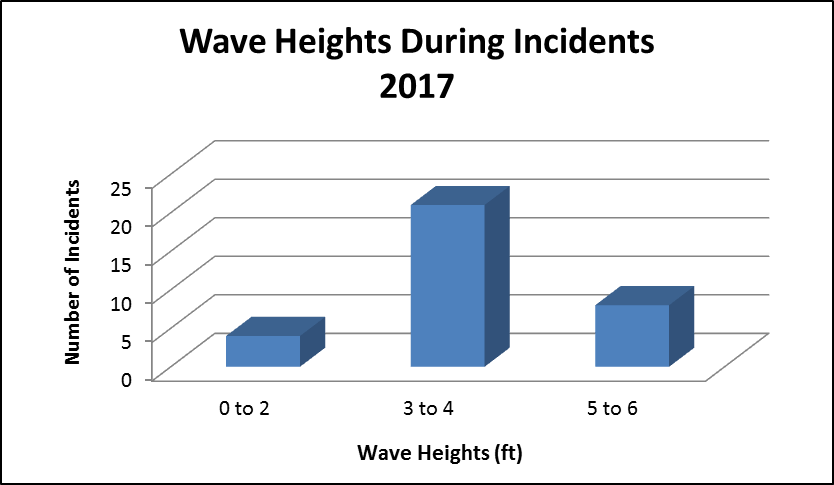

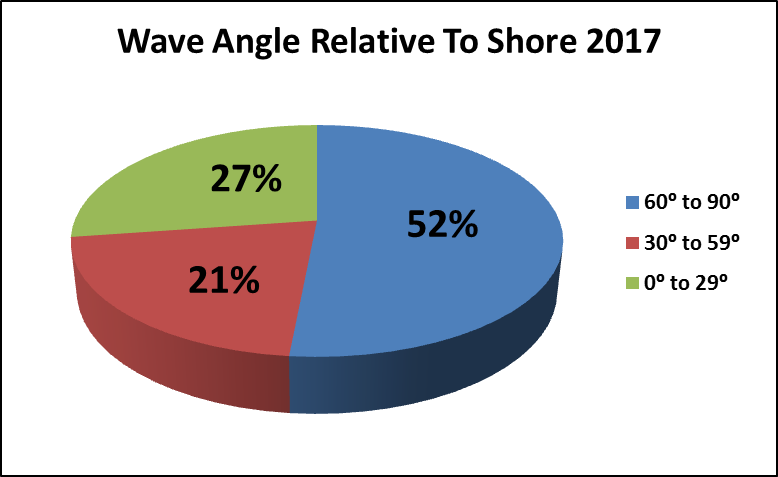

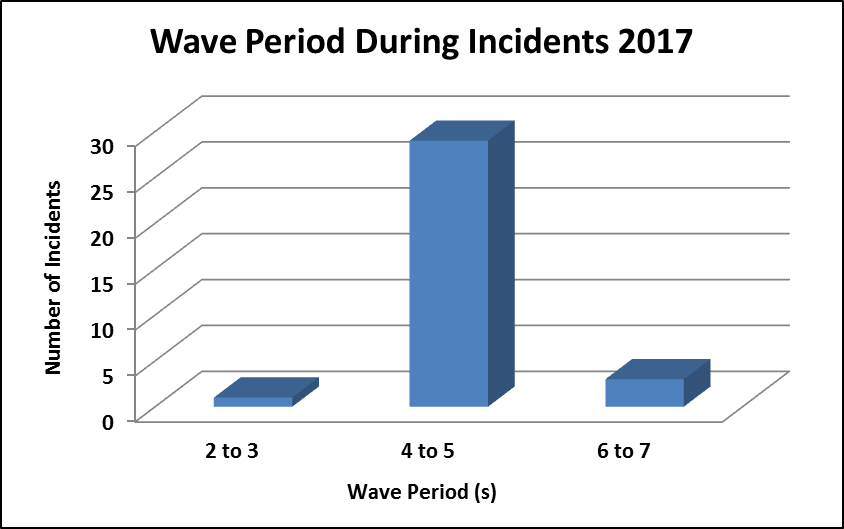

Conditions during the incidents were what would be expected given the 2002-2016 data. A majority of the incidents occurred with waves of 3 feet or greater (Fig. 7) approaching the shoreline at a 60-90 degree angle (Fig. 8), with periods of 4 to 5 seconds (Fig. 9).

Fig. 7. Wave heights during incidents in 2017 (GLCID, 2017).

Fig. 8. Wave angle of approach relative to shore during incidents in 2017 (GLCID, 2017).

Fig. 9. Wave periods during incidents in 2017 (GLCID, 2017).

If you split up the incidents by current type for 2017, classic rip currents occurred with longer wave periods, more direct approaches, and generally higher wave heights than structural currents. All four incidents that occurred during wave heights of two feet or less were near shoreline structures, like piers and breakwalls.

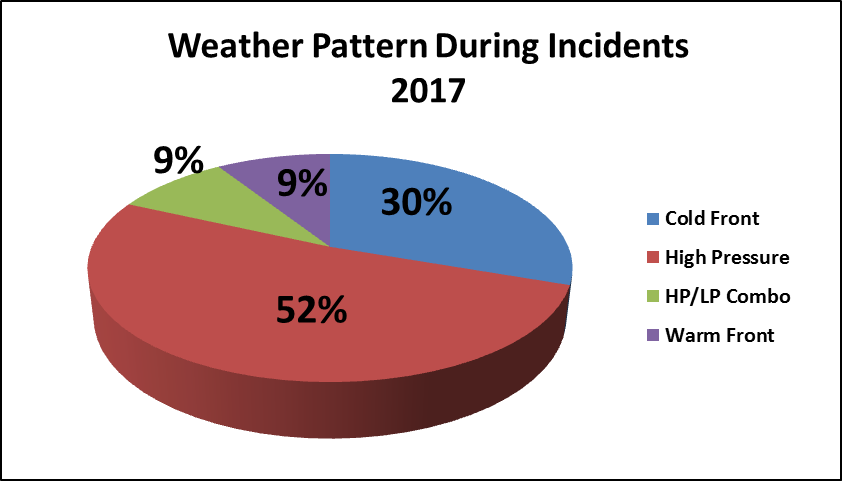

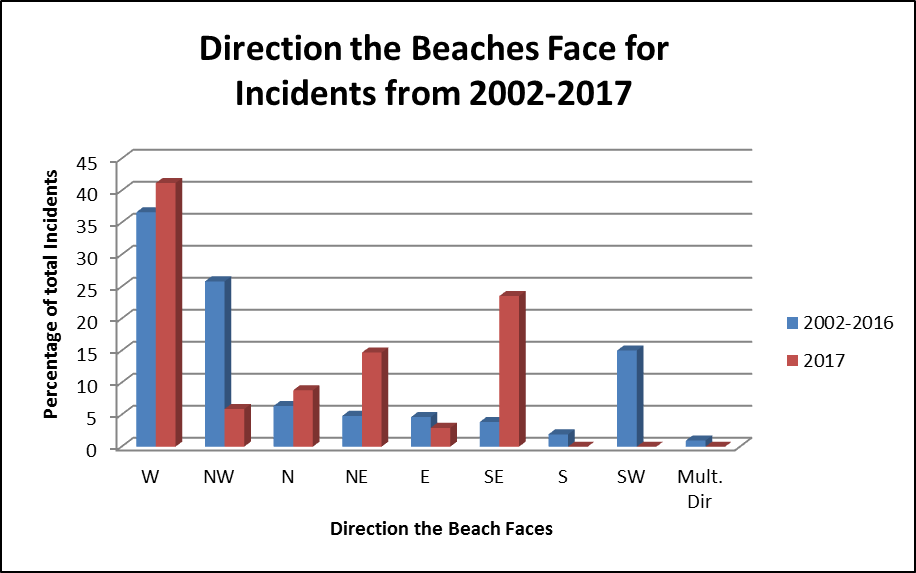

The weather pattern during incidents was atypical this year. Usually we see a majority of incidents (around 60%) occur around the time when a cold front is crossing the lake where the incident occurred. This year, we saw a larger percentage of incidents occur when there was a high pressure system creating stronger onshore flow or even a warm front creating more direct onshore approaches on the western side of Lake Michigan (Figure 10a). When you compare the beaches where incidents occur from 2002-2017 (Fig 10b), you can see a large portion of the incidents occurred at westward facing beaches. This is expected given the prevailing winds in the US are the westerlies. This was similar to this year, where nearly half of the incidents were at westward facing beaches. The unusual aspect of 2017 was the higher percentage of beaches facing a NE or SE direction. While 2002-2016 data demonstrated that SE facing beaches saw only 4% of incidents, the 2017 data had nearly a quarter of the incidents at SE facing beaches.

Fig. 10a. Weather pattern during current related incidents in 2017 (GLCID, 2017).

Fig. 10b. Percentage of incidents that occur at various beach-facing directions. For example, roughly 37% of incidents from 2002-2016 occurred at westward facing beaches (GLCID, 2017).

Victim Demographics

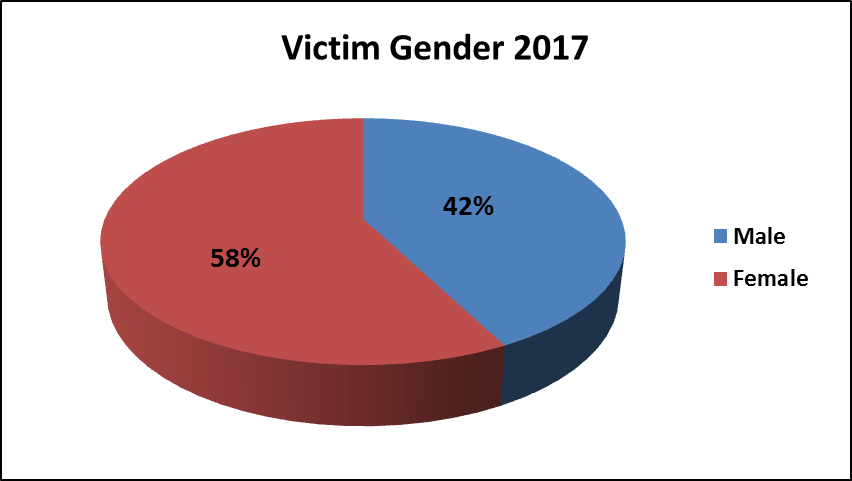

Another interesting aspect of 2017 was that we saw that more females than males were involved in current-related incidents (Fig. 11). In the 2002-2016 data, around 80% of victims are male.

Fig. 11. Gender of victims involved in current-related incidents in 2017 (GLCID, 2017).

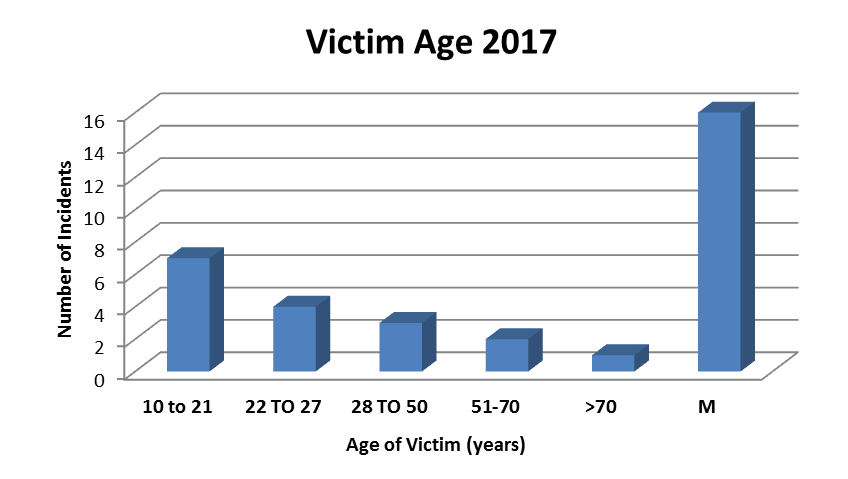

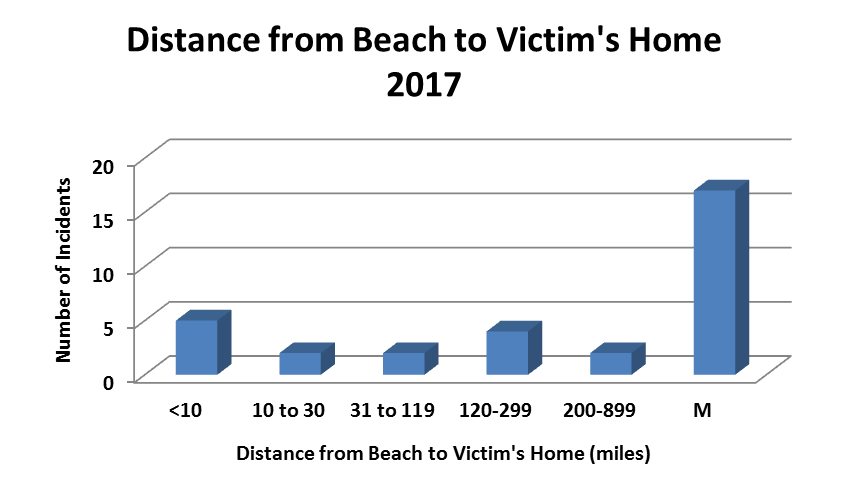

Unfortunately, I was unable to narrow down the details such as age and hometown for many of the rescue victims. I am still working with authorities to obtain the information as of March 7, 2018 and will update the graphs and this webpage as soon as I hear back from these agencies. However, the data I was able to collect regarding the age (Fig. 12) and distance from the beach to victim's hometowns (Fig. 13) is fairly typical of what we see annually. Victims were younger, mainly between the ages of 10 and 21. It was roughly half and half between victims who lived within 30 miles of the beach where the incident occurred, and those who were tourists (Defined as anyone who lives further than 30 miles from the beach).

Fig. 12. Age of victims involved in current-related incidents in 2017 (GLCID, 2017).

Fig. 13. Distance from beach where the incident occurred to the victim's hometown in 2017(GLCID, 2017).

Summary

In summary, 2017 was a below average year in terms of current-related fatalities. We can only speculate as to the reasons, but I suspect it relates to a colder than average August. Additionally, we know that at least four of the incidents were rescues due to water safety efforts, where recently installed lifesaving equipment was used for a quick rescue. Had we had four drownings that day instead of rescues, this year would have been closer to average. One final note is that as of 12/22/17 I am still working to confirm or rule out currents as being a partial cause of one fatality. Unfortunately, due to difficulties reaching those who were eyewitnesses or involved in rescue/recovery operations, it may be some time before these are added to the database. If these are confirmed, it will bring the totals to 8 fatalities and 27 rescues. Should this occur, I will update the webpage graphs. It is also important to notice that the 2016 swim season summary was updated to include additional fatalities and rescues that were sent to us over the winter of 2016-2017. The graphs on our overview page were also updated to account for the 2016 and 2017 swim season updates. If you know of a current-related rescue or drowning that is not included in the 2002-2017 data, please fill out this form. This will send megan.dodson@noaa.gov a direct email with the information needed to add it to the database. Thank you to those who provided data for the Great Lakes Current Incident Database during the 2017 swim season. The data helps us to get a handle on the weather and water conditions present during incidents, and hopefully fulfill our mission of protecting lives (and ending drowning on the Great Lakes).

References and Resources

Great Lakes Current Incident Database (GLCID, National Weather Service, 2017). https://www.weather.gov/iwx/beach_season_summaries

Great Lakes Environmental Research Center (GLERL/GLSEA, 2017): https://coastwatch.glerl.noaa.gov/statistic/

Great Lakes Surf Rescue Project: https://www.glsrp.org

Great Lakes Water Safety Consortium (2017): Get involved: https://greatlakeswatersafety.org/

Meadows, G.A., Meadows, L.A., Wood, W.L., Hubertz, J.M., & Perlin, M. (1997): Journral Ametsoc.

Midwestern Regional Climate Center (MRCC, 2016):https://mrcc.isws.illinois.edu/cliwatch/watch.htm#

Michigan Sea Grant (2016):https://www.dangerouscurrents.org

Evanoff, M. (2016). Michigan State Park Attendance: June-September 2016. Personal correspondence.

NWS Beach Forecast Page: https://www.weather.gov/greatlakes/beachhazards

Additional research on dangerous currents:https://www.weather.gov/iwx/beachpage_references

Great Lakes Water Levels Info

https://www.glerl.noaa.gov/data/dashboard/GLWLD.html

https://www.glerl.noaa.gov/data/wlevels/#overview

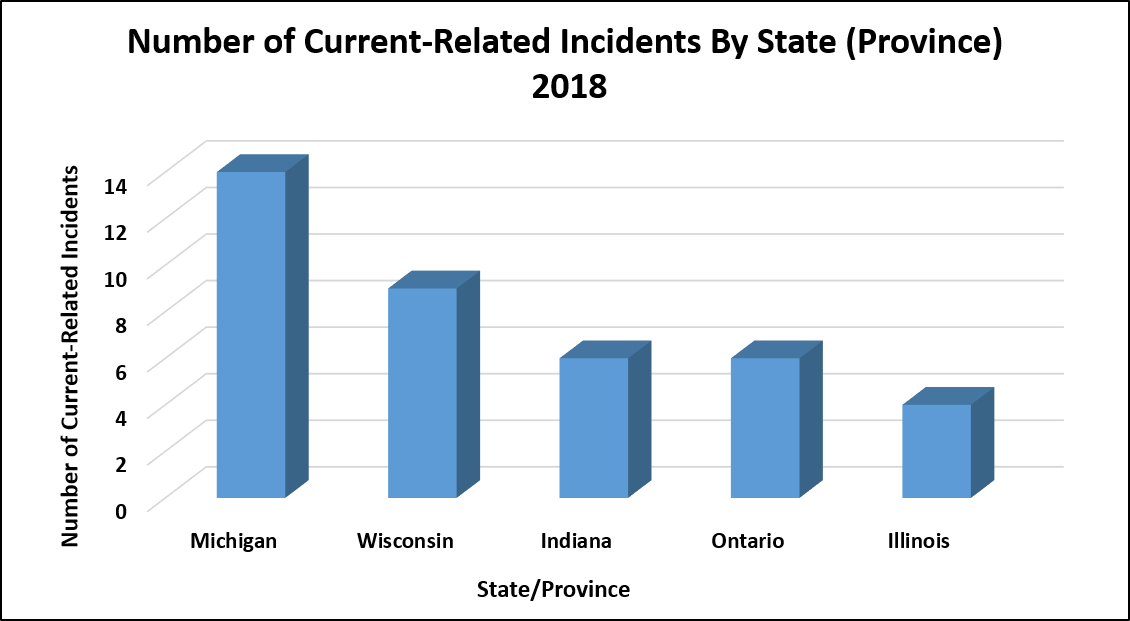

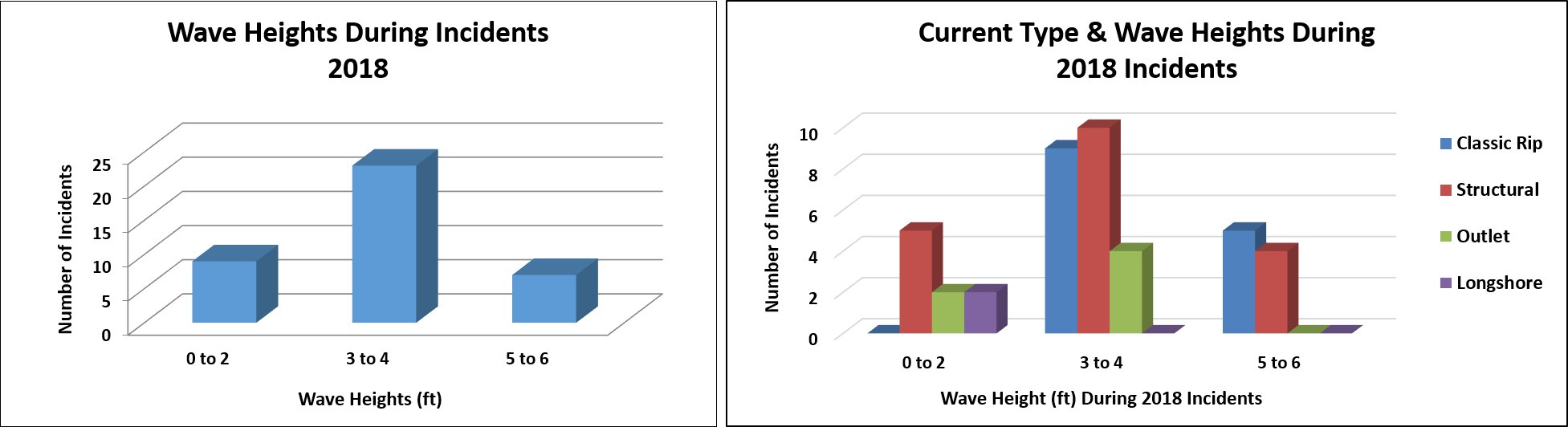

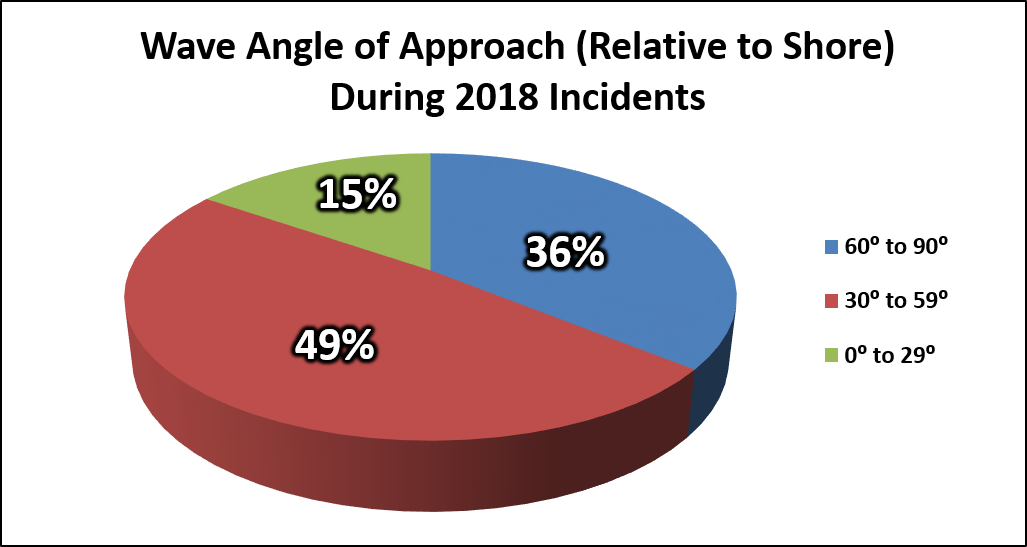

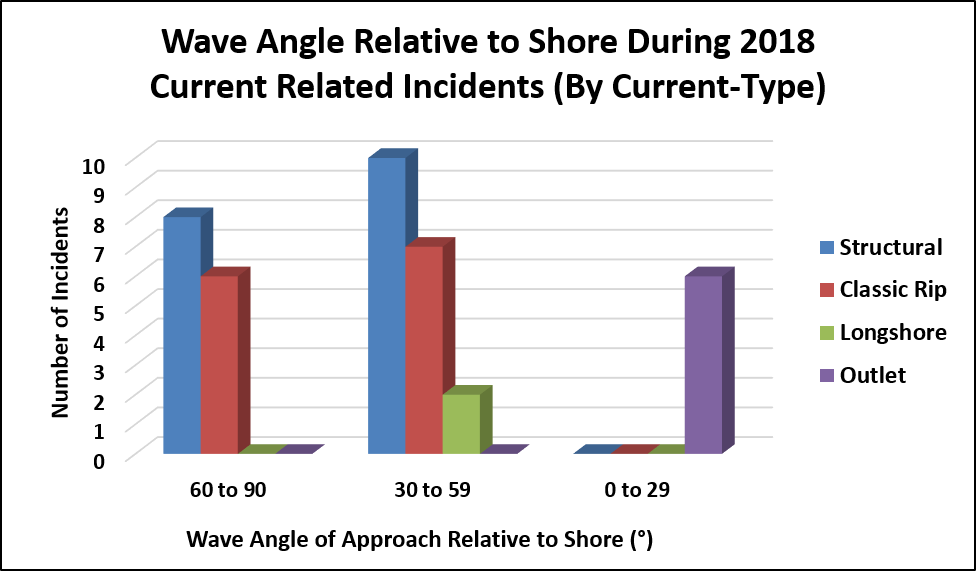

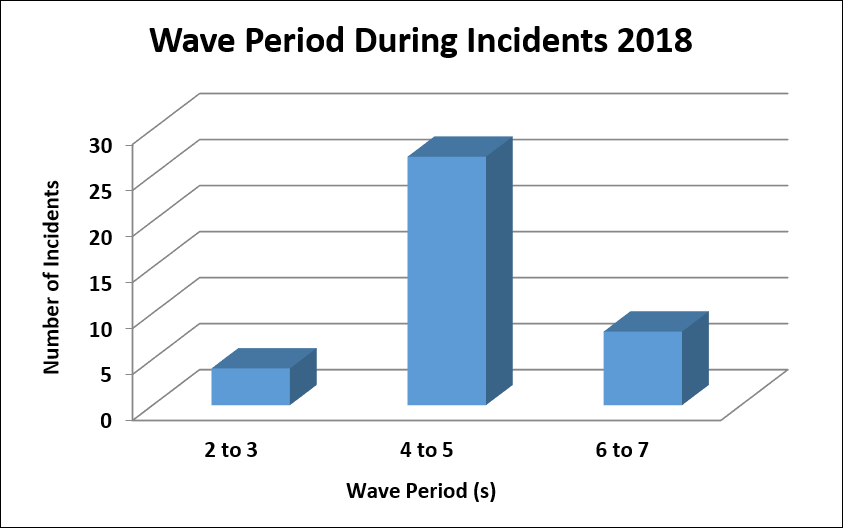

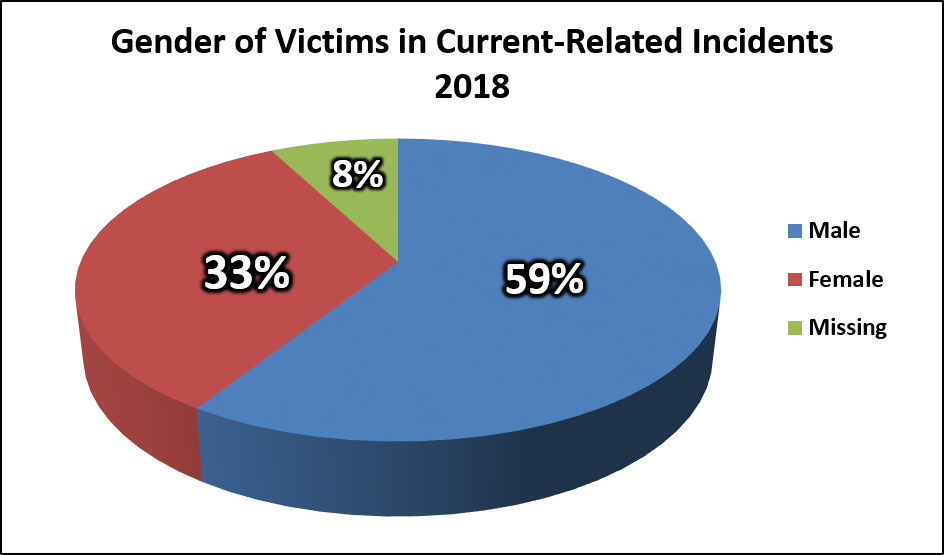

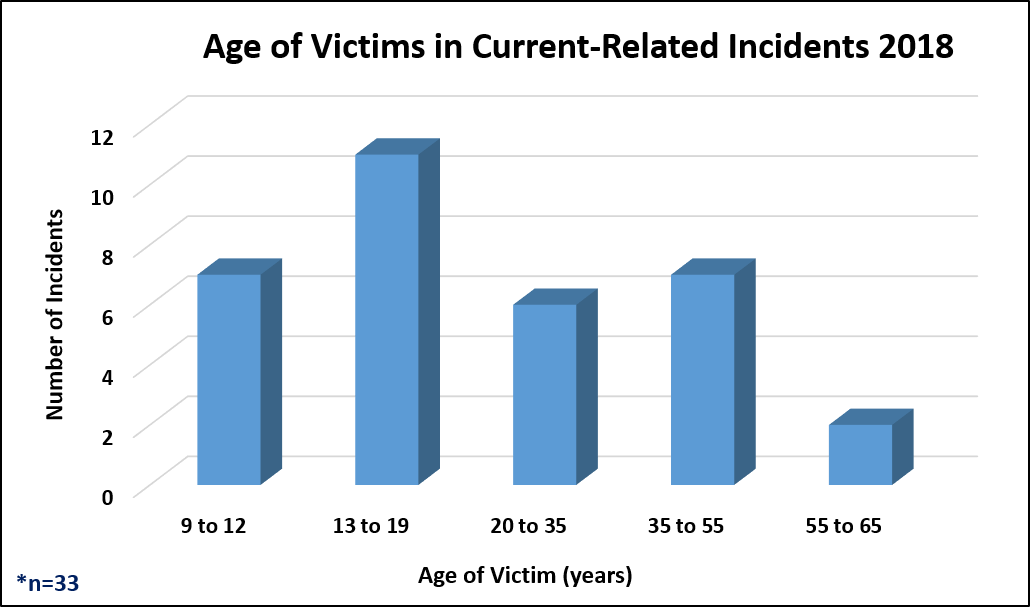

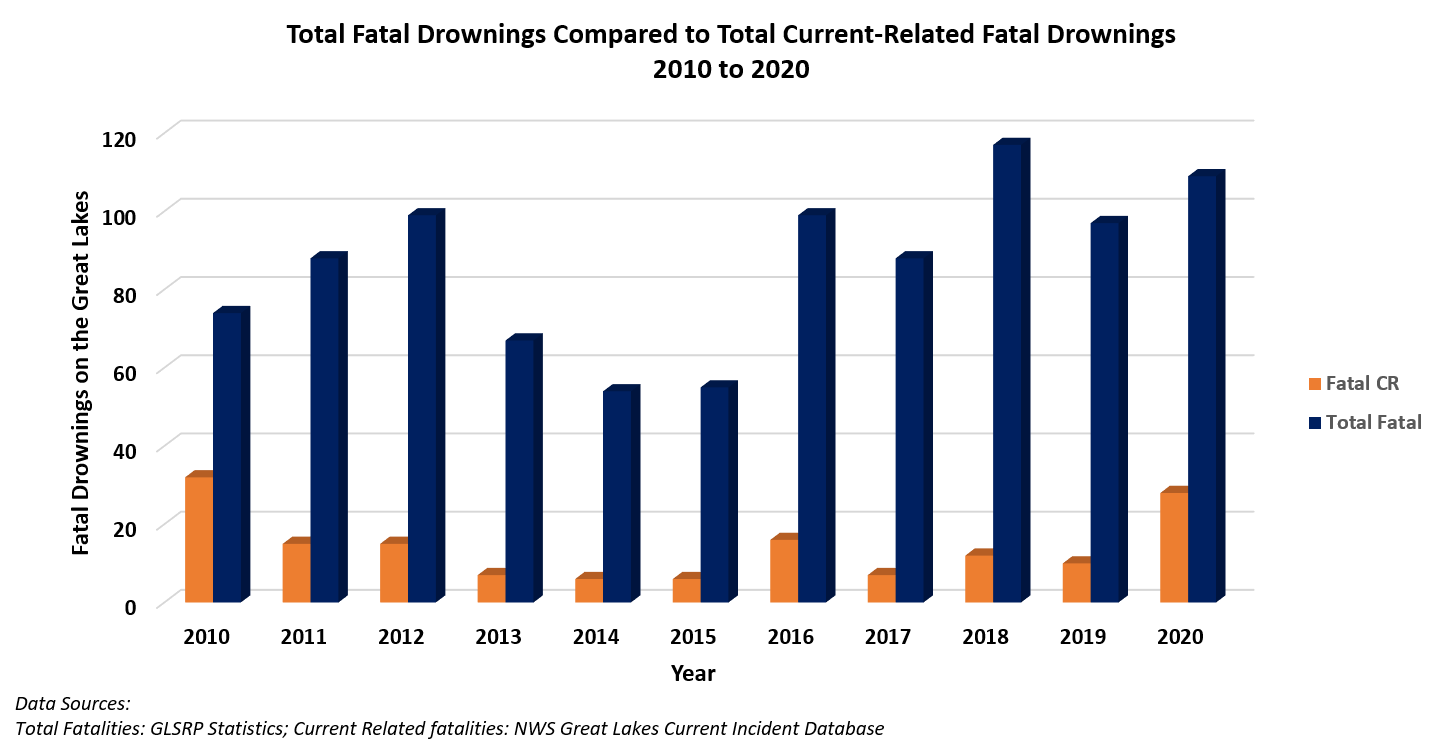

Overview

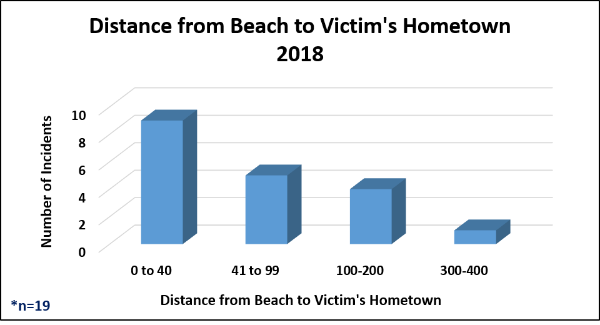

According to the Great Lakes Surf Rescue Project., 2018 was a record year for drowning on the Great Lakes, with 117 fatalities reported. Above normal air and water temperatures were likely contributors, drawing larger crowds to the beach. Despite this, the number of current-related fatalities ended up at the ten-year average of 12 fatalities, with a slightly above average number of rescues (27). A majority of the incidents (rescues and fatalities) occurred on Lake Michigan. Figure 1 shows the number of current-related incidents per year since the database began (2002).

Fig. 1. Current-related incidents from 2002-2018 (GLCID, 2018).

Air and Water Temperatures

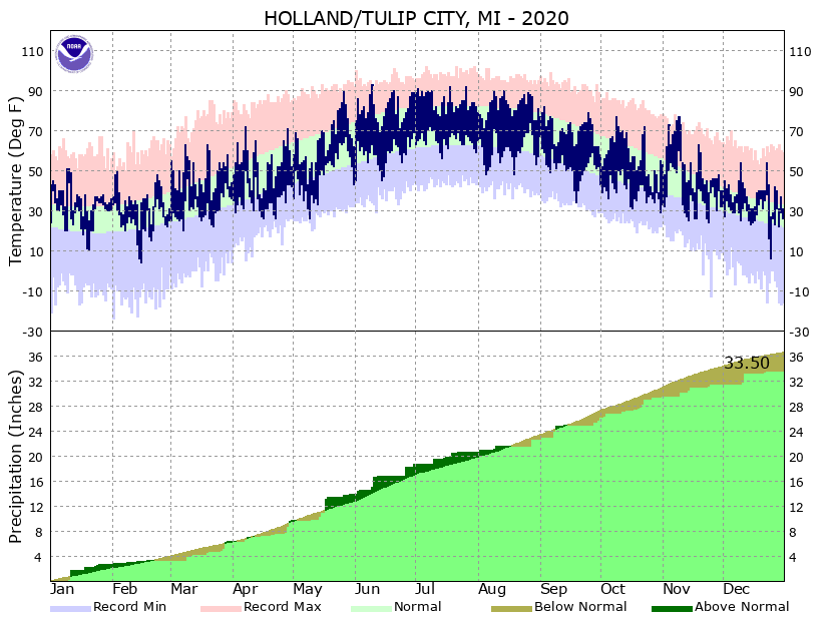

Air and water temperatures during the 2018 swim season (May-September) were above average, especially for the month of August. The above-average water temperatures (Fig. 2), in concert with above-average air temperatures (Fig. 3), likely contributed to the higher number of drownings in 2018 (117 fatalities altogether, 12 current-related). During the 2016 season we saw similar trends in air and water temperature, and that was also a record breaking year for fatal drownings (99 fatalities, 16 current related). Water temperatures this year remained near average until late June, just in time for the Independence Day Holiday weekend, and remained above until October. We had our first rash of current-related incidents between the dates of June 30th-July 6th, 2018. Daily temperature records were broken in several locations around Lake Michigan that week, with highs ranging from the mid to upper 80s to the 90s. The end of July began the stark rise to well-above average water temperatures, which continued into late August.

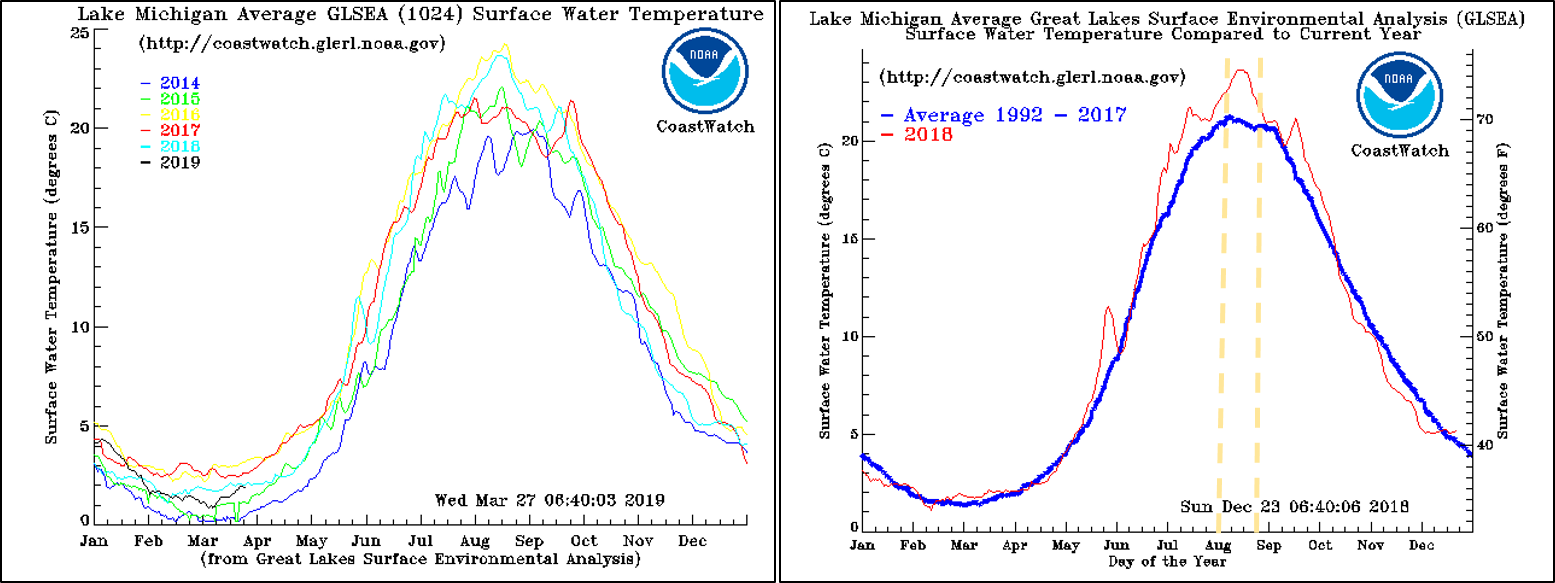

Fig. 2. Lake Michigan Water Temps (2014-2019 Yearly comparison on left, 2018 vs. 1992-2017 average on the right). Image from GLSEA.

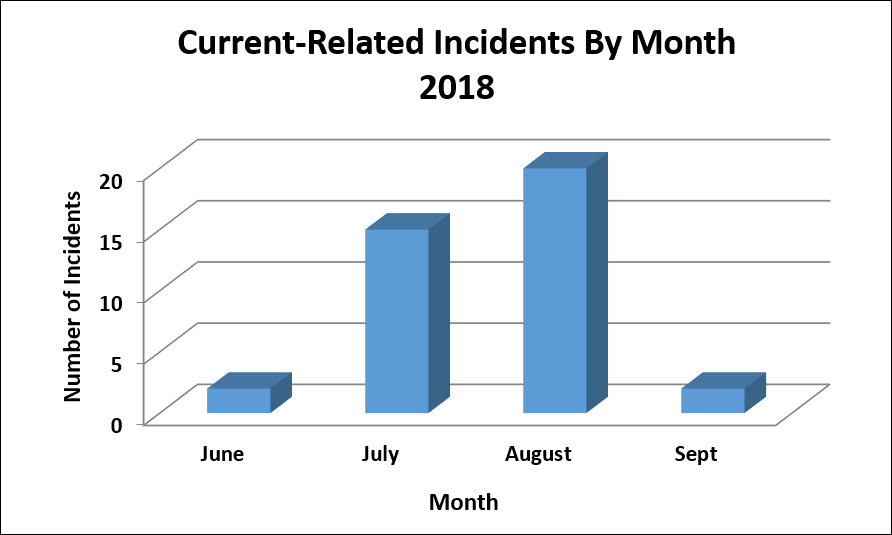

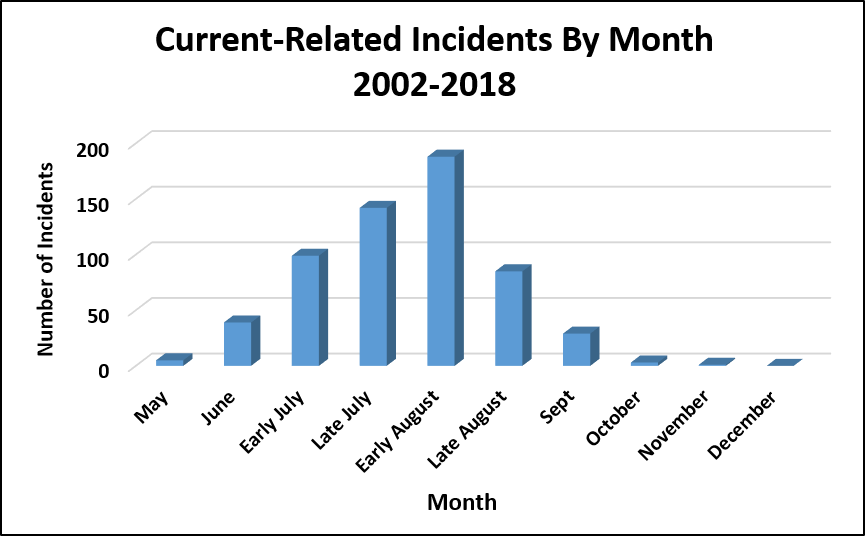

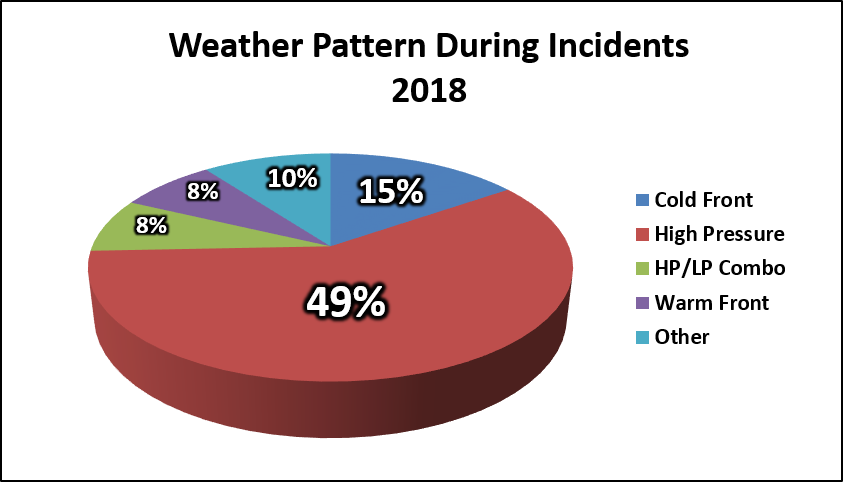

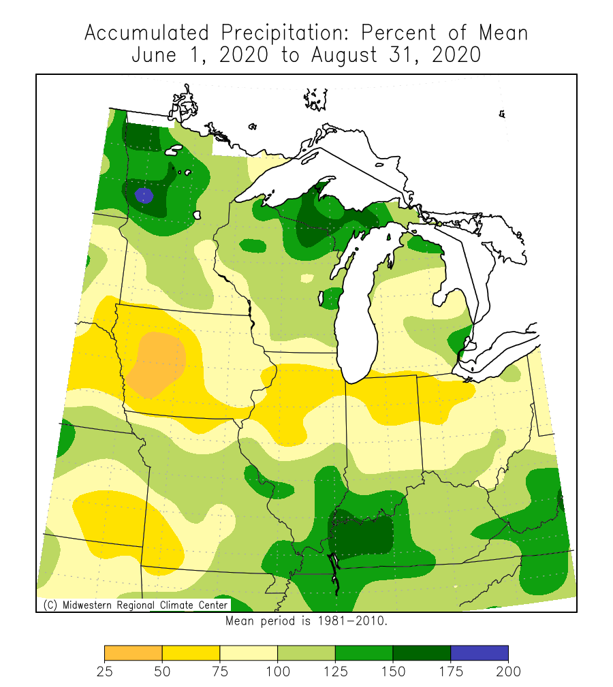

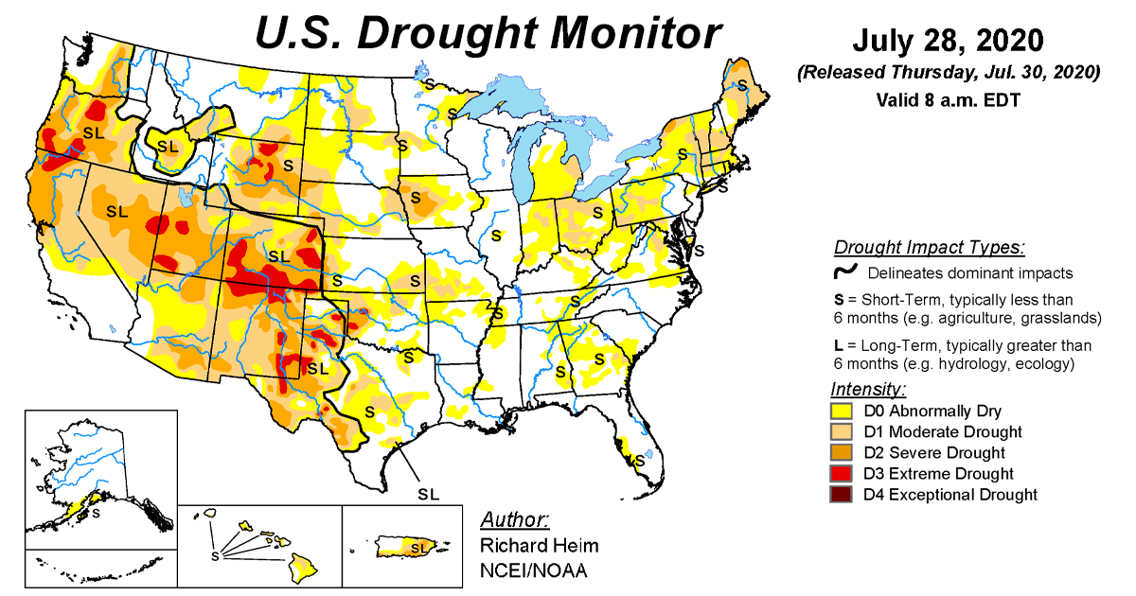

A majority of the 2018 incidents occurred in mid-late August(Fig. 4a), which is typical for the Great Lakes (Fig. 4b). From late July into August we generally see our warmest water and air temperatures of the year, and people are travelling for their final summer vacation before school begins. We can also get stronger cold fronts moving over the warm lake in August, creating instability and rapidly building waves. The quick increase in wave heights often catches swimmers off guard.

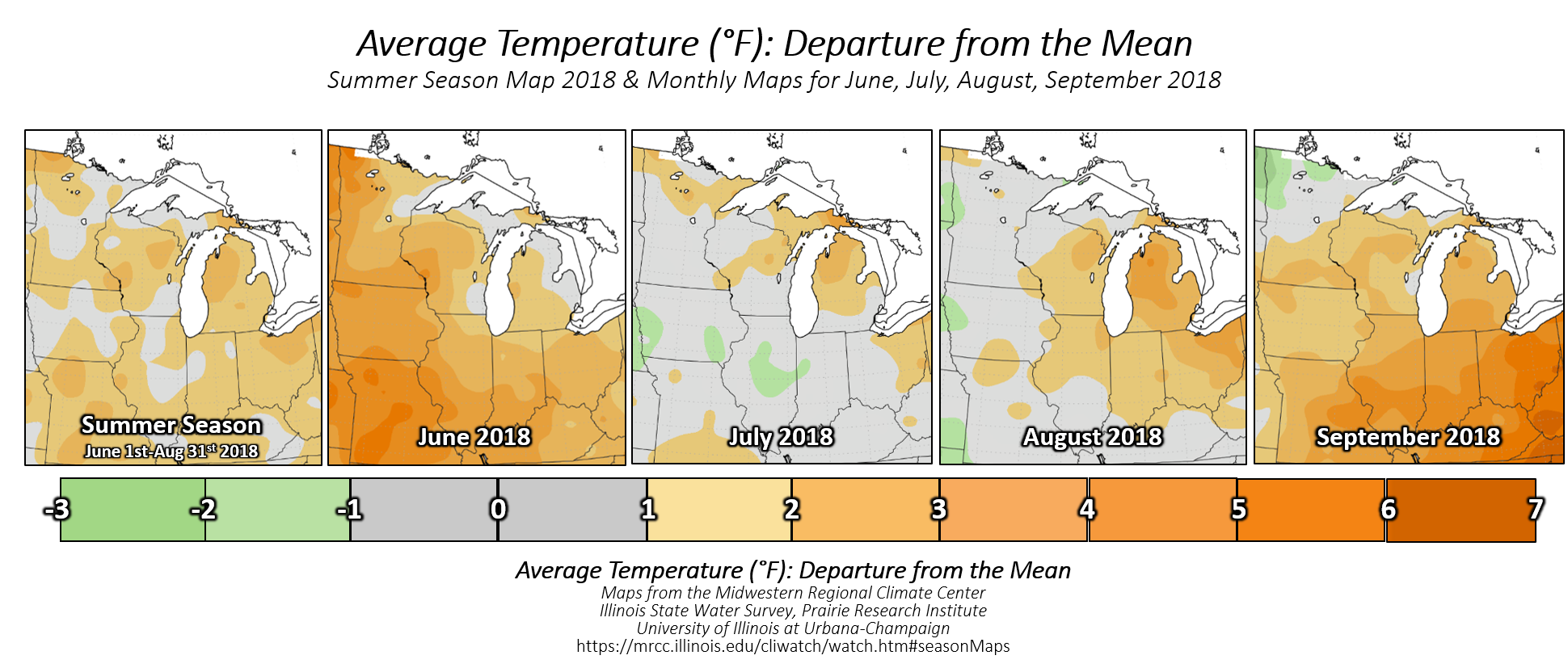

Fig. 3. Midwestern Regional Climate Center (MRCC). Average Temperature (F) Departure from the Mean for Summer 2018 (both seasonal and monthly maps).

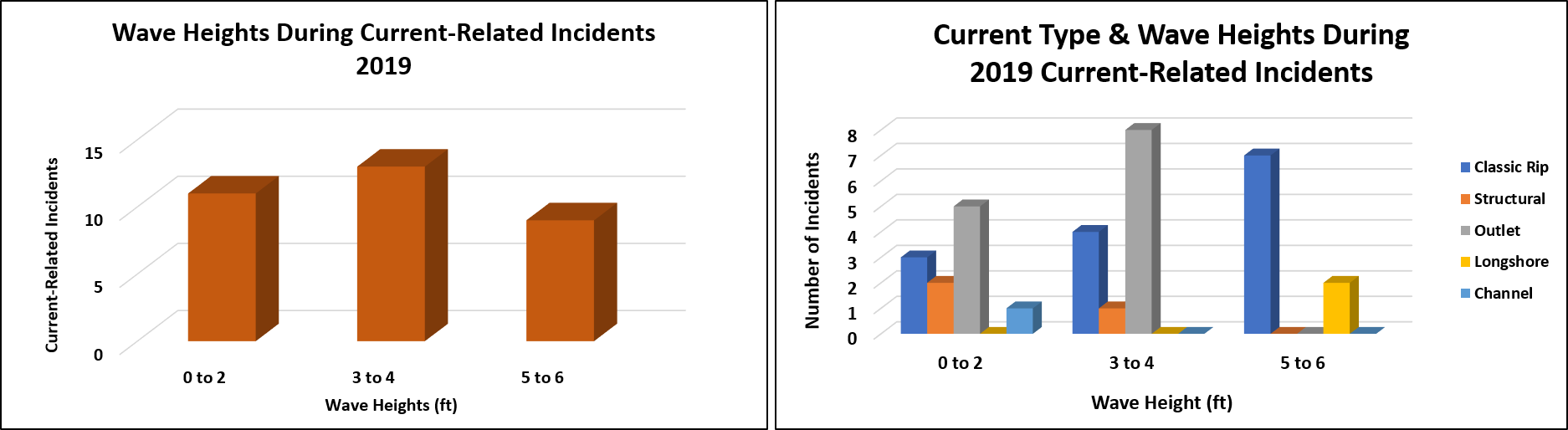

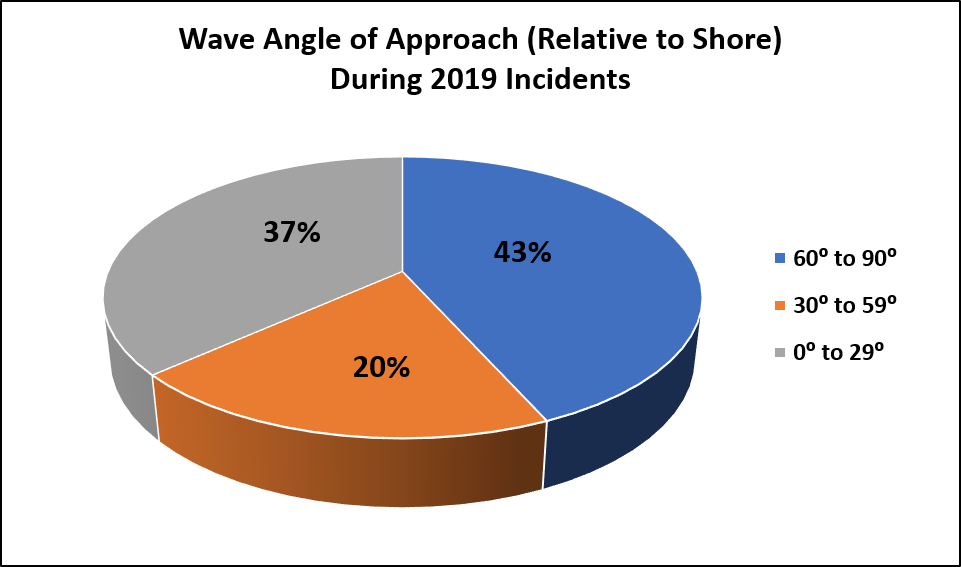

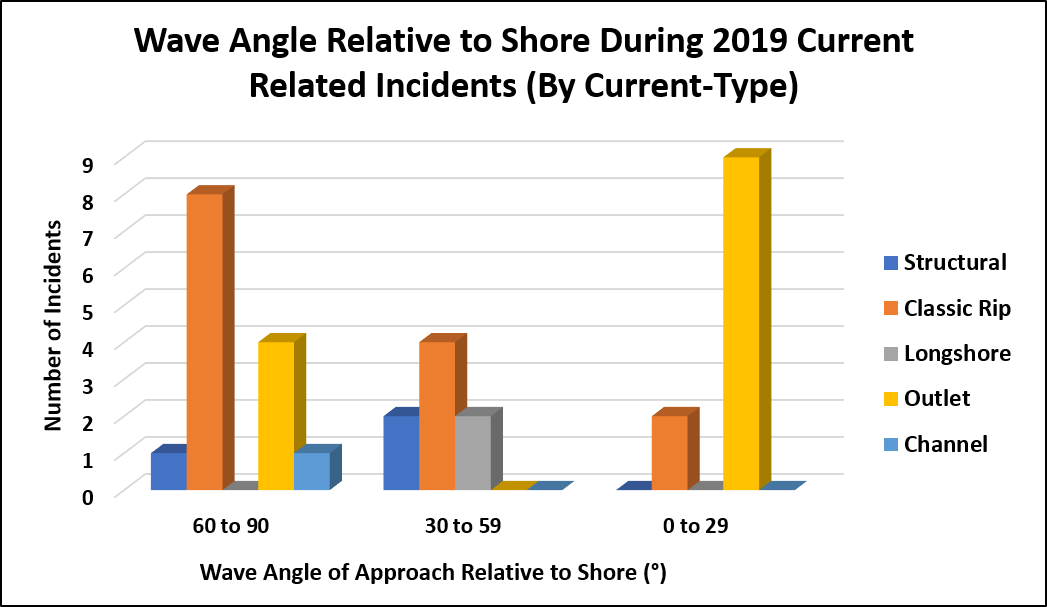

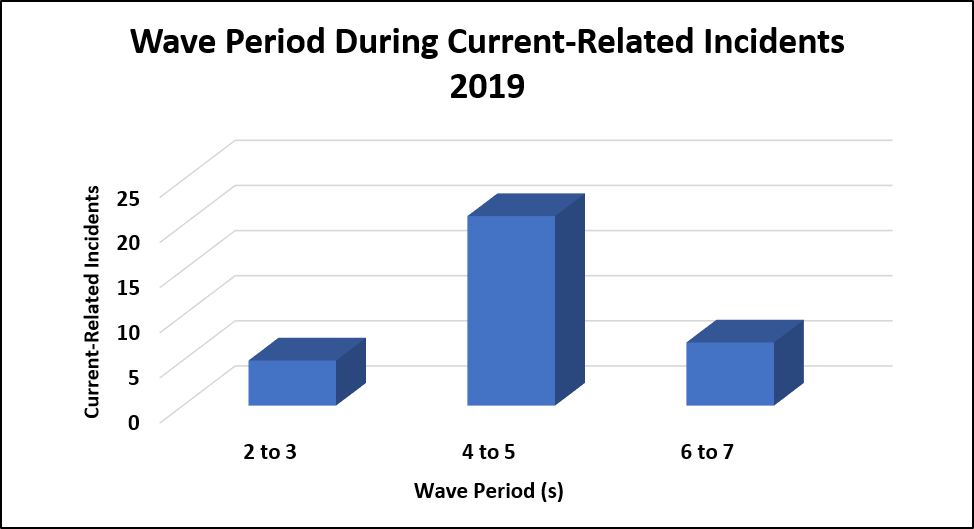

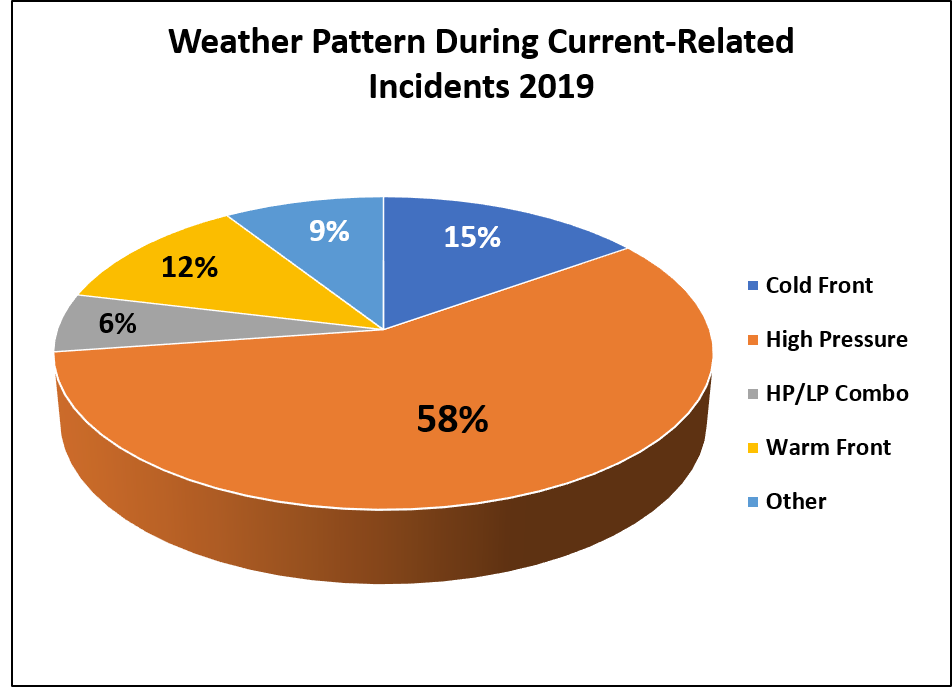

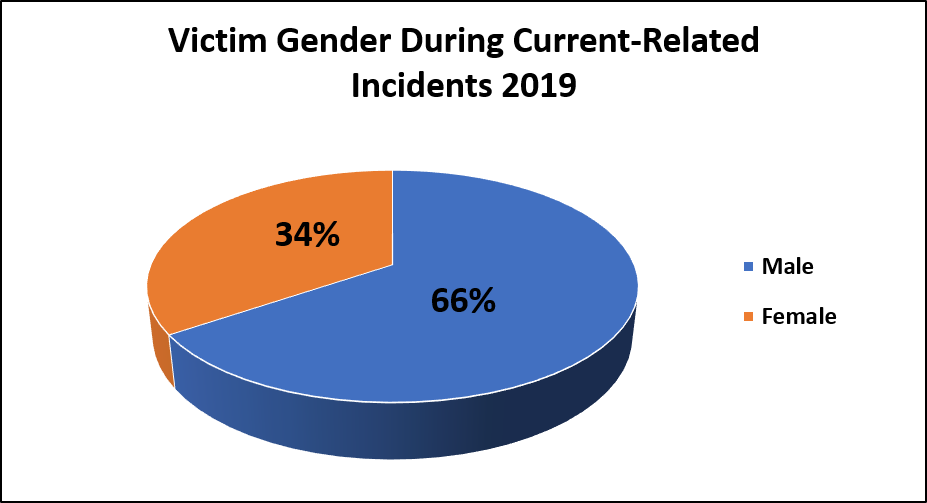

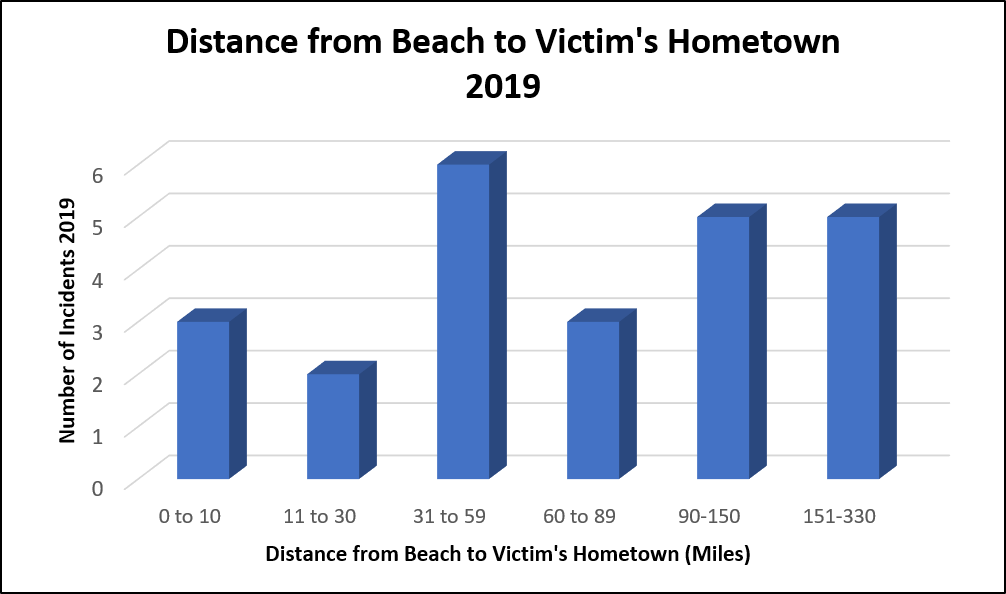

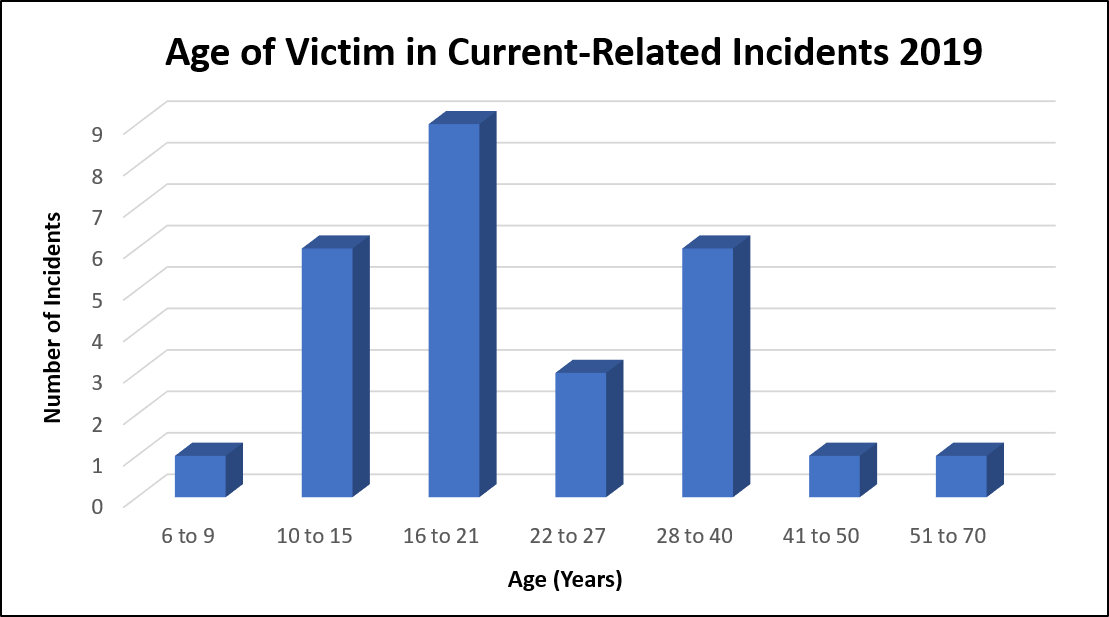

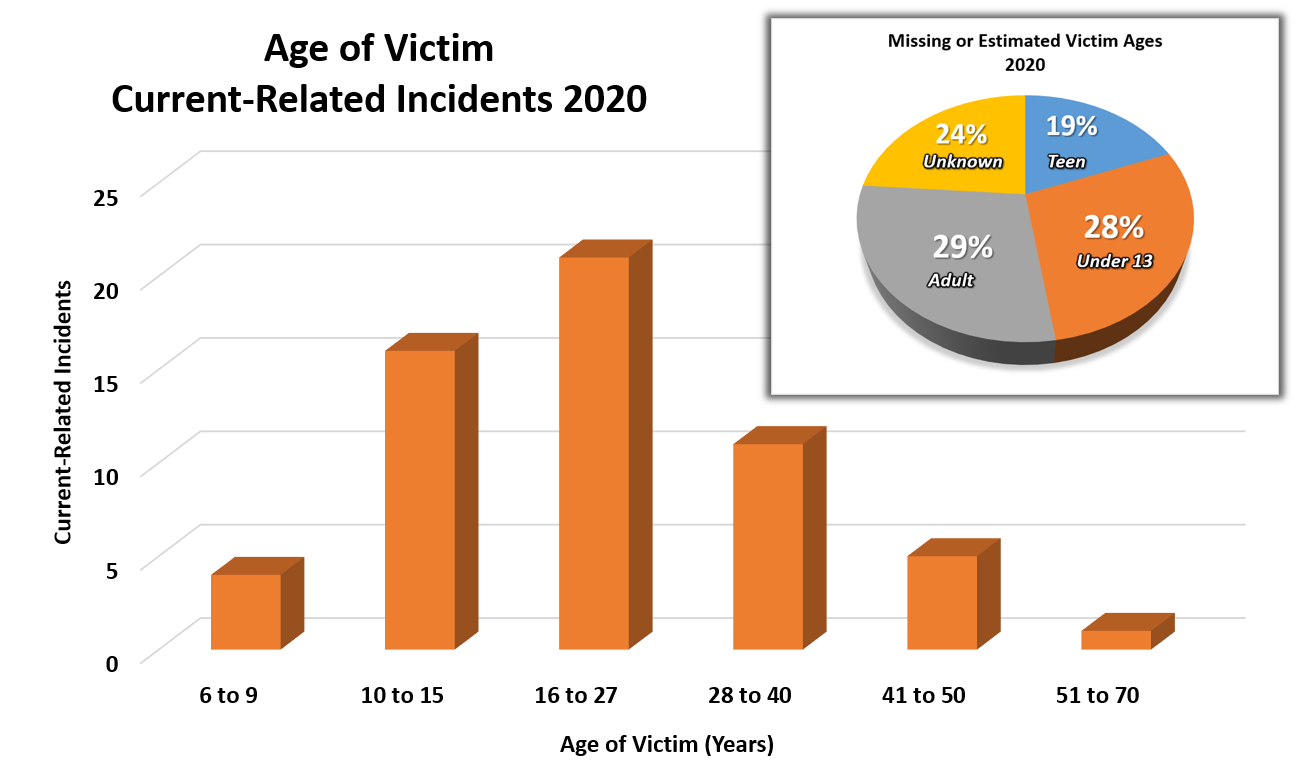

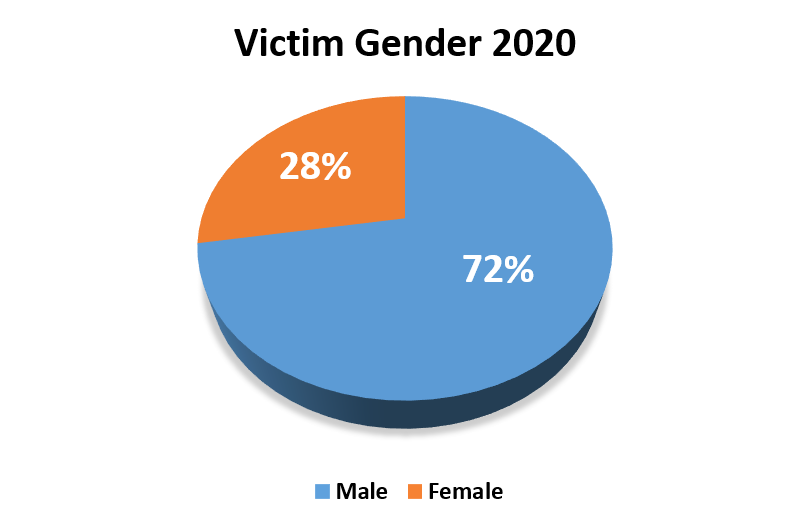

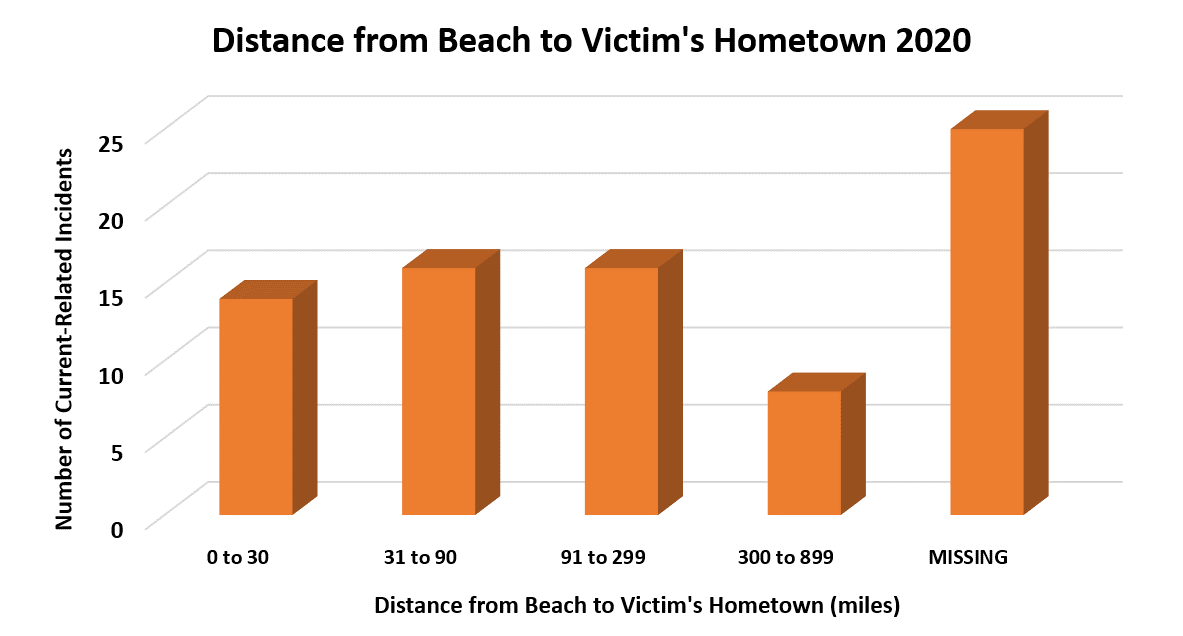

Fig. 4a. 2018 Current-Related Incidents by Month (GLCID, 2018).